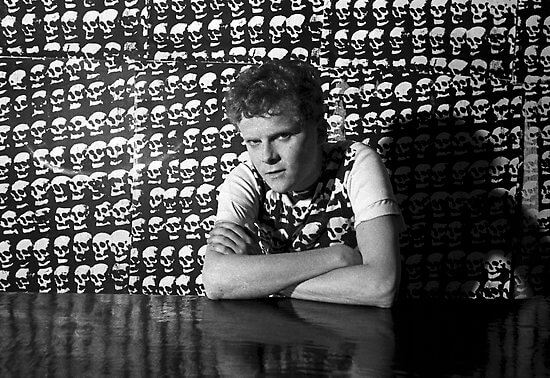

Words by Meritxell Rosell

Tom Ellard is a multi-faceted Australian musician, media artist and researcher. In his own words, he’s ‘made jingles, soundtracks, muzak, hit singles, noise installations, videos, interactive worlds, and many many failures’. Ellard is best known for founding Severed Heads, an electronic and industrial band that saw the light in 1979 and became an icon for industrial music.

The band went on to be one of the most creative groups of the 80s. Influenced by English and Australian punk bands, the artist has had an interest in media and technology since an early age; this brought him to explore music technology from computers to sequencers and synthesisers (he’s an avid collector of synthesisers too).

Ellard is continuously evolving his artistic practice. Apart from his musical career, he has a long history in media arts and, until very recently, he was a teacher and researcher in art and design at UNSW Australia. But music remains at the centre of his work, and music has been the articulating point of two of his most recent projects, which both bring a challenging and stimulating view of how we experience music.

In 2013, he created Hauntology House (HH), an online toy developed for Australia’s Adelaide Festival in association with ABC Arts. HH is an interactive game but a music album “where you walk around inside and operate some of the music yourself”.

In just a few days, he will be launching his newest creation at Unsound Krakow, Treasure Map 2, a virtual reality experience which deals with the theme of location/dislocation – in this particular case, islands to be explored. You can jump from different islands to get different pieces and versions of the album. Treasure Map 2 feels like the obvious next step in light of the artist’s interest in immersive 3D and virtual reality.

Heterotopia is a concept elaborated by the philosopher Michel Foucault that aims to define a social space of otherness. Utopias are ideal spaces that don’t exist, whereas heterotopias are spaces that simultaneously exist and do not exist but are based on an altered displaced reality. Foucault used the mirror as a metaphor for the duality of heterotopias, the reality and the unreality. The person we see in the mirror exists because the mirror is showing something that is real.

However, the image we see in the mirror itself is not a real person. It does not exist on its own. With video games, immersive experiences and virtual reality, we can create our own heterotopias and build our own places and spaces that we can experience while not physically being there. We can design our mindscapes and create worlds that are a reflection of our society but do not operate under the same parameters.

Tom Ellard is inventing alternative realities that are a reflection of his creative universe. We can’t wait to see and experience what’s on the other side.

You seem to have a long-time interest in new technologies and incorporating them into your artistic practices. Where does this interest come from?

Initially, it was the promise of a wider palette of creativity that ‘new media’ offered in the late 80s/early 90s. That promise didn’t pan out – it all became cheesy tech demos and navel-gazing that the ‘glitch’ movement finally denounced, which then led to reactionary analogue nostalgia. The hot air has moved on to robots and wearables and all that, leaving a realm where the digital.

flotsam of an old future is available. There’s a necessary balance between old and new – not the latest, not the quaintest – where the most spirit and humanity can be found. Both tape and CGI have to be used in the service of the idea – and that should be empathic, not robotic.

In 2013 you launched a video game, “Hauntology House”, and now you are presenting a virtual world, Treasure Map 2, exploring virtual reality. You regard both of these projects as music albums. What drove you to these expressions for your music? Could you tell us a bit about the intellectual process behind it?

The old saying is ‘architecture is frozen music’. But no one talks of architecture anymore – it’s ‘built environment’ now – places for people. I like to say – so where are the toilets? Then music is also liquid ‘built environment’, and an album should really be a living place.

A game engine gives you terrain, surround sound, emergent behaviours, and responsive features – all the good things you’d want for music in 2016. I’m not so interested in games, which should be something you can win. You can win and lose in Treasure Map, and you can die. But it’s mostly about finding music in places on a terrain.

Like ‘I found a good sound between two windmills on a hill’. It’s about people moving around a space and encountering a narrative, images, sounds, exerting effort, and me not knowing quite how they will do it.

Virtual Reality blurs the boundaries between the physical and the digital. How people respond to multiple stimuli in a digital environment beyond the touch of a screen or button is one of the questions to answer in this 21st century in which people live in a hyper-connected society. What impact do you predict for VR in a not-too-distant future?

VR is another thing that liberates sound. Most cinematic tools – cuts, zooms, reverses, etc. are gone. The audience might be looking in any direction – how do you guide them? Lighting, set design… and sound which is truly immersive, unlike vision which remains selective even in VR. I’m making VR videos to learn the craft, but long term, it seems a way to shake up the politics between vision and soundtrack.

Even with Facebook and Samsung in collaboration, the uptake of goggles is really not that great and probably not culturally significant. But the culture of surround audio is likely to spill into flat-screen movies – as it has in horror films where sound design already leads the imagery.

Interfaces will, at some point, step off the screen. Not sure how that’ll pan out. Siri and Cortona are clumsy, but goggles are more so. Earbuds are already way ahead of goggles, both technically and socially. Visualisation needs to make room for sonification.

Unsound’s theme this year is Dislocation, which can have very different meanings. What does Dislocation suggest to you?

They’re splitting things across a map, so the fragments are wider. I am more interested in the nowhere. Like the other day, I became ill and fainted (better now!), and the first thought on coming back was ‘Where am I?’ There was a moment of nowhere. A computer game will very often use the device of amnesia to allow you to build your own reality from scratch. Dislocation provides you with far greater potential than somewhere.

Probably also a nobody and able to create a character from scratch. So this dislocation and disappearance is an opportunity. I hope my game can convey that idea.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

I recently quit a paid job in the creative industry; the creative bit was OK, but attach the word industry to anything (music industry, fishing industry), and it’s dreadful for the subject of the term. The creative industry is bunk. It’s advertising plus woo. To actually create requires a set amount of uselessness. As in, “It doesn’t do anything – that’s the beauty of it”. Seems to me that later on, that useless thing will suddenly become very important…