Text by Agata Kik

We need a theatre that wakes up nerves and heart. These words today sound as contemporary as a century ago when Antonin Artaud advocated his Theatre of Cruelty. Artaud’s emphasis on the physicality of an artistic experience could not be more resolutely revived than in October 2018, when Christian Duka presented his yet unestablished curatorial practice in the form of the performance titled UR: Human Presence at Aures in Waterloo, London.

Collaborating with sound artist Jose Macabra on the sound design, Rebecca Evans and her Pell Ensemble on the body movement part, while having artist Elissavet Sfyri both physically and sonically perform live, together with Marco Maldarella as a visual illuminator of this complex multimedia event Duka turned this UK’s first fully immersive audio-visual environment of 50 speakers 3D sound system into a metaphorical body, a living organism with the electronic sound acting as a voice of a breathing machine.

Turning to the physical knowledge of osteopath Sundip Aujla, like Antonin Artaud in 20th century Paris, Duka created an ‘asphyxiating atmosphere’ to guarantee his audience the experience of ‘spiritual anarchy and intellectual disorder’ and let them, at least temporarily, lose touch with the tumorous tempo of the paroxysmal present-day. I believe in the contemporariness of the Theatre of Cruelty, as we still need something that would dominate the uncertainty of this unstable period of history we live in.

UR was a crowded, closed space with a limited capacity for the rather repressed public, with whom the artists shared the stage. The new way of performing has its roots in the XXth century’s refusal of the theatrical divide. However, with the electronic equipment, the artist’s embodiment of technology, and the immersiveness of art experiences these days, Artaud could only wish for it does not know its boundaries.

Freely sharing the floor with the artists, the viewer performed in the event just like he or she does on the everyday reality stage. In this way, everyone watched and was watched simultaneously, responding improvised to each other’s active energy. Nonetheless, two of the artists were situated above the rest of the participants.

Duka and Macabra, as the only sound artists in the event, shared a podium and had control over the whole happening. With every movement of their fingers in direct contact with the electronic machinery, the room’s energy, all the vibrating matter and immaterial emotional states were changing accordingly. The whole performance was designed to highlight the human body, and the source of the sound was its metaphorical brain.

Interoception, a sense of what is going on inside one’s body, was the main idea behind the performance structure that brought awareness to the dynamics of changing bodily states of internal balance and imbalance in return. In this way, the public coming from the outside could be equalled to images, sounds, taste, touch and smell that affect the body externally. In contrast, all the artists occupying the vast space inside Aures, filled with live sounds of Elissavet Sfyri’s amplified inner organs, acted as the internal bodily systems.

Sfyri’s cold naked body, concealed under moist latex fabric, like a mouth-watering wrinkled plastic skin, apart from the murmur of her stretching guts, resonated dry enigmatic words in Greek that came out through her amplified skin. While its content made no sense to me, language as pure form acted only as sound, affecting its vibratory intensity.

Like warm breath inside my ear, her whispers could not be more physically felt. In this way, the performance expanded the limits of language through the body and gave birth to this kind of non-verbal language, a vibratory phenomenon. Just like Artaud would envision in the Theatre of Cruelty, each participating artist in Duka‘s performance acted as an ‘animated hieroglyph’.

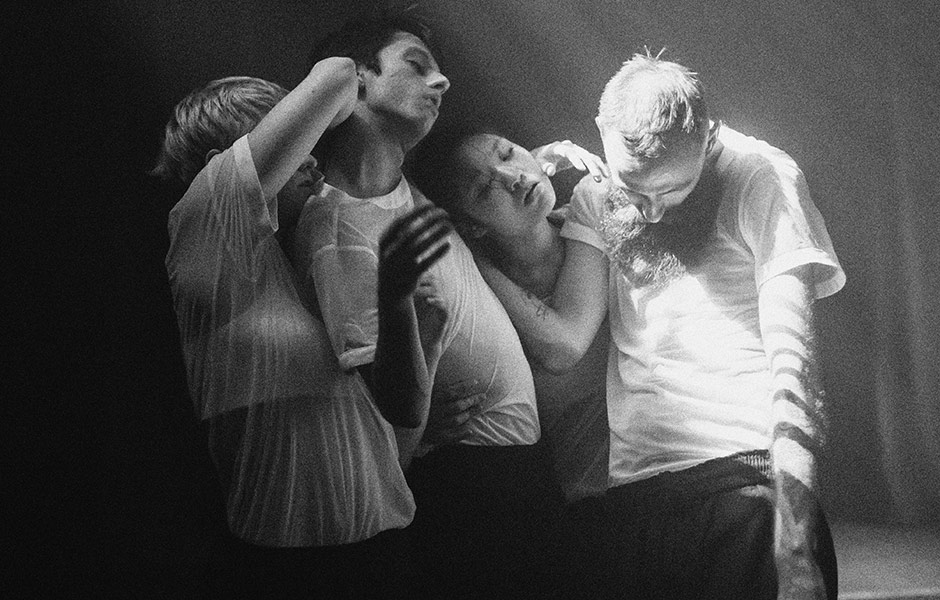

Apart from the sculptural nature of the 3D sound in the space, the performing bodies directly affected the public, targeting their sensuality by purely physical proximity. As a total spectacle, UR exhausted the idea of collectivity by mixing the freely moving bodies of the viewers with the movements of the Pell Ensemble dancers.

Dressed in white, these innocent-looking figures were consciously moving through the black space filled with dark beats. Their dead faces lured for an exchange of gazes, while their ghostly bodies, flashing under the lights, allured and repulsed congruously. Performers or the audience, whose presence it was, it did not matter; only the awareness of us being close together made the difference.

The physical closeness and extreme vibratory sensations of this extreme sonic environment were something that definitely made one become aware of their bodily presence and belonging to the three-dimensionality. Having said that, I cannot ignore that the affective power of sound encourages the consciousness to trip away and forget about the body’s materiality. Art is also a mental journey, so I would not limit human presence to 3D only.

UR was a fearfully emotive journey that took me through extreme embodied experiences from neurosis to ecstasy. Imagination, emotion and embodied memories are those experiences that let our presence extend outside this reality. Virtual and material presences might not necessitate hierarchy in the end. This is something that digital technology only ever-increasingly emphasises.

To straighten the body in balance, to rise up to effervescence, reach euphoria and to suddenly slip out of tune and fall into the monstrous darkness of the unconscious psyche. The whole performance developed through different states of balance and imbalance, feelings of welfare and desperate panic. At the start, while bright light was sparkling in unison with shimmering soft sounds, the audience was conscious of every other body.

Dancers improvised together with the members of the public scattered across the room, who physically responded in return. With the sound gradually darkening, the visitors slowly became shier and shier, backing up together to form a safe circle at the room’s edges. The dancers’ bodies, getting tighter together while sinking into each other’s flesh like a swarm of limbs, became one trembling organism in the centre of the spectacle. At the same time, the vertiginous voice coming from Sfyri’s viscera gradually became more and more violent, speeding up its drift around the speakers, coming from any side of the space at a dizzying rate.

I bet everyone present, not just me, was slowly becoming scared and stiff. With increasing confusion, I felt a blue sound stiffening my veins and, at the same time, excitement reddening my face. When the speed of sound reached its momentum, my inner battle was confronted with Elissavet tearing her plastic skin. With a pointless search for guidance, I was left breathless in this voluntary imprisonment. The trembling body of the artist was finally fully uncovered from its latex veil.

The epileptically flashing lights like a storm of flashbacks from the last night’s nightmare finally let these traumatic feelings be relieved, released, overcome, taken control of and turned into an enjoyable battle. Sound like a mechanic saw cutting the conscious thoughts into unintelligible or irretrievable images and finally felt liberating. Surrounded by crawling limbs like trembling cadavers, our dying bodies were finally resurrected. After the sonic storm came the silence, a moment of reflection, acceptance and a much-needed embrace of traumatic memories.

Ultimately, I submissively surrendered to the sound. I had no energy to fight anymore, even though completely exhausted emotionally. I felt a complete cleanse, rebirth, physical and mental purge. I gave in, in the end. After the performance ended, we all left the space like silent drops of tears flowing with the river of deaf resonance.

These changing stages of the performance could not be a more accurate experience of the chaotic reality. UR made one experience the extremes. It meant for me to simultaneously feel a caring caress and be heedlessly hurt. The cruelty lay at the core of affective power in the hands of the sound artists to influence the human psyche with such intensity. During the performance, I became an object tossed around the noise that was hard as nails. The disinterested violence of the performance could result in such a purifying outcome. Cruelty means intense unpredictability; we need instant shocks to revive our understanding.

This is why I think of Antonin Artaud now and the ways we return to his renewed exorcisms in the present day of contemporary digital technology. I am in no doubt that in the contemporary age, we need these electrically powered performances to leave these mental scars that will penetrate through the skin and express the secret truth of our immaterial energetic sphere.