Text by Iris Colomb

Ningrui Liu (aka Akira) is a multidisciplinary London-based artist from Shanghai who uses the I Ching as a compositional framework to approach performance, sound and visuals. She has experimented with multiple choice-making approaches involving this ancient system, ranging from embodied processes fueled by its spiritual roots to digital automation powered by bespoke Python scripts.

The I Ching, which literally translates as Book of Changes, is an ancient Chinese divination system structured through sixty-four unique hexagrams, each composed of a set of six broken (Yin) and continuous (Yang) lines. Each hexagram comes with a text that can be interpreted to answer questions. Hexagrams are typically drawn by throwing three identical coins and using the results to navigate their chart. The I Ching is anchored in the belief that everything is constantly changing; its purpose is to help us understand and adapt to various cycles and states of change and to remind us that nothing is unchangeable. The two types of lines symbolise a fundamental duality of opposed, complementary and interdependent forces. Artists, such as composer John Cage, have used the I Ching’s hexagrams to conduct systematic chance operations, determining the compositional elements of a piece in works like Music of Changes (1951).

Surprisingly, Akira’s encounter with the collision of the I Ching and artmaking occurred solely through Western references. This pivotal discovery coincided with a time in which, working as a film editor in Beijing, the pressures of her job had Akira caught in a vicious cycle many of us will unfortunately recognise. We have all at least heard of this toxic cocktail in which an uninterrupted state of urgency is fused with a merciless set of impossible standards, with no hint of validation and no space for mistakes. For Akira, this led to a rising frustration, a deep sense of disconnection from her own body, and the impossibility of thinking beyond the tasks at hand.

It was in response to the constant pressure to simultaneously perfect her skills and improve her efficiency that Akira opened the 2002 volume The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film. On page 313, the wisdom she sought met unexpectedly ancient echoes, as the award-winning American sound mixer and film editor introduced the idea of editing a film using the I Ching. This idea, which he presented as an interesting exercise, pointed to an exciting way of alleviating the burden of constant choice-making Akira was faced with and went on to nurture her desire to reconnect with her own art practice and to return to the UK, where she had previously studied.

In describing the I Ching’s significance in her culture, Akira states that it is behind, underneath, everywhere; she goes on to explain that despite this, it is seldom engaged with directly. While The Book of Changes is unlikely to appear in most households, except academics’, it can sometimes come up around weddings or other situations involving significant life events, for which a fortune teller using the I Ching might be called upon. However, according to Akira, divinatory practices associated with the I Ching tend to be approached with caution or discouraged in contemporary Chinese society.

Young people in China are much more interested in Tarot and tend to see the I Ching as just an old book, she explains. Despite this, a kind of reverence seems to remain and is notably felt in Akira’s mother’s reaction to her daughter’s project Film of Changes, (or How I Free Myself with Rules), in which she can be heard and seen making fun of Akira for using the ancient divination technique for something as trivial as art-making. Overall, British people are much more interested in the I Ching than Chinese people. Akira tells me she learnt to use it shortly after moving back to London, and it was also then that she was introduced to the practice of John Cage.

When Akira first started working on her Film of Changes, she was guided by her interest in the I Ching’s spiritual side and delved into the enigmatic images she found within each hexagram’s explanatory text. In the film, she can be seen interpreting them like performance scores and running, balancing, jumping and stumbling in front of the camera. Akira’s multilayered film, through which multiple genres, including video art, documentary and making-of, collide, constantly blurs the boundaries between art and life, process and outcome, chance and choice. As the filming process progresses, viewers witness this embodied approach change Akira’s relationship with her environment as the I Ching pushes her to experience it in new ways.

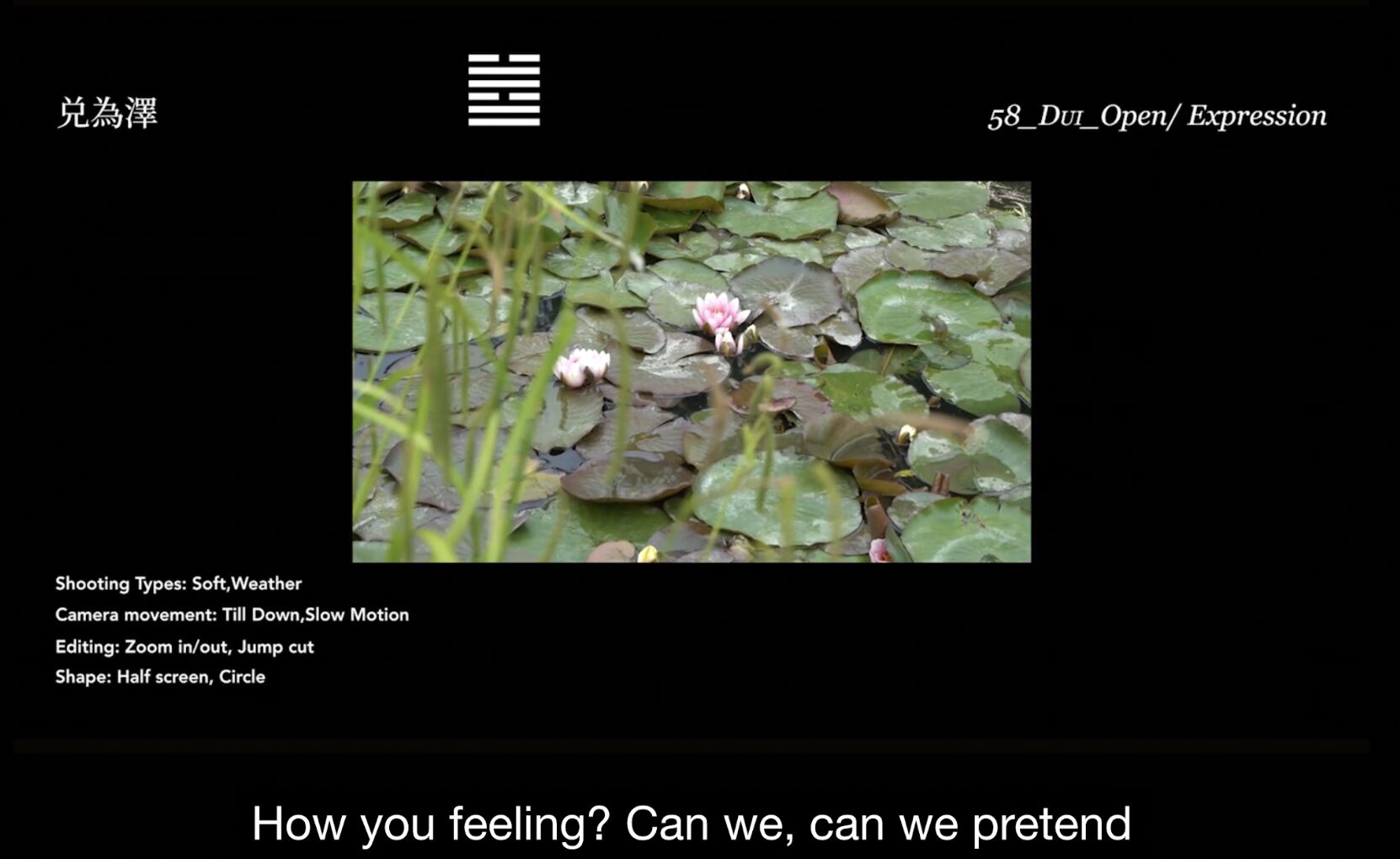

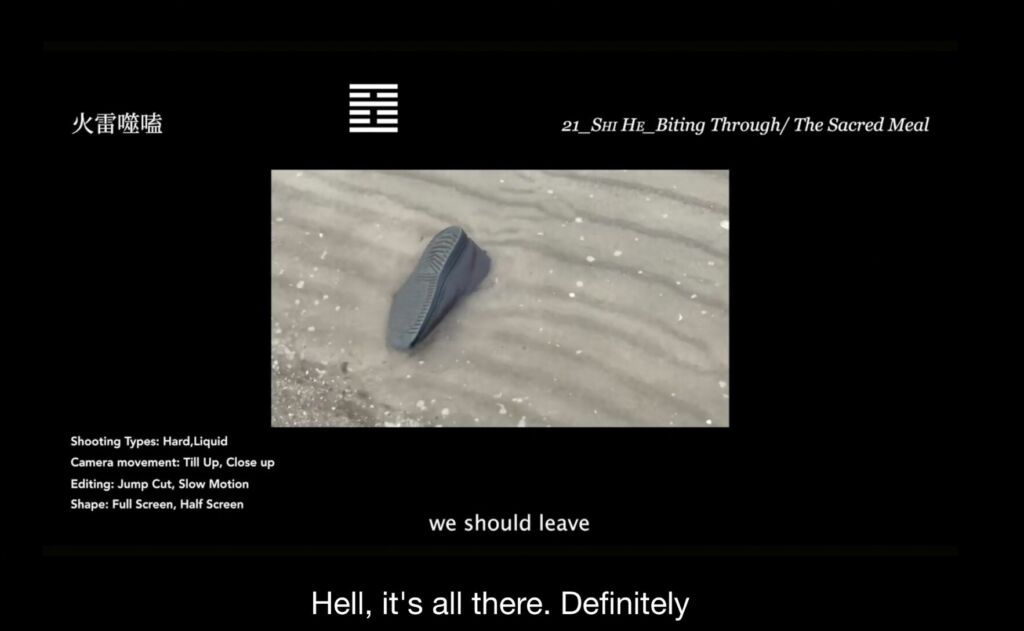

As the film progresses, Akira adopts a more systematic approach, in line with that of John Cage. She starts developing her own charts and delegating further creative choices to the I Ching. Beyond the film’s subject matter she also chose to entrust it with camera movements, shot lengths, editing style and sound. Eventually, as her method’s structure expanded and complexified, she turned to Python scripts, allowing her to produce an entire set of instructions for each film in a single click.

However, the specificity of the system made its instructions increasingly difficult to follow and evermore incompatible with Akira’s physical surroundings. Faced with excessive layers of constraints and a growing pressure to perform impossible tasks, Akira came to feel caught once again in a situation akin to that which she had endeavoured to escape through the use of the I Ching. Although she concluded that her Film of Changes’ choice-making method had not achieved its intended result, there can be little doubt that new and fascinating possibilities emerged from it.

It was through her film and with a view to developing its sonic side that Akira’s experiments with the I Ching branched out into other art forms, including music and collaborative performance. At first, she attended London’s Lofi workshop, a space for collective experimentation and asked a few musicians to interpret hexagrams sonically. Then, her own engagement with improvisation led her to join Noisy Women, a feminist improvising collective founded by musician and composer Faradena Afifi. Soon she developed two collaborative projects of her own: duo Tigersonic Vs Akira and trio Etudes Study Group.

While Tigersonic Vs Akira’s first album Chance Noise #1, described as equal parts composition, chaos, and cosmic joke, involved a return to a more spiritual and intuitive approach to the I Ching, through the Etudes Study Group, Akira enjoys a new embodied form of chance. In this trio, multidisciplinary artists Jo Morrison and Felix X Tigersonic join Akira in performing with sound artist Sharon Gal’s ‘Etudes’. This deck of 78 cards is a set of scores and propositions, developed by Gal as a tool to inspire and trigger the imagination. Each Etudes Study Group performance begins with the same gesture and its inevitably different result. Akira throws the cards into the air and lets them fall to the ground before exclaiming, Unfortunately, it won’t be cleaned up by itself. She then proceeds to read them aloud one by one, gradually straightening out the performance’s unique mess.

In discussing her relationship with improvisation, Akira tells me that she enjoys the presence and commitment it requires and its resistance to classification and evaluation, There is no failure in improvisation, she explains. However, the subtitle of Akira’s Film of Changes (or How I Free Myself with Rules) echoes again through this new framework as even in her improvisations, there is a structure, there is a focus. This is achieved by doing one thing and one thing only and improvising around that constraint in each set, If I am reading the cards, I will just read the cards, she says.

So, instead of using the I Ching to make choices, why not use ChatGPT? LLMs and The Book of Changes share the same underlying purpose: making predictions. While the I Ching is, and has always been, a divination method, at its core, Machine Learning utilises pattern recognition to forecast future outcomes. Another structural link between the I Ching and computational tools lies in the structure of hexagrams whose set of broken (Yin) and solid (Yang) lines reportedly inspired the framework for binary code. In our discussion, Akira also highlights that both the I Ching and AI can offer ways to let go of control. So, could Large Language Models like Chat GPT be an equivalent tool for systematic choice-making?

One way of answering this question simply involves pointing to the corporate context and extractivist biases and practices that condition smooth LLMs such as ChatGPT, pushing us back into the all-too-familiar race for perpetual progress imposed by toxic workplaces such as Akira’s back in Beijing. This would lead us to then consider the I Ching, this ancient system, pervasively embedded within Chinese culture, distrusted by contemporary Chinese society and overlooked by its younger population, as an awkward force, the complexity of which allows it to resist the tyrannical pull of perpetual growth and productivity.

However, as Akira explains, while AI scrambles to give us the best possible solution, or worse, to present us with a dizzying multiplicity of options, the I Ching simply offers us one answer; in Akira’s words, it tells us where we are right now. Beyond its systematic side, the I Ching’s focus on cyclical processes, through which no step can be skipped, makes it a tool that demands presence. While ChatGPT, which is increasingly being used as a way to cut corners, represents a shortcut, allowing us to skip straight to its version of the best possible outcome, the I Ching allows us to live through a choice-making process, to both witness and experience a choice’s emergence.

Beyond this, Akira’s description of LLM-led choice-making as a situation in which nothing happened, no one lived anything, no one had any experience leaves me wondering whether the illusory collaboration we experience with ChatGPT and its eerily eager and consistent alignment with our views might facilitate a new kind of solipsism, a new layer of disconnection, of abstraction and absence from the world. In contrast to this Akira sees art’s purpose as bringing people together, she believes in its healing properties and its propensity to bring about shared joy. Her attempts to create a new artmaking method has certainly brought her closer to these experiences by allowing her to explore new ways of being present, both individually and collectively and by embracing the unexpected byproducts of ever-changing processes.

In order to figure out how to write this article Akira walked me through the I Ching divination process. Since this was unplanned, we had no coins and were forced to improvise. After looking around us, we settled on using some paper cups we found and crushed into shape. Following Akira’s instructions, one by one, I pulled 13, 30 and 44. Other than the idea of writing the article properly, which all three hexagrams seemed to be insisting on, they also pointed to shared understanding, enlightening sparks and unexpected encounters.