Text by Agata Kik

The realm of contemporary art is vigorously growing and morphing. While all definitions of practices and institutional frameworks have shifted and blurred, contemporary art is an expanding field of broader knowledge and practices.

This results in increasing inter-disciplinarity and multiple ways of knowing, which has created a crisis of knowledge, rather than a crisis of expression for artists. Nonetheless, there have been shifts in artistic forms and practices. The most significant change in curating contemporary art practice has been the opening up of spaces for conversation and discourse, closely related to notions of performativity and interdisciplinarity.

Navigating between the ephemeral and the material, floating above the sea of signs and their categorical subordination, the practices of artists Vanessa Lorenzo and Debbie Ding collapse the boundaries between science and art, matter and mind, the active and the static. The challenge of conveying their thoughts, exposing their process of questioning and displaying formless work provides a rough ground from which their artworks emerge. Their two different mixed media art practices constitute methods of working with speculative design to expand ways of perceiving the world.

Originally from Singapore, Ding investigates archaeological and historical finds, designing new approaches to collecting, mapping, labelling, organising and interpreting assemblages of information. In a way, her art practice explores diverse ways to express the pursuit of knowledge. On the other hand, Lorenzo mixes biology and technology to expose the entangled essence of nature-culture subsistence. Her works are devoted to investigating the more-than-human ways of environmental existence.

CLOT Magazine and so-far brought Ding and Lorenzo together to discuss the new ways of constructing conventions of the contemporary moment and the limitations of representation. They chat about working with organic matter, the “internal workings” of a material form (animate or inanimate), technological design and public participation in interactive art and fusing scientific experiments with creative activity in an artist studio. Both point to the discursive nature of art displayed in the contemporary scene while creating affective spaces beyond the sphere of linguistics.

Debbie Ding: When I first started looking into your work, I wondered how you get people to understand your work. How do people react to your work? I ask this because understanding your art may require background information or knowledge. For my work, I also put a lot of research into a project, but when someone sees the final result, they only see a small part of it. Therefore, it can be challenging for the audience to appreciate the complexity of it.

Vanessa Lorenzo: This is an interesting question. I try to make sure that the places where I show my work provide parallel platforms that allow me to present the ideas behind a project through a talk or discussion. My inspiration for this more holistic approach comes from Dunne & Raby1 and the school they created: a way of presenting complex ideas in which you invite people to participate in understanding the context. I also like to develop this idea with workshops, which is a format that allows for a more extended time to talk about my work or specific parts of it.

Ding: I think talks or workshops are some of the best ways to speak directly to people. I also think there can be different ways of making this beyond the more traditional formats like some of the workshops you give. I’m thinking of Expanded SensoriuM2, Alienated Landscapes3 or Bioprinter | Bacteria As A Post-presentational MediuM4.

Lorenzo: Yes, I agree; it’s a compelling way to produce and disseminate knowledge, even though running a workshop takes a lot of effort. It’s a more direct communication platform, and you need to balance your creative idea and the practicality of executing something meaningful and of quality. What is your perspective on this? Considering that your work is pretty complicated, how do you collect, document and share your knowledge and ideas?

Ding: I would say this is something I’m still trying to figure out: doing these workshops and thinking of how to communicate my ideas and how these relate to the aesthetics of the work — something I also see in your work. I consider how to pass on knowledge and how to inform communities… To me, choosing the format of the work and the documentation process is also a way of communicating it. You’ve described your works as “interactive media assemblages5”, which I think is very similar to how I have described my work in the past. Could you explain more about your understanding of this concept?

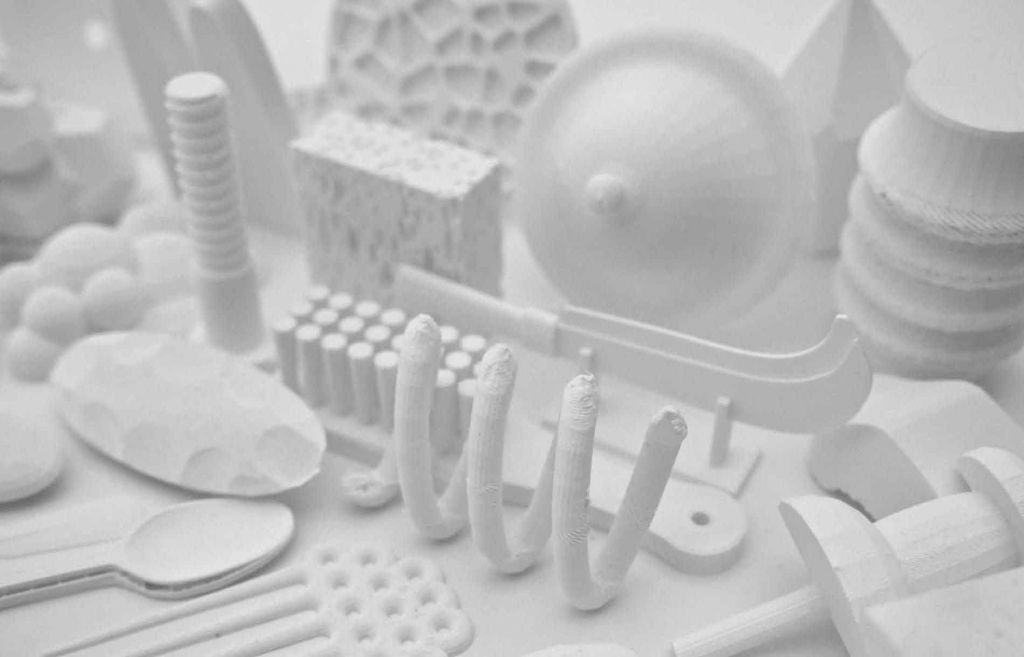

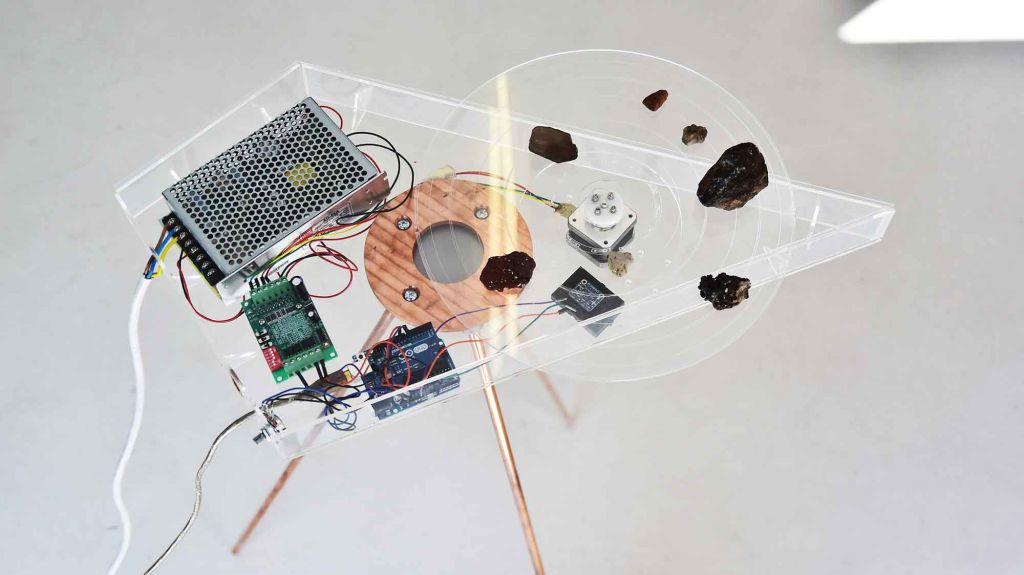

Lorenzo: Yes, I use different media in my work, and I call it “interactive media assemblages” because we have access to all these platforms and technologies like video, speculative machines and sounds. I see it as a way of stepping out from pure design and creating art through devices and objects using processes closer to the ones used in interaction design.

Currently, I’m working on a new project based on the figure of the Green Man6 with vegetal prosthetics and speculative body modification through technology. Though this representation is based on a pre-Christian figure sculpted in some churches across Europe, this hybrid figure of human and plant can be found represented in cultures worldwide. The project is in its initial stage; unfortunately, it was impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. For a workshop, I’ve come up with the idea of making a sort of “biocompatible biological skin”. I thought about what I could do to push forward my intersectionality with biotechnology while simultaneously pushing forth my practical interaction with the audience.

What about you, Debbie? Have you been teaching regularly?

Ding: In my day job, I teach Interaction Design at a polytechnic in Singapore, where the role is focused on imparting practical design and technical skills to the students. As someone who was largely self-taught, it has been interesting for me to understand the traditional approaches to education so that I can reinterpret them on my own terms. In Singapore, I intentionally separate my art from my design teaching. Design is often about function, but I choose to make art because it is not tied to money or a specific function, so I can also make things which go beyond those constraints. I also try to inject that into my teaching, so my students understand there is a way to explore beyond those constraints.

When I see other artists working in media arts, I’m always curious about their perspective on the aesthetic. What role do aesthetics play in your artworks? What was your own design background?

Lorenzo: I come from a very technical background. I studied engineering and industrial design; half of my life was dealing with metal, huge machines and modelling for these machines or cars. Then I started a media design MA in Switzerland and met the biohacker community there. When I started working with these biomarkers and their organic compounds, it felt almost like I was doing something prohibited, mixing electronics with the wet lab. I found it very challenging. On the other hand, when you come across speculative projects — such as your New BiologisT7 project in which you question new species and future extinct species — it’s really powerful to be able to make people think something is possible through the techniques we are using.

Ding: Yes, I would describe this power you mention as exploring the line that separates observations or research and people’s actual beliefs. It is a process of figuring out how to express something speculative and how to make it feel real enough so that people think it is a possible reality. I remember friends whose projects were picked up by the media as if they were real things, even though their projects were speculative designs and no longer had the life they were made for. The projects turned into something new because of the reinterpretation.

Lorenzo: I’m curious about the archaeological aspect of your work.

Ding: The Library of Pulau Saigon began from an archaeological catalogue I had found about Pulau SaigoN8, a former island in the Singapore River. The island no longer exists but appeared in maps and street directories until about 1975. A rescue dig had been conducted on this post-18th Century archaeological site, so I became intrigued about the story of the erasure of the site from public memory. I contacted the archaeologists and went to see the things myself, but I felt there wasn’t much to look at. The site was pretty topsy-turvy due to dredging, so the oldest items were at the top instead of the bottom. I felt like so much of Singapore was about erasing itself, so I wanted to investigate the meaningful things for me or ask questions that never really got answered. So my early works were about creating datasets, creating strange little archives and speculating on the physical form of Singapore and its environment.

Lorenzo: This reminds me of when you asked me how I store my project information.

Ding: Yes, I was thinking that everything is digital and virtual these days, but what about the biological and living material you use for some of your projects? How do you go about storage and documentation?

Lorenzo: When I started making art, I kept a small booklet with details of each project. I stopped doing this because it was very time-consuming. I learned from the biohacker and biomarker community that, as we discussed at the beginning of this conversation, documenting and disseminating knowledge is a very important part of the process. During my first project, I learned how to write protocols and replicate experiments from the people working in biology.

Ding: Do you still have the moss you used in MOSSPHONE project?

Lorenzo: Yes. In my studio, I have a little garden with some round plates where I keep my mosses growing. This small garden is a way of storing. I have a lot of that stuff in Petri dishes and plastic boxes too, like all the bio-printed materials and structures.

Ding: I keep a fair amount of soil and rocks from my projects; some of these rocks are quite muddy. I love rocks, but the ones I have are mainly human-made because those are the main kind of rocks I can get in Singapore.

Lorenzo: Rocks are fascinating because they are little pieces of territory that can develop into something else. When you say you collect mud and rocks, I picture much life happening there.

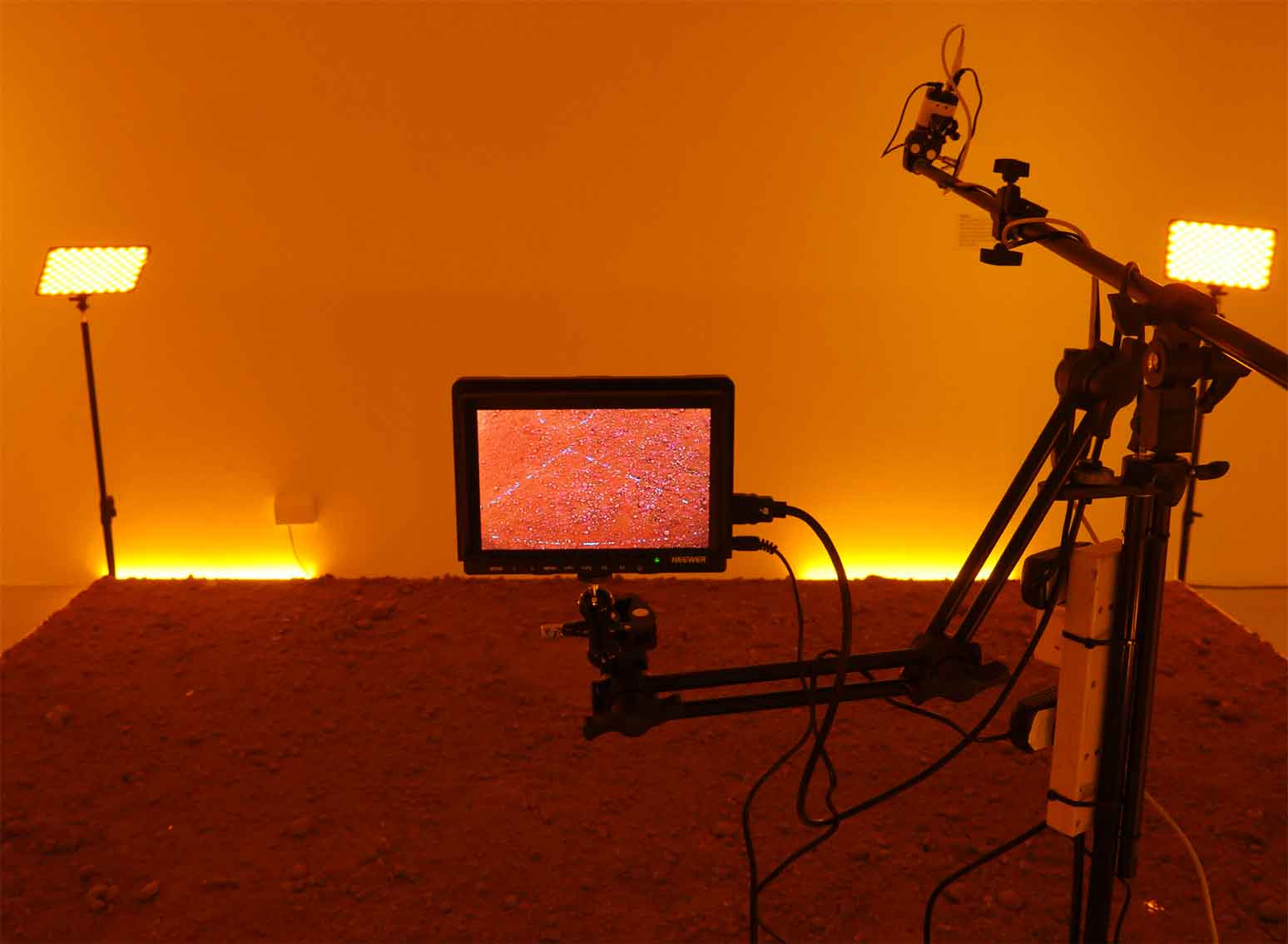

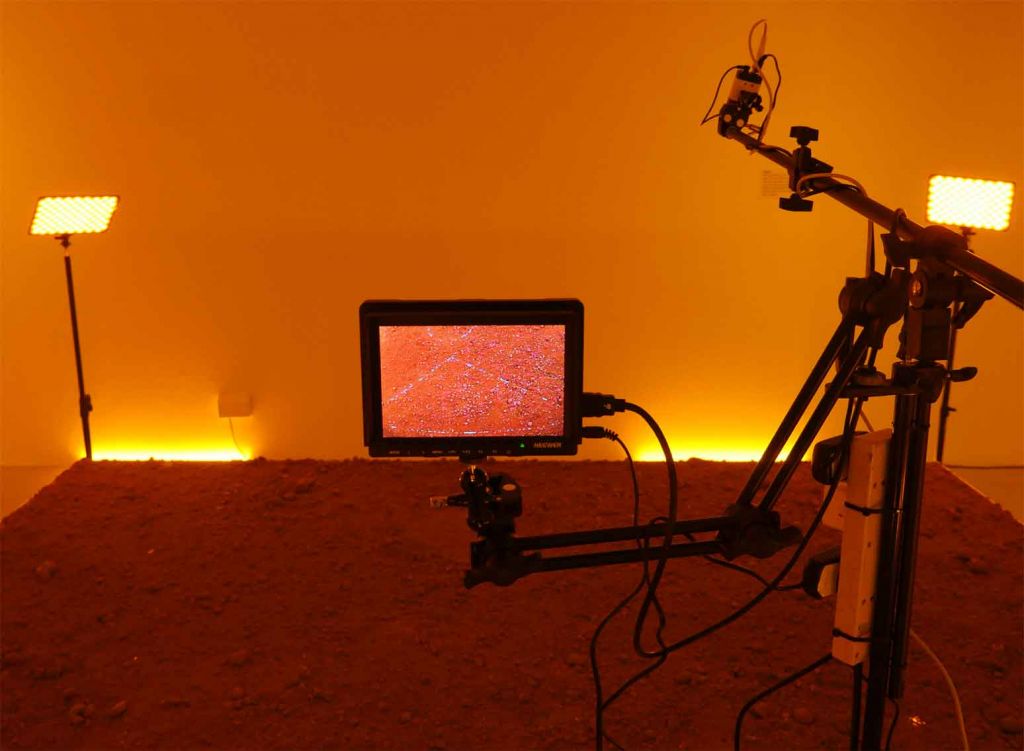

I worked quite a lot with asteroids. Initially, I collected certification data and sent out memories of asteroids. Then I came across a meteorite in South Africa. It has a characteristic red colour that resembles Mars rock. I collected these pieces, some of which I used for interactive sculptures and others I’m observing to see what develops when combined with the Earth’s climate. I’m not thinking about the minerals but rather about new collages from other planets that can enrich our biodiversity, especially since the Earth is facing such a significant loss on this front.

This makes me think of future-extinct species — which one would these be?

Ding: I thought it could be snails. I am very fond of snails; they’re like rocks with faces on them, and I had pet snails for quite some years until recently when my baby’s needs exceeded of my ability to take care of the snails. The snails from Singapore have been out-competed by Giant African land snails9. We have a lot of tiny tropical snails that are not as aggressive or hungry for life as the giant invasive ones. So if I have to think of fossils and extinct species, my mind turns to the delicate local snails for some reason.

Lorenzo: There is a political perspective here since we can talk about native and non-native in a way. But what is native anyway?

Ding: Actually, I never realised that the Giant African land snail was not native to Singapore until I went to the UK and I saw they were being sold as exotic pets. These snails are so common in Singapore and can be found all over the grass, so I had mistaken them for the “default” native snail. I kept some native UK garden snails (Cornu aspersum) when I lived in London, and when I was moving to Singapore, I wanted to bring some of my pet snails back, so I wrote to the authorities to ask if I could, but I wasn’t allowed.

The Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore responded by saying that the snail would have been classified as food. Additionally, the Cornu aspersum was considered a “great threat” to crops and ornamentals in Singapore. I wonder if I would have been allowed to bring the Giant African snail, the most common snail in urban Singapore but technically invasive. I thought, to what extent is something native or non-native?

Lorenzo: Yes. This is something we all are realising now. It’s also enlightening when you realise that the “normal” you’re used to is not that normal anymore.

Ding: Maybe other people have a completely different reality. Nowadays, we all live in our own bubbles of understanding. Taking us back to your question, what do you think a future-extinct species might be

Lorenzo: Inspired by one of my latest workshops, which involved imagining a species you would like to create hybrids with, I have been thinking quite a lot about humans, beans and other plants. For example, in terms of functionality, what could you take from a pre-existing species and give to humans in order to change or subvert how we operate?

I started to read a lot about plant horror and these horrible movies about gender. It crossed my mind that it would be a good idea to become a little bit more plant-like — to become phototrophic and begin consuming energy from the sun. This could have political, ecological and economic consequences that could flip the whole reality of how the system works.

Ding: During the pandemic, I have been thinking about how the world would look without people, but then I was thinking about how people are so strong that they always find a way to survive. We spend thousands of hours practising and learning things. My baby just turned one, and I thought about how much care and work has gone into each human. I’ve never really appreciated it until now. We see people that may not be mindful of what they do, but at the same time, I feel that people have the opportunity to learn, grow and change because that’s what people have been doing since the day they were born.

CLOT Magazine: If you could imagine a collaborative work together, how would you envisage it to be?

Lorenzo: We have some ideas about snails during this conversation, so let’s think about how to frame them.

Ding: Yes, indeed. We have a lot of similar interests, and you’ve gone a lot further into the practical level. I’ve never seen the bio wet labs in Singapore on the same scale I saw in Europe.

1 Dunne & Raby is a London-based design studio which uses design as a medium to stimulate discussion and debate amongst designers, industry and the public about the social, cultural and ethical implications of existing and emerging technologies.

2 Vanessa Lorenzo, “Extended Sensesorium”, Hybridoa, 2019. www.vlorenzolana.myportfolio.com/extended-sensesorium

3 Vanessa Lorenzo, “Alienated Landscapes”, Hybridoa”, 2017. www.vlorenzolana.myportfolio.com/alienated-landscapes

4 Vanessa Lorenzo, “Bioprinter | Bacteria As A Post-Presentational Medium”, Hybridoa, 2017. www.vlorenzolana.myportfolio.com/bioprinter

5 Vanessa Lorenzo creates hybrid media ecologies embedding people, the more-than-human and the technologies that intertwine them, which she terms as ‘interactive media assemblages’. Vanessa Lorenzo, “Short Biography”, Hybridoa. https://vlorenzolana.myportfolio.com/biografia

6 Prudence Gibson, “The Green Man: the desire for deeper connections with nature”, The Australasian Journal of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology, Vol. 6, 2016. www.openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/Swamphen/article/view/11398

7 Debbie Ding, “New Biologist”, DBBD Index of Works, 2014. www.dbbd.sg/works/newbiologist.php

8 Pulau Saigon was a small island in the Singapore River in between the banks of Robertson Quay. It was merged with the mainland when the western arm of the river was drained in 1972. Debbie Ding, “The Library of Pulau Saigon”, DBBD Index of Works, 2015. www.dbbd.sg/works/the-library-of-pulau-saigon.php

9 The African Snail (Achatina fulica) originated in Africa and its presence in Singapore was first recorded during the 1920s. It is thought that trade between East Africa, India and Malaya resulted in its dispersal to Southeast Asia. “Giant African Land Snail”, Appreciating Nature with Flo, 2017. www.flonatureblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/16/giant-african-land-snail/

(Images courtesy of the artists)

This is the second in a collaborative interview series between contemporary artists on the so-far platform and those within CLOT Magazine’s network. The format attempts to seek out alignments between new media practices across the globe and forge serendipitous networks through dialogue and open sharing sessions. This series is supported by the Embassy of Spain in London.