Interview by Meritxell Rosell

Nature’s cycles of life and decay are fascinating subjects. And interruptions in these processes are even more intriguing. At a young age, I was quite obsessed with relics -mummification and embalming too, but relics had an added sense of esoteric mysticism. Not until more recently I came to know bog bodies, quite a frequent phenomenon in the damp Northern soils. These ideas of flesh in decomposition and biogeochemical cycles1, preservation and decay, life and death, religion and science have sparked my interest throughout the years.

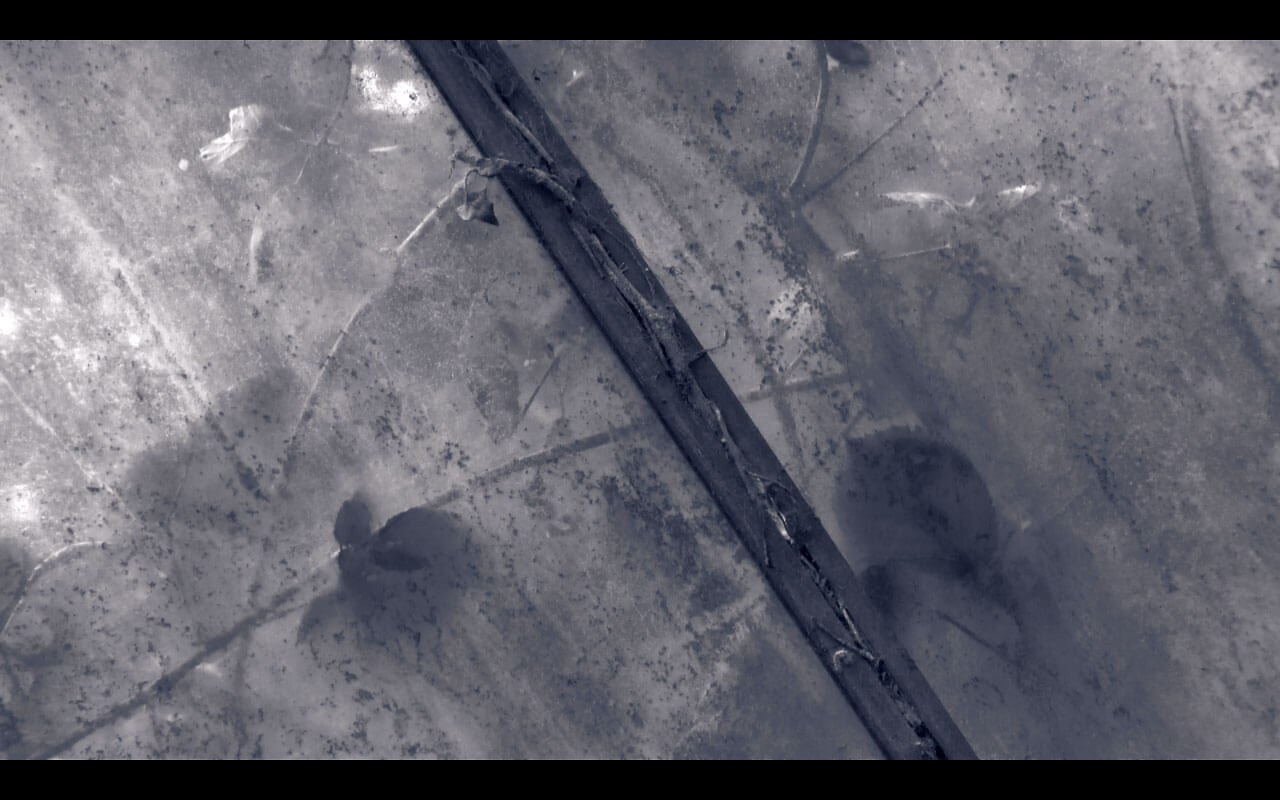

I was amused when finding out that Richard Skelton, an artist and musician from Lancashire in northern England, dedicated a whole album to the phenomena of bog bodies. In Belated Movements for an Unsanctioned Exhumation, August 1st, 1984 (2015), he wanted to draw attention to the rather inhumane way in which we treat ‘bog bodies’ by artificially preserving and exhibiting them. The process of exhumation interrupts a centuries-old, crushing embrace with the earth – a profound exchange through which the body becomes transformed and ultimately assimilated.

Skelton’s work feeds from the landscape and the natural world and, as he describes: evolves from sustained immersion in specific environments and deep, wide-ranging research incorporating toponymy and language, ecology and geology, folklore and myth. I would also add a reference to an emotional resonance with space and time.

Another of Skelton’s inspirations grounds in the work of Thomas Browne, the 17th century polymath who wrote several books reflecting his diverse studies including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric infused by a deep curiosity towards the natural world and influenced by the enlightenment’s scientific revolution. Skelton finds Browne’s work “poignant because it seems to represent that flawed and failed Enlightenment ideal of understanding nature through the application of universal laws. He makes the analogy of his own equally flawed enterprise – understanding nature through music” – to the point of naming several of his albums after some of Browne’s treatises (Garden of Cyrus, Nimrod is Lost in Orion) Osyris in the Doggestarre).

Skelton was at Unsound Krakow 2017 for their Flower Power edition. He presented his latest work, Towards A Frontier (2017), with one of his rare live performances and also a talk. He discussed with The Quietus editor Luke Turner the recurrent themes of his work – landscape, nature, life cycles and their connections with music, as well as a recent residency in Iceland which led to the work being premiered at Unsound.

This new work derives from Frontiers In Retreat, an ongoing 5-year residency which takes artists to travel to remote areas (Iceland in Skelton’s case) to research the history of the planet, the current ecological changes shaping the biosphere, as well as possible future speculative scenarios. Artists work across various epistemic frameworks, methods, and understandings of ‘ecology’. Skelton’s Towards A Frontier comes in the form of music, film and an accompanying book. He found the idea of the project intimidating, a bit of vertigo before opening to such intellectual vastness, but by the end of it successfully created a melancholic and profound piece of work.

1 In environmental sciences’, Biogeochemical cycles are the pathways by which a chemical substance “moves” through the “living” (biosphere) and “non-living”(lithosphere, atmosphere, and hydrosphere) compartments of Earth. Ecological systems have many biogeochemical cycles as a part of the system: the water cycle, the carbon cycle, the nitrogen cycle, etc. All chemical elements occurring in organisms are part of biogeochemical cycles. In addition to being a part of living organisms, these chemical elements also cycle through abiotic factors of ecosystems such as water (hydrosphere), land (lithosphere), and/or the air (atmosphere).

You are a musician and sound artist with interests in nature and landscape -which you incorporate into your compositions. How and when do these interests come about?

I always struggle with ‘how and when’ questions. There was no particular eureka moment or conceptual breakthrough. I can best liken it to osmosis. These have always been my interests, and my creative life has largely been concerned with how to combine them. Landscapes have always had a very strong effect on my imagination, and I can certainly thank my parents for instilling in me an interest in nature from a very young age.

You presented a new project at Unsound Festival, created in response to the wild mountain landscapes of East Iceland. Could you tell us about the intellectual process behind it?

At Unsound, I debuted a new piece of music, Towards A Frontier, written and recorded in the east of Iceland between 2014 and 2016. I visited there on some occasions while participating in Frontiers in Retreat, a residency programme that aimed to foster “multidisciplinary dialogue on ecological questions“. Naturally, the most pressing questions were those revolving around climate change, habitat loss, and species extinction, and these issues certainly cast a shadow over me, and my work, while in Iceland. I also produced some short films, including No Frontier, which obliquely addresses the environmental and cultural trauma associated with the ‘Anthropocene’, through images, music and found text.

How do landscape and nature impact your creativity? Is it something about their intrinsic patterns and rhythmicity, or is it more about how they get into our moods and feelings?

It isn’t something that is easily defined, observed, or related, but yes, I do often think about a landscape’s patterns and rhythms in musical terms. In the past, I used to make music en plein air because I believed that physically situating my musical instruments in the landscape would create a connection and that a kind of contagious magic would occur. More recently, I’ve been drawn to the idea of sympathetic magic, and I think of the vibration of a string that is resonating in sympathy with the hidden, inaudible music of the landscape.

You also run a small press (alongside Autumn Richardson), Corbel Stone Press. The press is a platform for music, art and writing informed by landscape and nature focusing on ecology, anthropology, folklore, animism and other-than-human consciousness. In times where our lives are being taken over by computers and algorithms, what do you think there’s to learn from the natural world that surrounds us?

I couldn’t hope to answer such a question briefly. The terrain is highly complex. It can certainly be said that there is a tendency in our highly technological, urbanised societies for us to become increasingly disconnected from the natural world. But equally, some might argue that computer technology such as streaming video helps bring us closer to species of which we might otherwise be unaware, or that social media is a vital tool in raising awareness about environmental issues, and in uniting people and maximising their lobbying power.

To answer your question, both Autumn and I believe that the natural world has a right to exist, and thrive, over and above any usefulness that it might have to humankind. Whether we can learn from it or not is not the issue. Our work is often simply about celebrating the unseen and the overlooked – to remind others that it exists and to help foster an appreciation of the natural world.

Considering Unsound’s theme for this edition, could you tell us what Flower Power mean to you?

Flower Power has a strong association with the non-violent protests of the Vietnam War era, which, in some ways, have echoes in the work at Unsound that focused on the plight of Poland’s Białowieska forest, Europe’s last ‘primaeval’ woodland. Both Autumn and myself are interested in, and involved with, the various movements that protest against environmental destruction and promote small community self-reliance through permaculture, seed saving and skill sharing. In our small way, we believe that the work we do through Corbel Stone Press contributes to this effort.

You couldn’t live without…

A little black notebook and pencil. I’d be lost without them.