Interview by Lyndsey Walsh

The Stockholm-based collaborative duo Goldin+Senneby have found themselves returning to the question and investigating the models, systems, and metaphors that make up our understanding of the world. Working together since 2004, Goldin+Senneby, composed of artists Jakob Senneby and Simon Goldin, have explored the means in which economic structures come to shape society, often drawn to what they refer to as the structural correspondence between conceptual art and finance capital, drawn to its (il)logical conclusions.

However, in recent years, their work has shifted its focus to questions related to care, ecology, and the politics of diagnosis. Continuing their work with more personal stakes than ever before, Goldin+Senneby’s first-ever US solo museum exhibition, Flare Up at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, places the artists’ experiences of living with Multiple Sclerosis front and centre. The exhibition, originally organised by Accelerator at Stockholm University, has been adapted for the List Center and will run from October 24, 2025, to March 15, 2026.

Flare Up explores the metaphors of flare-ups of an autoimmune disease, crossing the boundaries of human and non-human agents. Connecting with genetically engineered pine trees, which have been modified to overproduce the tree’s own immune products of resin as a renewable alternative to fossil fuels, the exhibition engages with commonly recurring metaphors of autoimmune conditions, such as a body at war with itself and an overactive immune system. Included artworks Resin Pond materially flood the exhibition space, redirecting the flow of movement for visitors, while Crying Pine erects the pine tree entrapped in a block of resin, overcome by its own overactive immune system.

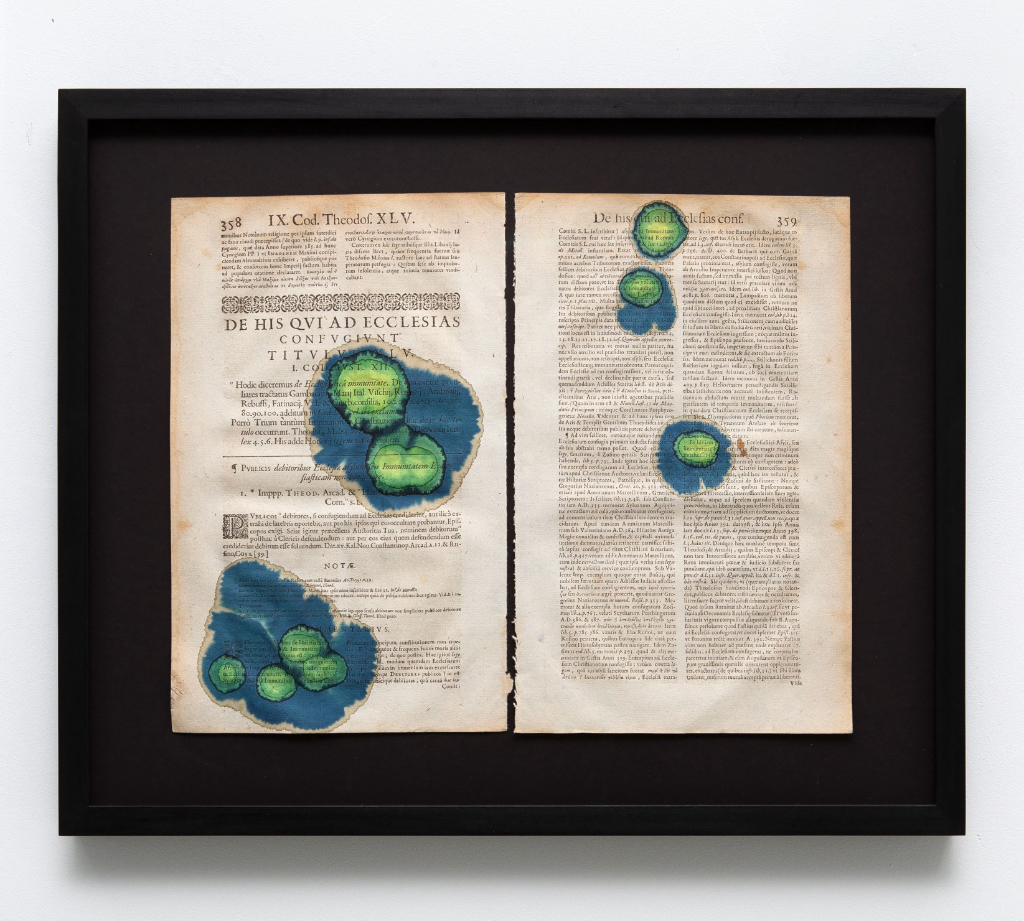

In addition to the works of Goldin+Senneby, their collaborative novel-in-progress by American writer Karie Kitamura is also featured, providing a two-part narrative exploration of a singular world. The story ties together a pine tree, a supercharged immune system, and a stranger whose identity and biology become questions as they pursue treatment for their illness. This collaboration with Kitamura expands on the ongoing creative relationship with Goldin+Senneby, which began in 2018. These textual excerpts from their collaboration with Kitamura align with Goldin+Senneby’s essay Regions of Interest, which delves deeper into the prioritising and valuing of the “white spots” found in MRI scans in MS pharmaceutical research.

Goldin+Senneby’s After Landscape series and Schluckbildchen (Swallowimage) are exhibited alongside these works. Their After Landscapes series offers an emerging historical examination of contemporary climate activist actions targeting high-profile artworks. At the same time, Schluckbildchen (Swallowimage) unveils the multispecies material entanglements among art history, medicine, and pharmaceuticals in the pursuit of healing treatments. Lastly, Goldin+Senneby’s long-term exploration of capitalist dynamics and the role of labour, featured in their artwork Lego Pedometer Cheating Machine, has been included. Now recontextualised in the context of illness and disability, these DIY devices are designed to cheat a smartphone’s pedometer for the sake of health insurance companies’ “activity goals and requirements” of “shared” health data and present a haunting reality of the continuing hyper-surveillance of bodies to adhere to ableist standards.

While their practice no longer comes from a perspective of the withdrawn or disembodied, Goldin+Senneby continue their inquiry, asking what it means to inhabit a world where bodies, environments, and economies are increasingly entangled in states of escalating inflammation.

You have been working collaboratively since 2004, and during that time, you have described your work as exploring the structural correspondence between conceptual art and finance capital, drawn to its (il)logical conclusions. However, in recent years, you have shifted the focus or directed the intent of your creative practice toward what you have explained as questions of care, ecology and the politics of diagnosis. Please share with our readers a bit about your journey in collaboration and projects, and how you came to this shift in creative practice.

Jakob Senneby: Our work comes out of a continuous dialogue that goes in many different directions, but we’ve always tried to dig where we stand, so to speak. Our relationship has always been central to our work. And recently, we decided to focus more explicitly on the conditions of vulnerability and care that are at the center of our collaboration, and on the relationships with the many other collaborators we depend on to realise our work.

Simon Goldin: Until seven or eight years ago, much of our work involved attempts to “become virtual” or disembodied—to be present through absence. Our very first project together was an island called The Port in Second Life, the early online role-playing platform that prefigured the birth of social media proper. After two years, we burned out from doing “community art” in a virtual space that was active across all time zones.

Jakob Senneby: Way too many 3 am meetings! We decided to withdraw from all social media and, for about a decade, from all public appearances.

Simon Goldin: We began exploring questions of withdrawal through an investigation into financial and legal fictions. With Headless, we staged our own “act of withdrawal”, a body of work which only ever consisted of other people’s interpretation of the work, and which concluded with a ghostwritten mystery novel of the same name (published in 2015). Even as we were exploring the mechanisms of finance that allow for the abstraction or disappearance of people and corporate entities, we were also reckoning with Jakob’s illness and his hiding from it. Looking back, I think that has always been a hidden layer to our work.

Jakob Senneby: Absolutely, I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis twenty-five years ago, but I didn’t “come out” as having the disease until my legs gave me no other alternative. At the same time, Simon was more engaged in the details of the financial and legal constructs of offshore finance, for me, the question of withdrawal was always deeply personal: a question of dealing with my own fears and how to exist in the world without being seen as my illness. The projects that hinged on withdrawal enabled us to work at a pace that our collective body couldn’t—to circulate without appearing (or travelling), whether by employing avatars, actors or spokespersons to stand in for us. But at a certain point, it was just impossible to continue hiding. As my illness caught up with me, I became less able, but also less interested in inhabiting the ableist fiction of high-performance bodies.

Simon Goldin: So, what Jakob is saying is that although it is a profound shift in our practice, it is also very much a continuation of our methods. But with more personal stakes.

You began collaborating with Katie Kitamura in 2018, weaving your creative practice with her narrative craft. How did this collaboration come into being and how has it impacted your own process of making and knowing in your work?

Simon Goldin: We first got in touch with Katie Kitamura around the time of the book launch for Headless, a ghostwritten detective novel about our investigation of an offshore company in the Bahamas that was published in 2015. Triple Canopy organised a launch event in New York and invited various people to read excerpts from Headless and then comment on them. Katie was one of the invited readers, but instead of actually reading a chapter from the book, she had written her own, entirely fictional chapter, which she pretended was an excerpt from Headless. That really impressed us, and that’s how we first connected.

Jakob Senneby: A few years later, we suggested that we would gift her a small tree as the starting point for a collaboration. It was a genetically modified pine sapling, engineered to overproduce resin. And she said Yes! Although I’m not sure if she fully understood the commitment at that point.

Simon Goldin: The gift came with a strict protocol. To release the pine sapling from its lab in Florida, we secured special approval from the USDA to convert a room in Katie’s home into a “containment area”. Her entire family had to undergo safety training. If any part of the tree were to leave this one windowless room, she could face fines of up to one million dollars and seven years in prison.

Jakob Senneby: Yes, it was a very particular kind of gift, more like a gift and a curse.

Simon Goldin: That became the starting point of the novel. She began writing from the experience of becoming the caretaker of this pine tree with an overactive immune system. So, as a method, it involved placing Katie in a situation from which she could write.

Jakob Senneby: But then in the narrative she places my character—a “somewhat gaunt” looking man with a wooden cane named J.—in all kinds of situations… ultimately disappearing into an overgrowth of immunosuppressive fungi, in a particularly haunting scene.

Simon Goldin: So, the whole method is a call-and-response where we continuously impose situations and narratives on each other.

In Flare-Up, biological illness, ecological crisis, and technological intervention are intertwined, never self-contained. If we read the exhibition as diagnosing systemic conditions (autoimmunity, extractivism, overprotection), what kind of prognosis do you see emerging? Are these systems capable of recalibration, or are they locked into cycles of escalation?

Simon Goldin: Not sure we have any future prognosis to offer. We are more occupied with the frames that condition what we see. Because in the current frameworks of ”diagnosing systemic conditions”, the future is already here, right? It has already been modelled and predicted. And we don’t particularly like what we are seeing. So you have to shift the frame to get a different view. That’s what After Landscape is about, and also our works on the metaphors of autoimmunity.

Jakob Senneby: Yes. We all know how it ends. I’m more interested in how we care for each other along the way.

In your Triple Canopy essay Region of Interest, you call out the image of disease and how, in medicine related to Multiple Sclerosis, it is used in the place of disease, when the reality of living with a disease and the impact of the disease on a body are entirely disjointed from the prevailing visualisations of brain MRIs. This is true for many lifelong diseases and disease identities, where patients are transformed by the medical process into suppliers of diagnostic imaging, performing endless, often lifelong commitments of clinical labour, and becoming “specimens” along the way, which may or may not benefit them in their healthcare journey. What do you wish current medical paradigms would change, or re-evaluate, to move away from the “the image is the disease” model?

Jakob Senneby: Obviously, it would be nice with a medical paradigm that puts more value on my well-being than a system rigged to validate drug sales. But we are not pretending to have a solution or a new paradigm that will solve the mysteries of MS. What we are exploring is this space between diagnosis and lived experience. I often feel like I’m occupying two incompatible realms: that of medicine, where my body is measured and manipulated with incredible precision, and that of my own experience, where numbers refuse to add up, and limbs fail to process commands.

Simon Goldin: It’s a bit like the famous Max Ernst quote on surrealism as a stitching together of two realities that by all appearances have nothing to do with each other.

Jakob Senneby: Yes, that is very much how I experience my condition. Trying to stitch together reality is becoming increasingly surreal.

While you are working with pine in Flare-Up, you have also engaged in work with other species of tree, including the spruce in your work, Spruce Time. In this work, you draw us in with the catchy headline “The World’s Oldest Spruce has been Hospitalised in Sweden”. Why hospitalise a tree?

Jakob Senneby: You know the first European medical school was under a tree. Or so the legend goes, Hippocrates would gather his students beneath this single plane tree on the island of Kos, Greece.

Simon Goldin: And throughout history, hospitals and sanatoriums have always included trees as part of producing a healing environment. At the hospital in Malmö, where Spruce Time is installed, an ambitious arboretum was developed on the hospital grounds at the beginning of the last century. But over the decades, most of the trees have been cut down to make way for new hospital buildings. And the commission for this work was part of the latest massive hospital expansion, during which hundreds of old trees had to make way.

Jakob Senneby: The brief for the commission was to produce a ”monumental” artwork. Something that could be a landmark for the hospital. But we thought it would be more interesting to think of the monumental in terms of time. Deep time. And we had this story about the spruce that had cloned itself throughout the Holocene, which opened up this deep time of the tree.

Simon Goldin: So the work becomes a challenge to the hospital. As word spreads about the hospital caring for the world’s oldest spruce, the health and survival of the cloned tree become central not only to the artwork but also to the story and identity of this hospital.

Jakob Senneby: Yes, it’s a very public patient!

You have also given it its own incubator—a climate-controlled chamber integrated into the hospital’s infrastructure. What parallels do you see between medical care for human bodies and the technological care now required for nonhuman life in the Anthropocene?

Jakob Senneby: I guess from the tree’s perspective, it has successfully cloned itself throughout all of the Holocene. And now continues to secure its survival into the Anthropocene by cloning into this hospital incubator.

Simon Goldin: We thought a lot about how the incubator mirrors the hospital, and about this idea of ”patient-centred care,” which individualises each patient and atomises each diagnosis. There is something violent about caring for a single tree, without the context of the forest.

Jakob Senneby: But it’s also key to the work that the climate-controlled chamber integrates with the hospital infrastructure. That the cooling of the incubator comes directly from the hospital’s excess capacity, for us, this work is ultimately about dependencies: about making the world’s oldest spruce dependent on the hospital’s ecology, and making the hospital part of the tree’s ecology.

Your work, After Landscape, reveals and reconnects with the layer of climate activism applied to the protective “climate frame” of famous landscape motifs. By recontextualising climate activism and landscape paintings as part of an interconnected dialogue, you direct viewers to renegotiate how we look at landscape. What do you think is being renegotiated and by whom?

Jakob Senneby: We think of our intervention as an act of care. Working closely with a museum conservator to care for what is arguably the most important landscape painting of our time.

Simon Goldin: Yes, we see the climate attacks as a contemporary form of landscape painting. As you may know, the very concept of landscape was invented through painting. When the word ”landscape” first entered the English language around 1600, it was imported from the Dutch ”landschap” and referred exclusively to painted scenes. It took several decades before the meaning was extended to the natural world itself. We argue that this art-historical invention is central to how we frame nature as something external to ourselves to this day. And this must be one of the key questions of our time: How do we culturally re-inscribe ourselves as part of nature? That’s the problem the climate activists are up against.

Jakob Senneby: Of course, artists have dealt with this issue throughout the centuries. We sometimes think of ourselves as ”plein air artists”, with reference to the landscape painters of the 19th century who left the studio, and the idealised notion of landscape, to actually go out into the fields and get their hands and feet dirty.

Simon Goldin: Importantly, and unlike the iconoclasms of previous centuries, the recent attacks on landscape motifs have not damaged the historic paintings themselves but have stuck on the protective glass in front of them, also known as the ‘climate frame’. As paintings, they insist that we shift the frame through which we see the landscape!

Do you see the museum as a collaborator, a subject, or a contested space in relation to this project?

Simon Goldin: All of the above. The museum is the site of production!

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Jakob Senneby: I was about to say fatigue, or brain fog… or maybe capitalism. But then I realised that these are all the central motifs of our work.

Simon Goldin: Guess the question of creativity has never been the main issue for us. At least not if you mean ”coming up with ideas”. We have been more concerned with the method, the process, and how to practice together over time.

You couldn’t live without…

Each other.