Interview by Agata Kik

Multimedia artist Kristin McIver dives deep into the digital seas to explore environmental emergencies and the epistemological crisis of the XXI century and brings to the fore the politics hidden behind the wall of the World Wide Web too. Her most recent solo exhibition, Impressions, is preoccupied with the distinct effects of global warming in the different places of viewer experience. McIver looks into climate change by successively using water, fire and earth as focal elements to work with.

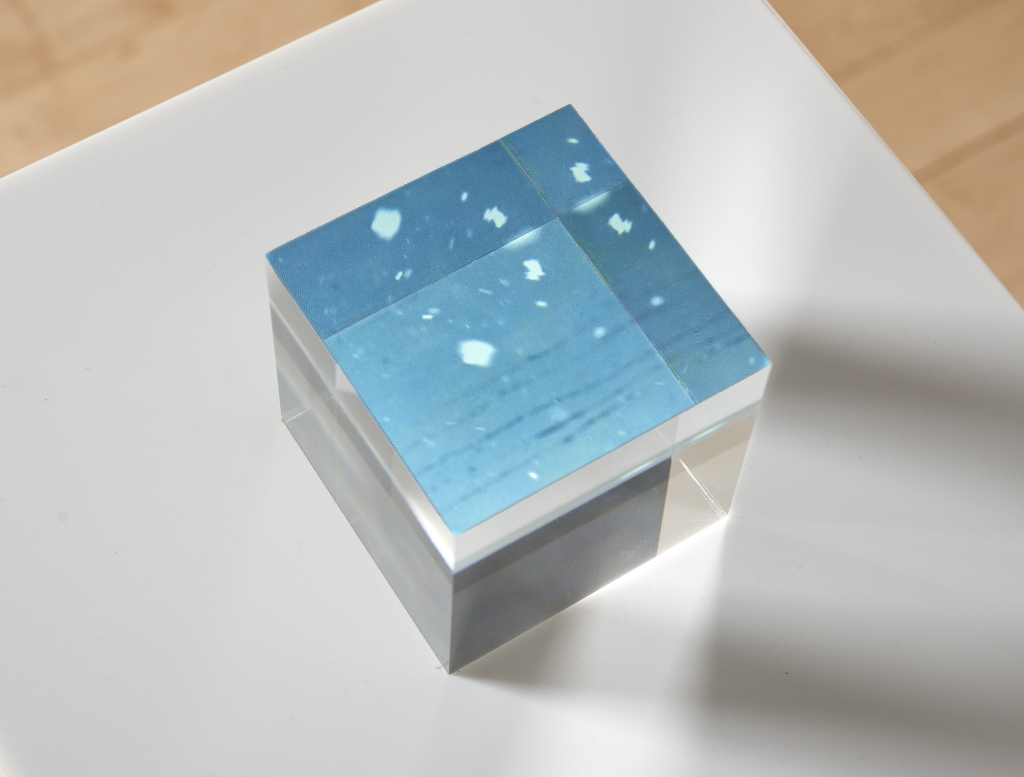

Beyond the physical environment, McIver plays with contemporary perception and representation of data among the population, whose majority’s knowledge depends on the digital flows of information. Water, for example, simultaneously opens up the discussion on rising sea levels and online data streams.

In contrast, accumulative water memory links the past’s linearity of history-making to the present multidimensional moment when time is automatically archived, preserved into eternity and immediately available anytime, anywhere to anyone with Internet access.

McIver questions what we know and how we understand it. Her works uncover the invisible workings behind what we see on the screen. She points to online news, whose comparisons or statistics are easily manipulated by computer algorithms driven by social control and capital gain.

The bare bed of the digital depth is hardly visible to the public, as the surface of the screen is interfered with and influenced by the pre-engineered scenarios of the user experience, which like ripples on the water surface, block one from getting straight down to the bottom of what the real matter is. She gives form to the invisible to help us understand what it means to be part of the big data universe.

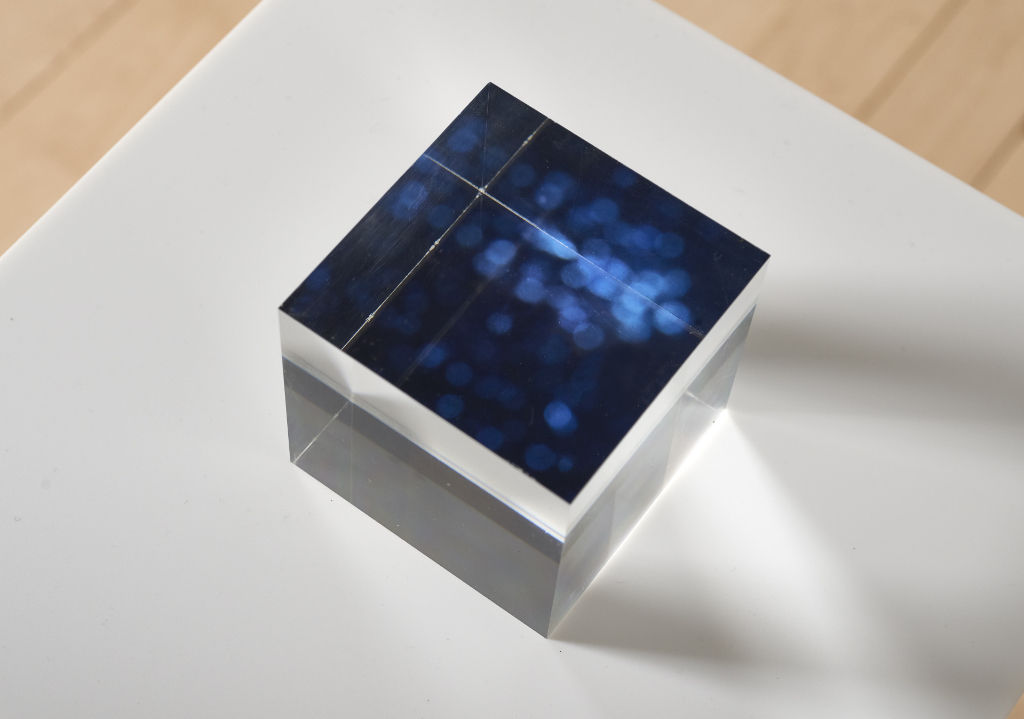

The Selfie Project, a series of paintings, sound and mixed media installations, attempts to decipher the Face Recognition Data and translate the digital into physical and perceptible forms. Data Portrait series, on the other hand, is an experiment to crack algorithmic codes onto acrylic paintings. Innocent as it seems on the surface, these pixelated configurations of different colours and shapes are the source of serious social problems, for instance, when used in law enforcement processes.

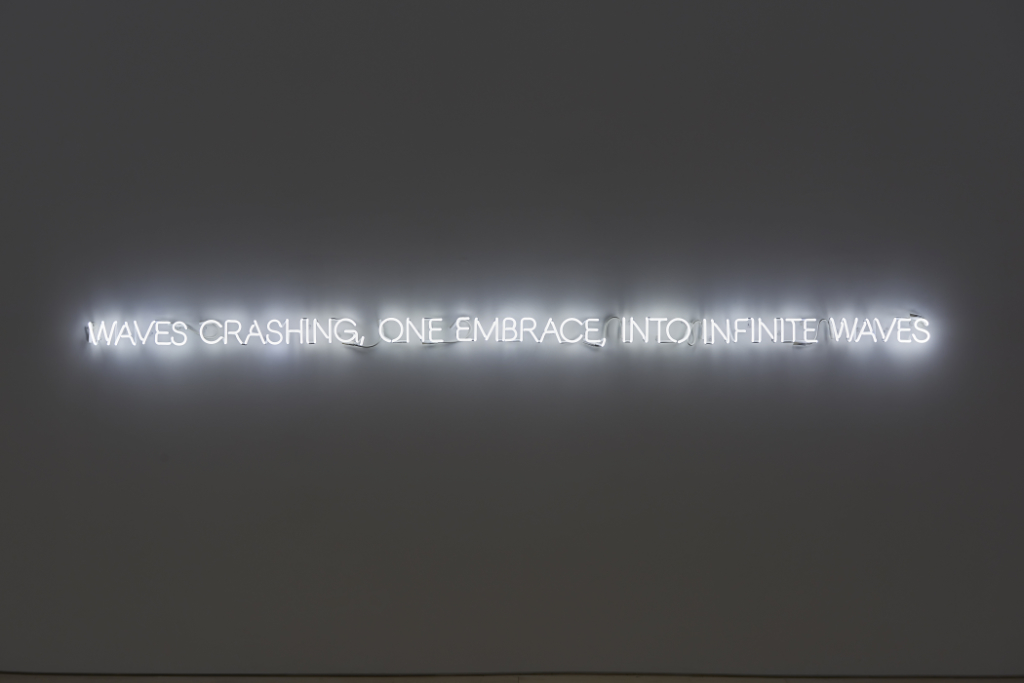

Not only does Kristin McIver give physical form to algorithmic utterances of the computer, but she sculpturally solidifies human language too. In This Beautiful Day, words of a monumental neon sign McIver reflects on the indigenous culture and multiple natives to the land languages that have already become extinct.

The heavy structure of this bright phrase is like a gate to the rich culture of the indigenous people and the feeling of responsibility they have for their land. Perhaps something that the contemporary human does not understand anymore when anywhere can belong to anyone at any time.

In your latest exhibition, Impression at Jane Lombard Gallery, you explore the theme of post-truth in the context of climate change. It is your first solo exhibition in New York. Could you please reflect on the situatedness of this show and how it opens up a discussion that is especially pertinent to the city, along whose coast the sea levels have been rapidly rising over the last decades?

New York has seen higher temperatures, increased precipitation and rising sea levels, placing it at increased risk of flooding, as evidenced by storms in recent years. Alongside the perceptible undeniability of such events, the statistics, data and language surrounding climate add another layer of perceptibility, one that is easily manipulated by algorithms and agendas.

One whose agenda favours climate reform may illuminate a specific timeframe to demonstrate the earth’s warming effects, and one with fossil fuel agendas may highlight a shorter timeframe that doesn’t show warming trends over time.

The language framing these analyses deliberately alter perception, with phrases such as ‘alarmist’, ‘hysterical’, and ‘climate cult’ sitting in contrast to ‘urgent’, ‘climate emergency’, and ‘existential crisis’. As our collective physical experience of the natural world is lessened in favour of the digital, collective thought becomes more susceptible to words and images on screens. The ‘truth’ around the environment is malleable and fluid, like water.

Could you describe how you think with water to enter the discourse on the digital realm, social media in particular, and how the fluidity of matter applies to and influences existence on / and offline?

Water carries in its molecules the earth’s history and knowledge. The same matter has existed, changing forms as it cycles through the earth, river, and sky since the dawn of time. Through each of its different states, water reveals its molecular make-up. Information historically flowed to generations through the spoken word, evolving through retelling, the source unknown.

It’s only in recent centuries that information has been immortalised in printed form and now as binary data; humankind’s collective knowledge is now held in data banks controlled by corporations. Information flows through digital channels like water through crevices, finding the path of least resistance to eager consumers.

Knowledge is served via algorithmic formulas and driven by commercial and political agendas to individuals who have already expressed a particular interest or opinion. The digital ‘crevices’ through which data flows on social media platforms are pre-defined through keywords and hashtags, likes and follows. This reduces the pathways to new information, or a chance discovery, resulting in an increased polarisation of ideals.

Water reflects one’s face, just like social media companies detect it through facial recognition techniques. The Selfie Project, which you worked on in the past, tried to untangle the complexities between our online identity and surveillance. Could you please explain more about this work and share with us what you have found throughout its process?

Still water acts as a mirror, yet even a minor disturbance on its surface creates an abstracted, distorted representation, exposing the matter as molecules bound together into a liquid state. Similarly, a digital photograph is a representation comprised of pixels bound together to form an image of a person.

However, beneath the visible ‘perceptible’, the layer is encoded data such as location and device information, as well as face recognition data, a string of numbers that makes little sense to a human but is perceptible by a computer algorithm to detect and identify a face with apparently 97% accuracy.

This makes it comparable to DNA identification, and it is used as such. This is problematic, as the largest database of ‘faceprint’ data is owned and traded by a corporate entity to state entities. Uploading a Selfie to Facebook unwittingly places one subject to surveillance and tracking – many of the Capitol rioters in Washington D.C. this year were identified through face recognition technology.

A few years ago, I created The Selfie Project, a series of paintings, sound and mixed media installations which transcode this Face Recognition Data into visual, perceptible form. Thus exposing this hidden layer of information and replacing a pixelated representation with an algorithmic representation.

How do you jump between digital and physical landscapes? What does happen when we translate the virtual into matter and flesh? How does one negotiate between the boundaries of the real and the virtual, permanent and transitory, human-made and natural? Could you share some of your insights behind your work on the Data Portraits series?

Each digital representation of a physical object has been captured through a lens, transformed into pixels via an algorithmic formula, transferred to the cloud, and delivered via calculated algorithms to a viewer as they scroll their screen. Along each step of this process, the image picks up units of metadata. Each image essentially carries layers of hidden information, detailing its history, footprint and verification of its existence. I often liken data’s instructional codification with DNA.

This comparison is demonstrated most clearly with Face Recognition Data; in the Data Portraits series, I asked different subjects to send me their Face Recognition Data from Facebook, which I then reinterpreted visually into colourful abstract paintings. In one case, twin subjects produced starkly varied visual results, raising into question the accuracy of these Face Recognition algorithms.

Further research led me to studies that uncovered implicit bias built into these algorithms due to the large number of white college students used as test subjects in their development phase. This inaccurate representation of the population has meant that disproportionate numbers of people of colour are misidentified by Face Recognition algorithms, an inherent social problem when considering face recognition in law enforcement.

What does your work reveal about the simultaneous multidimensionality of the contemporary moment and how it can deceive human understanding?

Human culture has traditionally been passed on through the spoken word, then books, and film. The narrative of knowledge has generally been linear. We are used to stories, chapters, timelines, and series. In the contemporary moment, when most of the world’s knowledge is stored in databases, its accessibility is infinite and instantaneous.

Our news feeds are an amalgamation of incongruous pieces of information threaded together by algorithms into an artificial narrative. My works attempt to expose this link between data and narrative by disrupting traditional storytelling methods and allowing the algorithms to become both author and artist.

Your work This Beautiful Day came about through your work with indigenous communities in their natural environment. What has been your experience of multiculturalism and human belonging to specific physical coordinates?

The work is about language and how that is tied to a particular location. Within mountainous British Columbia, where the work was created and still resides, there were 50 different languages, each geographically independent. Only a handful of active languages remain, with the few remaining speakers racing to document and preserve these languages in written form.

The Coast Salish people travelled by canoe, so the water was integral to the flow and transfer of knowledge, language and multiculturalism. As communities moved, traded, and expanded, each community shared a common respect for the environment over which they considered themselves custodians. Being relatively localised presents an immediate relationship with an environment.

Today, the ability to access any location on the planet (either physically or virtually) breeds a disconnect with the earth, some sense that we are above the natural systems rather than a part of it. The pandemic outbreak has been a stark reminder that we are indeed just a small component within the cycle of the natural world.

Your art practice incorporates various media, material and digital. What is your reasoning behind the choice of different forms? What does your studio work look like? Do you tend to find your ideas through affective encounters and being in contact with materials, or does your work start with virtual research and reasoning?

My medium is essentially ideas. The works begin with philosophical inquiries and are transformed into physical or digital form – or both, through filtering – but the finished artworks operate as intellectual prompts for the viewer.

The work Sitting Piece, an empty chair facing a neon sign stating, ‘Sometimes I turn it on and sit there looking at it’, invites the viewer to become a part of the artwork through their action of sitting. The medium listing for this work is ‘neon, chair, viewer’.

This Beautiful Day incorporates ‘a beautiful day’ in the listed media. Sometimes my studio walls and floors are covered in ideas, sketches, and words; other times, it’s just me sitting in an empty room on my computer, and often the space is transformed into an immersive installation. Recently I was working for a week ‘underwater’ inside a video installation projected onto the studio windows to the street.

Many of your works incorporate language and words-shaped neon lights. How do you combine formal and linguistic communication in your works? Could you share your thoughts on the physicality of language and its activist potential?

Language in its written form is simply a sign which represents an idea. I tend to highlight that by subverting meanings and highlighting dualities in language.

Transferring a word into a physical object such as neon – glass, gas and electric current – it becomes a pure embodiment of form and physics, which activates the space around it. We have seen in recent months, for example, when Donald Trump ‘apparently or not’ incited the riots at the Capitol just how much words matter in terms of activation.

This event highlighted the fluidity of meaning as both parties argued in-depth the possible interpretations of the former president’s statement. A word, removed from its original context, can come to represent an entirely alternative concept, but much of that interpretation falls on the viewer’s subjectivity and prejudice.

What is the chief enemy of creativity?

Capital.

You couldn’t live without…

The natural environment. It’s what grounds me, sustains me, and calms me. It reminds me who I am that I am just one small element within a bigger system. The urban environment, constructed on financial interests and big data, is a simulation. It brings us back to the Coast Salish people, whose existence for thousands of years never sought alternate futures, commercial agendas, or capitalistic ideals. Each interaction with the environment existed as a respectful gesture. Thankful, truthful, symbiotic, sustainable.