Text by CLOT Magazine

A few renowned artists such as Nam June Paik, La Monte Young, George Brecht and Joseph Beuys are quickly associated with Fluxus, the radical experimental art movement founded by George Maciunas that profoundly impacted the art world during the 60s. Their vision of live performative art, the importance of the creative process rather than the final object, the sense of community and the role of art in society while incorporating radical new media changed entire generations of artists and their approach to their practice up to these days.

A maybe lesser-known name is Henning Christiansen, a composer and a visual artist, who was a central figure of the Danish branch of Fluxus and a close collaborator of other Fluxus members such as Joseph Beuys, Wolf Vostell and dozens of other artists. Despite his prolific avant-garde career and belonging to one of the central art movements of the second half of the 20th century, Christiansen’s oeuvre it’s not easy to get ahold of due to the scarce documentation and recordings available and the fact that his works are rarely performed. But early this year, two of Christiansen’s tape works from the 1980s, Peter der Große op. 174 (1986) and Gudbrandsdal op. 178 (1987), were released for the first time by the Institute for Danish Sound Archaeology, an independent association with the overall purpose of uncovering and releasing historical Danish electronic music and sound art, which already had published a couple of releases in 2018 with compositions of the musician.

It was during the 1960s when Christiansen became best known for his involvement with Fluxus, his tape music and minimalist compositions. At the same time, the 1980s represented one of Christiansen’s most prolific periods in which he composed some of his very best tape works. It is from this period the last two releases by The Institute for Danish Sound Archaeology belong to.

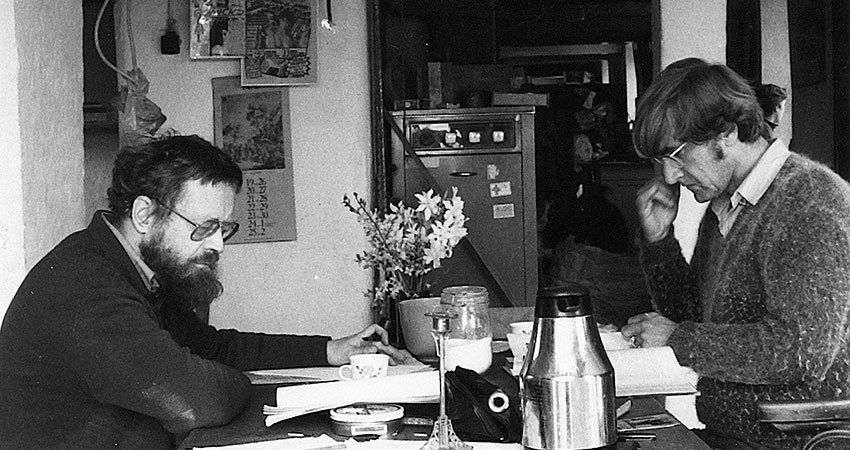

Christiansen’s career, one could say, was a series of turnings back and forwarded with a constant reexamination of his practice and the meaning of his art. With a classical music education, Christiansen took a first sharp turn towards the experimental art scene in the sixties and got involved with Fluxus and the Danish Experimental Art School Eks-Skolen. During that time, Christiansen became a central collaborator for Beuys (from 1964 until 1971 roughly) and created sounds for at least eight of Beuys’s actions using multiple tape machines, often participating on stage and frequently too playing back mixes of his own compositions as well as recordings made specifically for the actions. These recordings range from voice recordings, including Christiansen’s reading of poetry and texts to excerpts of radio broadcastings or even Shakespeare’s’ plays.

Experimenting with tape brought about two aspects that played an essential role in Christiansen’s work together with Beuys – recording and systems: the fact that sound could be taken from its acoustic context and inserted into new ones, that notes are preserved on tape, made repeatable and transportable in a medium that can be physically manipulated into a new system of expression.

Earlier in the forties and start of the fifties, Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry had already started using magnetic tape for recording documentary sounds and processing them up to becoming unrecognisable from their original source. What attracted these composers to tape, apart from its malleability, was this capacity for repetition, especially by forming tape loops in which the machine would play a given section of tape over and over without interruption. Such repetition made possible the close study of sounds that one would usually associate with a frozen visual image or the notation of specific pitches in a musical score. The work of these two pioneers started a long tradition of using tape in experimental music and sound art, in which Christiansen is included.

After the intense Fluxus period, Christiansen turned his back on almost everything Fluxus and went to create a completely different type of music. Instead of performances and minimal, conceptually-based art and music, he began composing in a neo-romantic style with classical forms like waltzes, symphonies and compositions in the Danish song tradition. He also recalled the music of Erik Satie and the Danish composer Carl Nielsen. Running away from the Copenhagen experimental art scene, his vision in this period had a social and political angle, composing scores for films, unapologetically Communist songs and some works for television.

But the eighties saw Christiansen turn again to go back to the artistic strategies he had left in the late sixties with a renewed commitment to his own vision of Fluxus. Peter der Große op. 174 was the score for a German radio feature and Gudbrandsdalop. 178 was written for a performance in collaboration with Joseph Beuys and later Bjørn Nørgaard. The two works stand out in Christiansen’s extensive and many-faceted oeuvre by employing almost entirely electronic sounds. While Peter der Große involves electronic instruments like synthesisers and a crackle box, Gudbrandsdal employs a more minimal approach and aesthetics through the heavy use of echo effects and tape speed manipulation.

Both albums are full of enigmatic and mysterious sounds, with coldness, aesthetic distancing, and quiet rhythms standing out. The track titles evoke from the enigma to the sordid, terrible and cynical; the narrative suggests something profound and mysterious, with spontaneous, chaotic and confusing elements, slightly strident, overall concluding in a powerful atmospheric ambient aesthetic.

With their reissuing effort, the Institute for Danish Sound Archaeology is bringing the opportunity to enjoy or discover works that may have remained hidden to a broader contemporary audience. In the case of Christensen, it’s an excellent opportunity to revise his important role in experimental music and sound art across several decades. Christiansen’s life and body of work reflect his overall goal for collaboration and challenging the norms, the boundaries between artistic disciplines and his own preconceptions; a vibrant example of praxis in constant flux.