Text by Caterina Avataneo

In recent years, a significant portion of contemporary art has turned to murky and confrontational atmospheres, whether through hybrid forms, ghostly presences, or oneiric visions. The resurgence of this obscure sensibility arguably coincides with a shift in how we culturally understand, among others, the ecological crisis: the urgency to reconsider nature as a complex, interdependent system, intertwined with the structural violence of extractive economies, colonial histories, and environmental degradation.

Ecological discourse has moved from a purely scientific register to a psychosocial one. It is within this epistemic and emotional transition that the Gothic can become newly relevant as a theoretical framework, offering a symbolic language capable of giving form to the darker and ambivalent dimensions of ecological interdependence. Artistic practices can function as means for opening spaces in which the crisis is not merely brought to light, but felt and embodied. Through evocative materialities or narratives that exceed human exceptionalism, these foster new forms of liveliness that slip away from the classic Western dualisms around the notion of darkness.

The Gothic, after all, has long framed nature as an active, significant force, capable of unsettling and influencing the human. Where Romanticism idealised wilderness, Gothic narratives foregrounded its weirdness, transforming nature into far more than passive scenery: a site in which rationality frays, the subconscious surfaces, and moral or psychological dissolution reigns free. In doing so, they manifested modern anxieties about the natural world—its excess, its resistance to mastery—while exposing the ideological violence embedded in centuries of patriarchal domination.

This entanglement becomes even sharper in the present era of irreversible anthropogenic destruction. Much contemporary art has increasingly focused on making its structures of violence visible, denouncing how the relationship between humans and the natural world mirrors the violences enacted upon marginalised bodies—a connection long articulated by ecofeminist and decolonial thought. Once these structures become collectively legible, what remains to be expressed is how they are metabolised, exploring our deepest anxieties concerning this very notion of interdependence.

In classic Gothic fashion, fear coexists with curiosity: an impulse toward experimentation and a desire to probe shifting notions of “nature” and how we situate ourselves within it. When the Gothic Nature—porous, sentient, libidinous—meets ecological thought, it opens a conceptual space for imagining forms of environmental and interspecies identity.

The ecoGothic emerged in the 2010s as a mode that sidesteps both pastoral idylls and the apocalyptic fatalism typical of ecoHorror, simultaneously exploring the implications of such inextricable relationships and the anxiety of inhabiting a damaged world. Scholars such as Sharae Deckard, in her contribution to Twenty-First Century Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion (2022), expand this genealogy by proposing an “environmental unconscious”: buried strata of ecological trauma that return as spectral motifs in today’s culture, where long-suppressed environmental histories—oil frontiers, plantation ecologies, nuclear residues, invasive species—haunt the present.

Bregenz, Austria (2025). © Precious Okoyomon Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone, and Kunsthaus Bregenz Photo credit: Markus Tretter

In the lush, unruly installations by Precious Okoyomon, for instance, nature is inseparable from the historical marks of colonisation and enslavement—specifically referring to Black life in America, with its history of forced migration, exploitation and criminalisation. The artist stages rampant ecosystems in which invasive plants such as the kudzu operate as agents of memory, as well as embodiments of the entanglement between the natural world, racialisation and diaspora, while also carrying an irreverent regenerative potential for uncontrolled abundance.

Kudzu is a plant of Asian origin, introduced in the U.S. in the 1870s to stabilise soils exhausted by cotton monoculture, before it was banned for its uncontrollable proliferation. The choice of having this invasive species proliferate in installations such as To See the Earth before the End of the World (2022), at the 59th Biennale di Venezia relates both to its association with the ghostly displaced and disappeared bodies of the plantation system, and its interference with capitalist notions of productivity as well as seemingly benign, but deeply anthropocentric, notions of environmental sustainability.

Okoyomon’s poisonous gardens devour as much as they nurture, their “evil roots” undermining any notion of nature as passive or innocent. the sun eats her children (2023), at Sant’Andrea de Scaphis, Rome had an animatronic teddy bear resting within an Eden-like garden pullulating of poisonous butterflies. It had its wide and cute eyes fluttering in and out of sleep, before releasing a terrifying scream that unsettlingly reminded how ecologies of pleasure are inextricable from histories of pain. Teddies recur throughout Okoyomon’s practice, appearing in erotic drawings or as monumental, fluffy sculptures.

Like treasured childhood toys, they function as relational tools, signalling an inner dimension that is central to the artist’s practice and occupying a space that is simultaneously soft-core and infantile. If the orgiastic dimension of Okoyomon’s practice introduces forms of brat deviation, through which violence is undone mischievously, it also unveils the dissolution of the self in the encounter with the other: an openness toward the destructive drive of nature, and the possibility of being consumed by it (no wonder Precious is a skilled chef too!). The artist has often talked about their fascination with Bracha Ettinger’s notion of “fragilization”, an ethical mode of relation in which subjectivity becomes porous, and transformation becomes possible through shared vulnerability.

Okoyomon embraces this permeability as a way of encountering the nonhuman world without defence, allowing the self to be undone, reconfigured, or even devoured. Their recent exhibition ONE EITHER LOVES ONESELF OR KNOWS ONESELF (2025) at Kunsthaus Bregenz included a creepy installation of cute teddies assembled from dismembered plush fragments, collected by the artist over the years. These beings appeared gently hovering in the space while disturbingly hanging by their necks. Angel-demons, embodiments of a subjectivity that loses itself by merging with the other.

In a similar vein, Miriam Austin’s layered practice generates milieus in which interrelations between kingdoms—the botanical, the mineral, the animal, the human and the technological—take place in ambiguous encounters interrogating notions of kinship. The artist fuses organic and synthetic materials into posthuman anatomies that are both mournful and rich with life; and she draws from methodologies of decolonial and feminist perspectives, as well as myths, fiction, and personal heritage, to create imaginary dialogues among nonhuman agents.

For instance, her show Isthmus at Cripta747, Turin (2023) grounded in an imagined dialogue between the River Po and the River Great Ouse, where riverine myths and extractive infrastructures from the Po Valley and East Anglia converged into a series of sculptures that seemed simultaneously lifeless and resurrected, beautiful and abject. The show built upon a classically Gothic trope, as it imagined the two rivers whispering their secrets through the pipes of quarries and mines that populate their spectral fenlands, letting drowned mysteries resurface into sculptural bodies that formed a delicate installation.

Their materiality was deeply bound to the territories Austin explored, and their form was inspired by centuries of agricultural modification and industrial extraction, functioning as archives of past climates and geological trauma, as well as sentinels of a haunting future in which water is at once scarce and over-abundant. Their spectral character aligns with what Deckard terms the “extractive Gothic”—a mode in which environments scarred by industrial histories imprint themselves on bodies, producing hybrid forms that are both testimonies and warnings. Crucially, Austin’s work is not a critique of extractivism, but an exploration of kinship under conditions of collapse: fragile, toxic, intimate, scary and boundary transgressive.

Ecological theory itself has increasingly insisted on incorporating a darker dimension in its discourse, encompassing a vocabulary for grief and dread. Timothy Morton’s Dark Ecology (2016) defines ecological thinking as “dark–depressing” insofar as recognising the Anthropocene means acknowledging the destructive agency of the human species—an epistemic and emotional shock that echoes the Gothic moment of revelation.

Like the investigator who realises the criminal is none other than himself. Yet, Morton claims, ecological awareness is also “dark–uncanny” as it unsettles Western modernity’s fantasy that nature is an exterior domain. Damaging the nonhuman world thus ultimately means damaging ourselves. Interdependence, in this frame, is terrifying yet necessary to acknowledge.

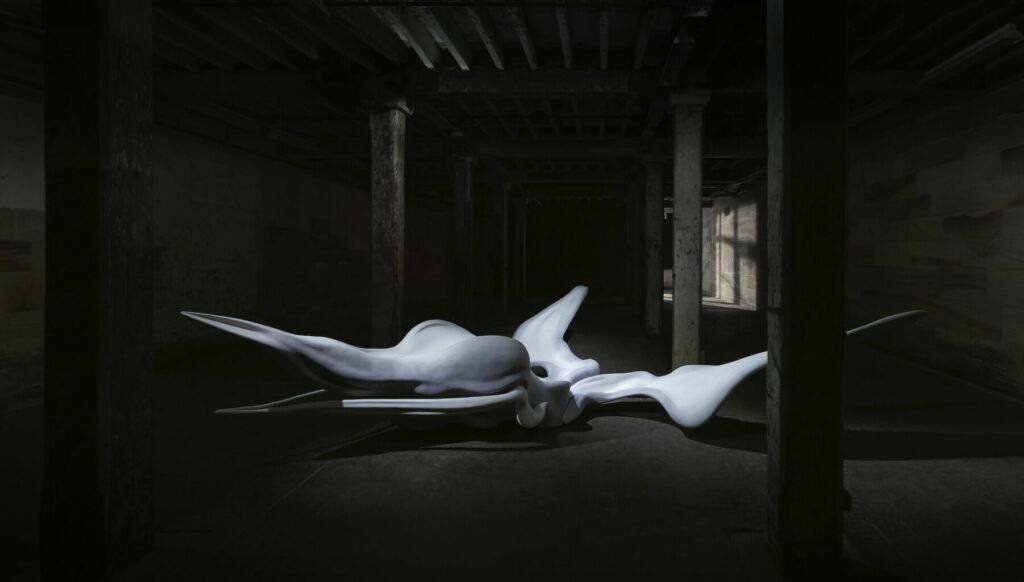

The Dancers III & IV, Two marine mammals invoking higher spirits, Marguerite Humeau (2019). Detail shot. Exhibition view at Centre Pompidou, Paris. Photo Credit: Julia Andréone. Courtesy the artist, C L E A R I N G New York/Brussels

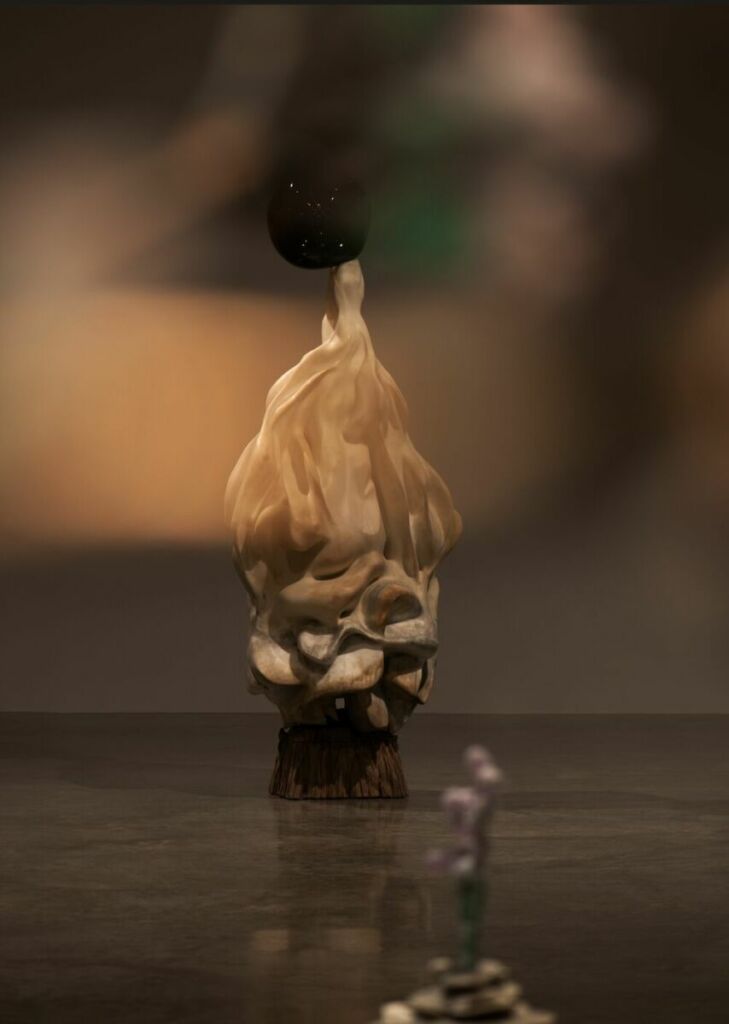

The Guardian of Ancient Yeast, Marguerite Humeau (2023). Exhibition view at ‘meys’ White Cube Bermondsey, 2023. Photo credit: White Cube (Julia Andréone). Courtesy the artist and White Cube

Many of Marguerite Humeau’s renowned installations stage the Anthropocene as a brief interruption in geological time, imagining futures in which humans are gone or subsumed by other species. Her sculptural series Mist/High Tide, presented worldwide in several iterations, wonders whether climate change might generate spiritual awakenings in animals becoming aware of their impending death. Drawing on studies of animal mourning and mythology, Humeau imagined nonhuman species developing rituals to cope with mass death. Works such as The Dancer V (A marine mammal invoking higher spirits) (2020); The Prayer (A marine mammal invoking higher spirits) (2019); and The Dead (A drifting, dying marine mammal) (2019) take the form of ambiguous zoological archetypes whose large-scale bodies rest between life and death.

Their synthetic skin with tones uncannily close to decaying corpses, their voluptuous shapes registering highly choreographic gestures. Her practice has been described as Frankensteinian—mostly for its giving form and voice to beings that hover on the edge of existence. Humeau is renowned for having scientifically and speculatively reconstructed the voices of extinct species through sculptural incarnation and sonic spectral animation. For her MA at the Royal College of Art, London she collaborated with paleontologists, zoologists and radiologists to model the vocal tracts of a mammoth, a walking whale, and a giant prehistoric pig. Humeau insists her worlds are not fictions, but expansions of actual mysteries into what-if terrains—an attitude foundational to the Gothic imagination.

She has also often experimented with botanical forms. For Energy Flows (2022) at CLEARING, New York she created a poetic speculation of vegetal drawings and sculptural specimens of plant-based resins, thermochromic pigments, soil particles and beeswax, among other organic materials, but also synthetic resins, marble dust, and glass particles. This body of work marked a decisive shift in Humeau’s material language, towards more alchemical and materially dense processes that look at ancient forms of knowledge rooted in ecological attunement and in the belief—common across many non-European cosmologies—that plants, humans, and animals share a connection to a divine order.

Humeau has described this shift in her practice as an attempt to face the lack of a universal language to express collective grief over the death of many, and the trauma of the seemingly uncontrollable trajectory of climate destruction. One important source for the artist is John Koenig’s Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows (2021) and many of her recent works, including this series, revolve around the commemoration of emotions that humans no longer know how to name, or for which they don’t have names for yet.

In The Forest and the EcoGothic (2020), Elisabeth Parker writes that even if we do not consciously and individually mourn the dwindling of ecosystems from our daily lives, we subconsciously and collectively grieve the loss of these environments, as well as the loss of awe of such sites that traditionally represent the subconscious. She quotes critic Robert Pogue Harrison to insist that so much of the human imagination has projected itself into these sites that when we lose a forest (or any other “landscape of fear”) we’re also losing the great strongholds of cultural memory and creativity.

As we come to realise that the environments traditionally associated with the unknown and irrationality—forests, swamps, caves, abyssal zones, mountainous terrains, arctic worlds—are now subject to accelerated mapping, extraction, and erosion, what happens to our repositories for subconscious expression? Their disappearance entails not only ecological loss and future extinction, but also profound psychological depletion. Once again, the damage ultimately returns to us.

I believe, therefore, that a parallel dimension of the ecoGothic arises from the effort of allowing space for environmental darkness, re-enchanting and re-opacizating Nature (now intended as everything around and within us). As Parker writes, through the ecoGothic, we can experience Nature more immersively: overwhelmed, unconfident, even afraid, but more in touch with our trans-corporeal existences.

Pushing the visual language of Modern science toward saturation, excess, and illegibility, Joey Holder mocks the illusion that knowledge can be all-encompassing. Her installations often take over the whole space, floor included, mixing moving image, intense lighting and wallpapers articulated in AI-generated diagrams and infographics. Holder feeds the neural networks she employs with atlases and encyclopaedias, only to subvert the logic of taxonomy and allow the weird to unravel in all its potential, often accompanying her installations with dedicated websites that further amplify the artist’s investigations.

On multiple occasions, Holder has generated cyber synthetic underworlds of oddities in which technology serves to complexify, generating more data than it can be humanly processed and producing images that evade identification, classification, and subsequent commodification, thus escaping, or even hacking, technological surveillance and data extraction. Cryptid (2023) looked at the planktonic universe of marine creatures such as viruses, bacteria, and embryos, which constitute the basis of planetary life, yet remains profoundly understudied.

Her immersive installation layered laboratory footage of plankton with AI-generated data streams and creatures described in cryptozoology forums and conspiracy sites. In this interdimensional zone, between scientific observation and speculative mythmaking, images themselves behave like living organisms: multiplying, mutating, slipping out of focus.

Abyssal Seeker (2021) revealed the ocean as a vast archive of chthonic beings that outstrip both human perception and scientific capture. It staged a slow descent into an unnamed ocean where hybrid invertebrates drift as shadows through digital abysses. More recently, The Woosphere (ongoing) is set in a psychedelic digital space shaped by misinformation, quantum folklore, and conspiratorial thought. The work unfolds through AI-generated characters on an interactive website—a philosopher, an alien, a golem, a brain organoid, a priest—appearing as CGI talking heads and chatbots.

These function as oracles of fragmented and entropic epistemologies, each performing broken logics and personifying a broad range of beliefs on what constitutes life, human and non. Interestingly, the work unfolds as a reinterpretation of 20th-century beliefs around the evolution of consciousness, mostly centred on the prediction that everything would be united into a collective consciousness.

The early rise of the internet, seen as a global network connecting thought, further emphasised such speculations, but The Woosphere is set in the contemporaneity, where the effects of the internet and technological advancement proved rather different. Between the nonsense and the schizophrenic, here digital information infrastructure produces not shared understanding, but mutually exclusive and isolating realities. Holder’s chatbots are responsive to questions, and they also interact with one another.

They debate and generate new knowledge out of fragmented subjectivities (the artist told me that her same PhD may be partly authored by these characters!). On the one hand, this work exposes a contemporary digital condition of terrifying sociopolitical implications; on the other, it probes an understanding of interdependency as fragmented and polyphonic, rather than unified, trying to test whatever we could learn from chaos.

If technology can help stimulate darker representations of Nature, the risk is that it may also further detach us from its material exhaustion, or at least dematerialise the notion of interdependence to a point of abstraction. Furthermore, the same strategic opacity of technological governance is a thorny terrain in its own right—one that is also shaping contemporary practices of Gothic undertones, and that may well demand a future inquiry within this series.