Interview by Silvija Daniunaite

The creative horizon of media artist-slash-motion designer Maxim Zhestkov spans several disciplines from all across the artistic spectrum, combining art, music, architecture, design and computer graphics to create extraordinary digital landscapes that play with our perception of reality. Drawing you into a world that is both familiar and alien, each of Zhestkov’s art films displays a hypnotic ballet of colour, light, shapes and textures, echoing some of nature’s most divine phenomena while roaming the terra incognita of the future.

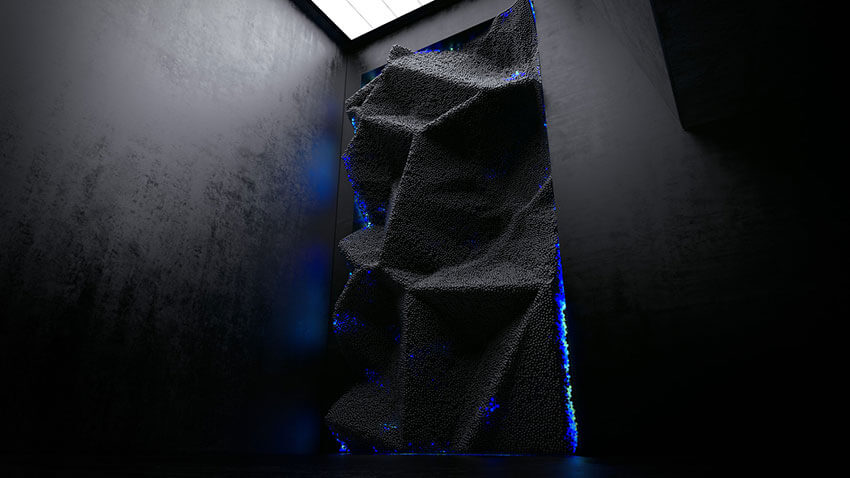

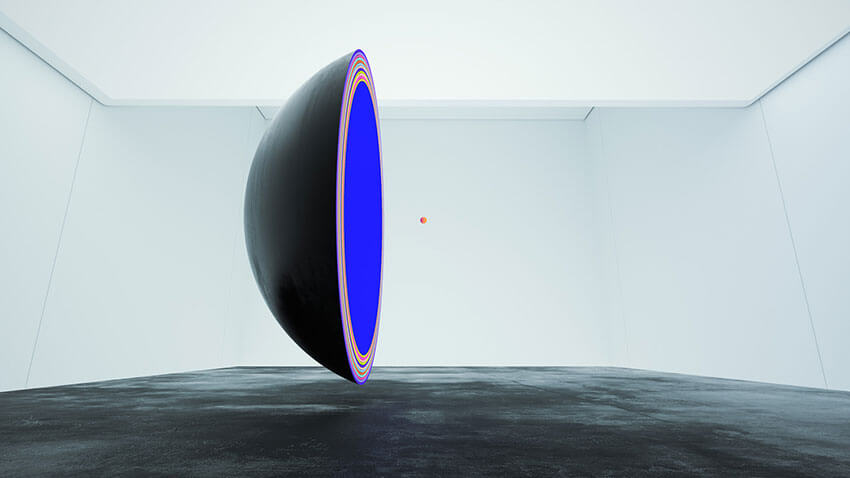

What can be traced throughout most of Zhestkov’s experimental art films is his undeniable interest in the movement of different digital elements that play and interact with their surroundings in an endless dance of reciprocity. In digitally rendered contemporary gallery-like settings, we witness a dazzling choreography of abstract masses, where uncanny digital forms swirl, burst and morph into one another with dizzying rapidity, simultaneously surrendering to and defying the laws of physics at the whim of an invisible force.

Over the years, Zhestkov has carved out a distinct visual aesthetic of his own, melting the organic and the artificial to open up new gateways for us to reconceptualise our perception of and connection to the wider universe. Quite fittingly, exploring the notions of ‘the invisible’ and ‘the unknown’ lies at the core of Zhestkov’s creative philosophy, reflecting his bid to rekindle humanity’s appreciation of this miraculous world we all call home.

In its majestic totality, Zhestkov’s oeuvre seeks to explore the growing influence of digital media on shifting the boundaries of visual language while simultaneously questioning the traditional white cube gallery environment and our experience of art in the era of the digital. In addition to Zhestkov.Studio, a digital art and design studio, which encompasses all of Zhestkov’s creative endeavours, the ground-breaking artist also manages his commercial platform Media.Work, collaborating with the likes of adidas, Adobe and Google, among other global brands.

Currently on Zhestkov’s horizon is a plan to build his third creative studio, where, with the help of engineers and scientists, his lauded digital simulations could bleed into the real world, mutating into forever new forms and shapes in a series of real-life spatial installations.

One of his most recent projects – Temperature – will be the first one to step outside of the digital world, visualizing invisible temperature fluctuations via heat air flows. Escaping any pre-existing structures and classifications, Zhestkov’s video work is an enchanting odyssey through otherworldly terrains, where possibilities are endless, and imagination reigns free.

Your work often juxtaposes natural phenomena with technology, graphic design and architecture, merging the organic with the artificial. Could you tell us a bit more about your creative philosophy and the idea behind such a multi-disciplinary approach?

I started my journey when I was a teen. I was fascinated by art and architecture. I really wanted to create, and the worst thing for me was thinking about boundaries. At first, I thought that architecture and interior design could bring some really broad ways for experimentation. And when I started studying architecture, the first couple of years were extremely creative, where you could just dive into abstract compositions and build abstract forms, work with sculpture and small spaces.

Then, I realised that in architecture, there are too many restrictions on reality. With computer graphics (CG), I got this feeling that I have extreme freedom to express whatever I want and that I can work with this idea of truth. It has something really universal, which you can find everywhere, from the pattern of your retina to superclusters in the universe. It’s somehow connected with nature, with currents, flows and magnetic fields. I was fascinated by this ability to experiment with different approaches and decided to step deep into CG.

What I found was that animation is some kind of pinnacle of creative voices because it’s like a hub where everything connects, and you can work on really different layers of creativity. It brings some kind of true freedom to your expression.

My first experiments and ideas were really simple and concentrated mostly on copying nature – I just used spheres to understand how we can add weight to make things move organically. I was obsessed with cinematography, adding techniques from great cinematographers like Roger Deakins, and seeing how you can shoot abstractions in CG. Then, I got into computer simulations based entirely on math.

With Houdini, a 3D animation software, you could create your own environments with the laws of physics and make massive systems inside the universe that you built. It all comes from the core concepts of our universe, and probably all my work is some kind of an attempt to decipher the laws of physics in different ways. I really love to use spheres as the main character in my projects because we are all made from small particles and live in these big spheres.

For me, it’s really moving to understand that I’m talking to you at the moment, and everything around us is made from particles which create some kind of bigger structures, elements and materials. [My team and I] spent a couple of years playing with digital simulations, but in the end, it became clear that we are trying to mimic nature.

You are currently working on one of your latest projects – Temperature (2019). What was the intellectual process behind it, and how does it fit into your wider body of work?

Temperature is a project which will be the first one to step outside of the digital world. We bought chemicals which change colour depending on the temperature. It’s something like powder – you use this pigment mixed with oil, and it makes paint. You can then paint spheres with these colours and create really crazy animations, in reality, using heaters and fans with high temperature.

What I really love is showing how nature works, especially the process that we can’t see. We can see this phenomenon when we stand close to the glass, for example. Our breath forms interesting patterns. We can see it when we touch something hot or cold. We can probably use this idea as a reference point – just small pieces of visual representation of temperature, as well as different ways of thinking about these differences.

We are talking with specialists on global warming, and it’s pretty interesting how we can visualize these processes, in reality, to show people how it works on a really small scale. Temperature was on my mind for a couple of years, and I decided to finally start working on the project because we now have this capacity to do this thing with the reverse engineering approach. That is, we are trying different ideas in computers and then trying to implement them in reality.

How can we boil water and see elements change colour? How can we use wind, or electromagnetism, to change colour with temperature? It’s really interesting to find these tools and to be really close to nature because these processes are here every second, but we can’t see or perceive them with a simple glance.

Exploring notions of ‘the invisible’ and ‘the unknown’ seem to be at the core of your creative philosophy. What is it that draws you to this idea of making the invisible visible, of extracting things that we can’t observe with the naked eye? And what do you want the public to take away from such an approach?

I suppose art, for me, is a really intimate process of making something that could resonate on different levels. The language of nature is universal. We don’t have to use words to show our emotions via this language. It has no boundaries, no countries, and no nationalities. It’s for everyone – we all know what water is, no matter how we name the substance.

The same goes for temperature, light and other forms of nature. It’s crazy to [come to this realization] that there is a huge number of things around that we can’t see, and so we just take it for granted. It’s ‘okay’ for us to see patterns of wind on a pond; it’s ‘okay’ to see how magnetic fields form crazy patterns.

Probably the main idea behind every project that I’m working on is that we are taking for granted really big and fantastic things, like water transforming itself into crystal structures…It’s crazy! I’m trying to develop this inner muscle to start every day with a new perception of reality. My projects are based on the idea that we should take a closer look into ourselves and these beautiful processes outside – processes we can’t always see but which we are all part of. My work is an attempt to feel nature as if you saw it for the first time.

One of the criticisms pertaining to technologically driven art is that, while visually stunning, it often feels empty. You, however, have previously emphasized the importance of emotion in your work. How do you understand these seemingly contradictory worlds of technology and emotion, and how do you balance them out creatively?

I don’t think that technology could be a barrier to emotion. I love to think about CG as a tool. For example, in sculpture, we can say that a spoon we use to form something is in itself unemotional. But, with this unemotional piece of metal, we can form something that is a result of our thoughts. You are probably right about this idea of an unemotional approach in digital environments because a huge number of people can start experimenting really easily, without any thought process, without deeper explorations contained within.

This approach somehow devalues the idea of CG. But I don’t think that tools should be the final frontier for an artist. For me, computer graphics is just source code for our nature. We can tweak it, get an impression, make something interesting and watch it form as if it were a living organism. It’s really touching because, somehow, using this technology which is used in biology to open and decipher DNA structures, we can see how everyone was made. No matter if it’s an elephant, a mouse or a human – they are just the same blocks of information.

I’m not talking at the moment about CG in general. We are talking about parametric design and complicated simulations rather than just simply playing with geometry. In parametric design, we can find these tools which our universe uses to create things. I feel something really true in these processes because I can step away and become a witness to this beauty of forms and motion.

You work with computer-generated digital forms and sculptures. For our readers, who are less familiar with the intricacies of computer graphics, could you walk us through the technical steps of how a conceptual idea develops into one of your art films?

The basic process contains a couple of steps. In the perfect world, the first step is just to sit and think really deeply about what you really want to make. The second step is to then make digital particles with a computer and to introduce some boundaries and restrictions. For example, you make a virtual box and say that in this virtual box there are one billion particles. You hit play and these particles just lay there like liquid on the bottom of this box.

Then you think, what if I make these particles from some really crazy material, where every particle would stick to the others to become this glue-like mass? The next step would then be to introduce a force. It could be digital wind, for example; it’s like a small fan which uses pressure to transform these particles. You see these flying particles, but everything looks messy.

Then you start thinking that you probably have too many particles. What if we can instead use 1000 particles and make them big spheres? You re-simulate and use the wind again, but nothing happens because they are now too heavy. You switch it up a little and make them really sticky and less heavy. You then see that you can start forming some really crazy patterns inside this box.

What if we can use this matter as a sphere with 1000 small particles, and what if we can blow with this digital wind from two different sides? You play and see this crazy flower-like shape appear. What if we can add some material which would start glowing when the wind is just starting to move the particles? In two seconds, our particle becomes shaped like a coral. These processes are simulations.

I suppose real scientists use the same approach – they use some kind of boundaries, atoms, and molecules, and they use something to test these different environments. The next step would be the rendering. We build some architectural spaces, like a white gallery space, and see how it works with light. Then we start using digital cinematography – I become a guy with a digital camera on my shoulder, playing with different angles. Then we edit. And the final step is making the sound.

Since I’m really into sound, I make almost all of the soundtracks myself. It’s part of my artistic journey. The films work on so many levels – it’s an installation, it’s ideation, thinking, it’s making these simulations, where you’re a scientist, it’s being a light designer, a cinematographer, a sound designer. And the result is this one piece in digital reality. It’s some kind of post-truth world because you make art, which is only in the imagination and perception, rather than in real places.

As a media artist, you continuously seek to shift and push the boundaries of visual language, creating landscapes that play with our perception of reality. Speaking of your creative process, do your projects generally involve a lot of conceptual development beforehand or do they stem from a certain aesthetic need?

It’s always hard to know what the main hero in the project should be. The concept is extremely important, but developing and moving the concept to new directions can sometimes be more important than the first idea. It’s about duality. It’s almost like our brain – we have two parts which are in constant communication with each other. One is about logical ideas, and the other – is about expressions and free flow. It’s always about thinking and thinking back, going to the idea, switching to the concept again, and playing with visuals [along the way]. It’s a really great partnership. It’s really hard to say that one or the other is more important.

We live in a media-saturated world, and the rising influence of digital media is nowadays undeniable. As a media artist, what would you say has this rise of the digital brought to the arts landscape?

For me, it’s all about boundaries. In the digital world, we have too many possibilities. It could be dangerous. The best thing that artists could develop nowadays is to create self-awareness and the ability to build these boundaries. Without these boundaries, you feel really uncomfortable. It’s too many places to go to, too many directions to follow.

You have to create a really small ‘room’, and within these boundaries, you can then feel freedom. Think about the negative rather than the positive – what should we eliminate and what should we keep? And we should probably say no 99% of the times, and yes to only 1%.

Digital is everywhere and it has some sort of negative vibe inside of itself. It’s probably not a good idea to tell someone that they are a digital artist. I prefer to call myself a sculptor or a designer because the term digital art is pretty negative. The digital world is very big at the moment, but good people with high-quality projects are really scarce.

What I really love is that in a couple of years, a new generation of artists will come around, who will not only use these tools to enjoy them but will have a statement behind their projects. Where computers will just be instruments for their ideas, not the main character. This could change everything. I’m really looking forward to seeing how they will build this new reality.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Meetings and conference calls. I’m trying to manage my commercial studio and my art studio, and this stuff takes a huge amount of time. The best thing is to dive deep into the flow.

You couldn’t live without…

Meditations – in the broad sense that we live in a really fast world, and this ability to step away and to think about everything is really vital. I can’t live without this small piece of time where I can switch off everything and dive into some endless ocean of dreams.