Text by David Rollinson

It is difficult to think of a more intimate creative prosthesis than a laptop. Its innumerable functions and impeccable memory, around which we engage in a mutualism of daily regulation. The machine holds our ideas and executes them, with its capacity for limitless translation. But as the dunes of machine learning models sweep around us, it is ideation that becomes increasingly automated. This totalises an already unstable domain as algorithm, dissolving the ground at the fault lines of authorship.

Singular authorship is a long-fossilised concept. Here, the quicksand is the spread of singular narrative. With a growing pedagogical lexicon when referring to computer protocols, one hopes for a broadening realisation that models are not the only devices being trained.

To uncover what is at stake, I call up my fellow alumni from Goldsmiths University’s Digital Arts Computing programme. The degree course centres investigative hybridity and practices of digital kintsugi: breaking and retrofitting technologies to fuse artistic principles with technical experimentalism. Such critical orientations to bleeding-edge technologies are requisite in fostering the potential of change – shifting the narrative away from western productive extractivism toward a site where cloaked sentiments and vested interests are revealed, contested and refactored.

Digital Arts Computing practices are erected in the arable between well-rooted fine arts and computer science departments, inverting traditional mediums to (de)construct the moment, charting the annular stream between culture and politics. Using the work of four artists as a springboard, I attempt to disclose the danger zones on our map and discuss how technical experimental arts practice responds.

Our maiden dive lands us between the two bowed sonic strata of ‘Echoes’, by Vendela Haakonsen. Her multi-layered installation, parenthetical in construction and temporality, seeks to unfasten an audience from their surrounding gallery. The sculptural punctuation points construct a negative space beckoning bodies, requesting moments of grounding and reflection. Loudspeakers fitted into the centre of each chequered facet emit on-the-fly generative soundscapes, cutting whisper vocals with synthesis inspired by urban phenomena. The sound library is pulled from the artists’ field recordings, where sounds of broken digital fixtures and machinery were collected and recreated in the open-source programming language, PureData.

Through this, Haakonsen archives damaged and defective systems of infrastructure, augmenting memory and perception by imaginatively recreating, looping and elongating moments of glitch. In an era of proliferating automation by the promise of convenience, the citizen is increasingly expected to navigate such new digitised cartographies and vocabularies that delimit usage to its most concise legible form.

Behavioural edge cases are unacceptable to a teleology of optimisation, resulting in anaesthetised, ‘smooth’ interface reliant upon a user genealogy that standardises accessibility needs. Alternate modes of engagement are not accounted for, erasing lived experience that produces non-standard interface requirements. Therein, moments of glitch or defectiveness become a revelation of internal mechanisms and media, discrediting monolithic smoothness and hinting at undiscovered or unrealised modes of use.

Haakonsen widens these moments with sounds algorithmically bent out of shape – waxing, waning and winding round one’s ears. Parameters are toyed with to provoke the body’s relationship to technological tactility. The blank, smooth canvas of PureData is a potent site to do so – an open-source dataflow programming language, PureData is both graphical user interface and open system. Users can ‘patch’ together code modules to create networks of data flow and control.

On opening, the program greets the user with the restrained, boundless white of its’ command interface – a mystifying introduction that coaxes absorbed activity over theory. Its’ interface is unyielding because the affordances of its vacancy are for creativity over productivity.

Open Source makes multiple-authorship requisite for such tools to evolve – with common stakes in a particular outcome, the creative community encourages greater transparency and stability instead of commercial obscurity. For Haakonsen, this process is integral to the project’s concept; the unlimited permutations of past and future within both software, society and the senses that never reach denouement, where new realities may be sown.

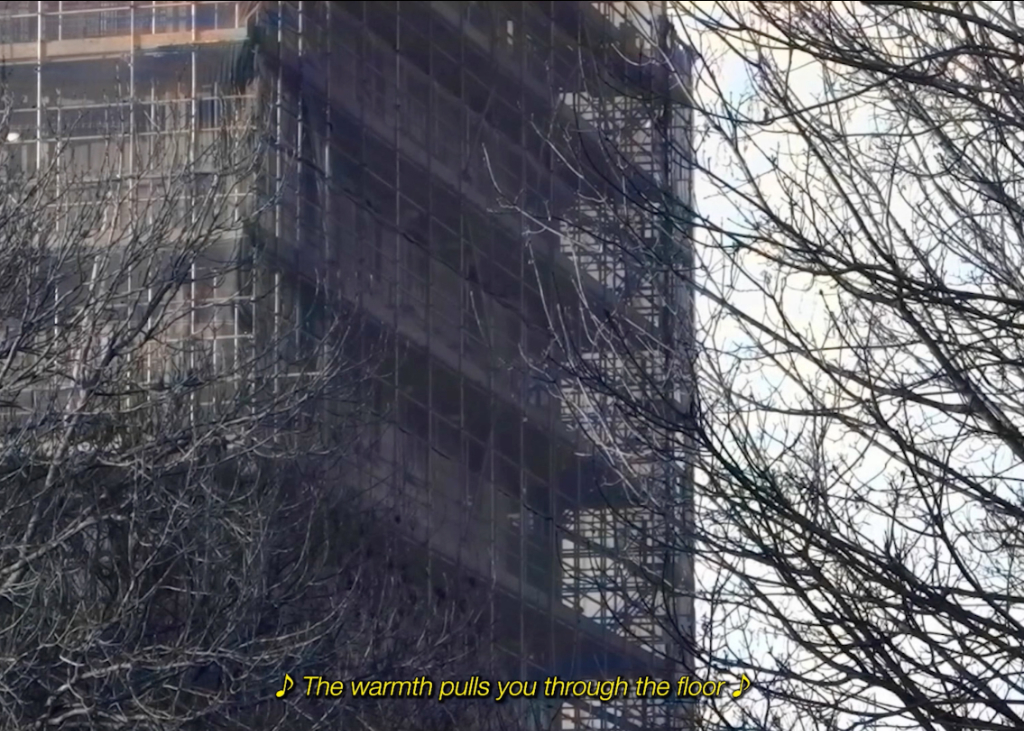

Turning us from temporal dilation to diorama, our next artist Noah Griffin presents an immersive anthology of the city as a somatic artefact. Comprising narrative film, sculpture, audio production and performance, ‘Bleeding into the World’ offers a window into a patient undergoing a medical procedure of voluntary agnosia. Griffin contrasts the patient’s internal thoughts, read as captions, with cinematic expanses of the cityscape, spirating bodies and angular metropolitan structures – their gaze often elevated upward, building foundations debased and out of view. As such, the patient is decorporealised – their mind’s eye and their imposing observations decoupled, whilst whirring static punctuates ambience with the regularity of a ventilation device.

Originally shot in black and white, Griffin uses a deep learning image recolour tool to stitch colour back onto the footage as a kind of machinic synesthesia. The colours are reactive to audio and vibrations inside the space, where vibrational intensity causes chromatic fidelity to ebb. The result is rendered shifting, uncanny, and heterotopic whilst remaining discernibly metropolitan. Similarly, in the music performance variation of the work, Griffin uses a stable diffusion tool to generate sonic samples. The tool is a variation on prompted diffusion image generation that is trained on music spectrograms to generate and interpolate samples. Lyrical verse is razed or blurred by algorithmic reconstruction, depersonalised as the film’s subject.

Griffin’s choice to integrate machine learning technologies into every sensation is deliberate and subtly provocative. The proliferation of machine learning toolsets means their increasing embedment into the contemporary day-to-day. Representative of massive seed funding, large-model tools for automated choice-making and media generation are now quickly normalised by promises of early adopter rewards.

The sheen of personal productivity improvement is an up-sell which belies the ghost labour beneath seemingly automagic processes: model efficacy is contingent upon crowd work. Thousands of underpaid workers in the global south perform microtasks as daily employment and data labelling, often under precarious contracts that offer no professional mobility. Explicit content must first get filtered out by a person.

Beneath tech giants, this is performed by outliers beyond official labour markets, such as illegitimate migrants, refugees and convicts, and by formerly privileged workers deskilled by the reducible attrition of hyper-production. The cities of people that make up such forces of labour are implicated inside Griffin’s city proper. Urban infrastructure is the conduit for the digital, operating as an organism that functions supposedly to the benefit of us all – its cyclical enterprise made ordinary to contemporary visual culture.

In our perennial crisis that holds bodies as collateral, Griffin’s heterotopia is an unspoken inversion that creates nostalgia for another, imagined present, a subtle departure that questions the often-forgotten urban relief space that holds its most numerous and constitutive voices suppressed.

Materialised as metallic spectre of such a present, Theo Goff presents a poised spatial intervention that towers over its audience. Angled screens cast choreographic film outward on each wing – the dance performer Isabella Pinto buffers and disorders as a real-time pose detection system interprets and matches her movements. Alongside, Goff cuts an audio track of soliloquies from two artist friends, assembling a lucid conversation between them. Despite the two being strangers to one another, the recordings suggest a unity in one another’s introspection and ideas of love in a ‘shabby landscape’.

Using materials reminiscent of datacenter server racks, the perforated metal sidings of ‘Scene Outfit Output’ by Goff expose messy and unfinished internals. Transporting us beyond the sleek veneer of technical infrastructure, the audience peers into its true vernacular of tangled cables, circuit boards and heat.

Technologies that both facilitate remote work and provide the computational scale necessary for massive data scraping and model training are a collision of older infrastructures of dirty labour and material extractivism: international data transmissions conducted by submarine cables trace the paths of maritime empire expansion; the use of cobalt in alloys and cathodes for battery and data-storage technology is enabled and perpetuated by culturally erosive labour practices of exploitative mining firms in Central Africa and Oceania.

The distribution of The Cloud and its numerous stakeholders co-produce its image of ephemera and convenience – one that collapses matter into gossamer, distant or intangible archives. However, data is just as much patterns of user activity as it is representational media. Mystification of The Cloud’s heart, the datacenter, is conducive to the extractivist, surveillant informatics of domination within. Consumer amnesia is the final shoring up of product optics that never makes dispute despite the glut of information in simple reach.

Cloud interface crowns the user sovereignty of their own virtual data real estate, but it is the entropic rapidity of data ubiquity that destroys spatiality in the present. Scene, Outfit, Output fends off this future of simultaneity by physicalising the cloud as a mnemonic counter-monument. Historically the monumental – belonging to a genre of visual rhetoric that primarily exercises spatiality – moors, legitimises and preserves ‘official’ civic memory in reaction to unfixed futures.

Goff counters this in our present ‘age of rubble’ that forecloses futures in a blight of simultaneity with a monumentalisation of that which constitutes such (lack of) futurity. As a result, Scene, Outfit, Output becomes a paradoxical rallying cry. The stabilisation of infinite read/write speeds as geologic, spatialised time perhaps holds futurity ajar enough for it to be (re)written, reminding us that there is agency, still, within the localised domains of skin and hardware.

In a conscious activation of this domain, Tiffany Tang presents All Women You Are Human inside a curtained room. Breaking the shroud, a film of a figure lit in red runs opposite, whilst sanguine eggs cocoon a camera that tracks body presence. Adjacent, chrome instruments – artefacts used in the film – attached to the wall euphemistically gyrate and flash with urgency.

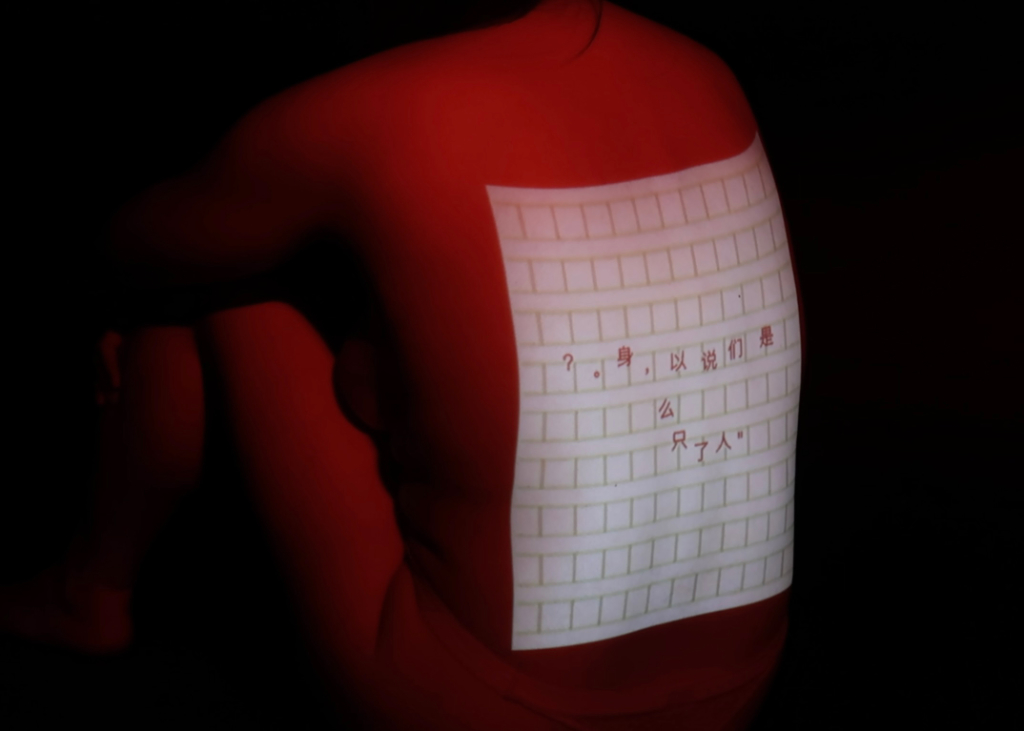

The film’s figure laid laterally and clutching flashing breasts, transmutes as the audience roams the space, stepping closer for the figure to shrink and turn away in dismissal of address. A text interface appears down the figure’s spine that mutates and refracts excerpts of Chinese author Gao Xingjian’s ‘Soul Mountain’. The fictional travelogue was banned for its reproach of Confucianism, but Tang extended its migration by threading it through various fields of neural translation tools, finally rendering it into English subtitles beneath.

Tang immediately implicates the audience inside a spatial interface – the input/output boundary is breached as the work’s systems instantly respond to their new associates without pre-authorisation. A correlation is established between bodies and machines in the space; both are signalled as coded in their servility to distinct configurations based upon their societal, geographical, and political locales.

Moving (metaphorically) inside the machine, it’s clear that heterogeneity reigns as the world is mapped to fit its matrices. The constitution of the world becomes a problem of coding: one that searches for a universal language, subsuming everything as exchangeable in the process. In Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto, she argues that this includes bodies, now apprehended as devices that execute the especially intricate protocol of biology.

Sexuality and reproduction – what lives are, willingly or not, structured against – are flattened into the smooth flow of exchange. The stakes here are dire; the self becomes even more illusory, and domination tactically replicates. In this Turing-complete world, a reverse cannot be found in its binary opposite. Relief of a stable epistemological system is just as stable; those only seeing opposites as impressions become trapped inside a revolving door.

Zooming back out, All Women You Are Human architects a lengthy channel of re-translation, -prediction and -contextualisation of the text, charting ‘Soul Mountain’s shifting gestalt as all the more irresolvable. Tang prompts and re-prompts neural translation tools with the text at varying levels of context – with singular words, then phrases, then whole passages to foster a reciprocity of interpretation. An unseen operator selects these new narrative configurations from a grid of buttons.

The subject of the text becomes pluralised in the mire of jumbled perspectives and model weightings, but nothing political of the machine or body is discarded in the process – there is no inversion/‘relief’ to speak of. All this shifts into view a refraction of material and ideal that simulates but does not adhere to the political dogma of technology – it demonstrates an interruption to the smooth flow of information exchange that can ripple through networks of correspondence.

Closing in on logics bent and misshapen as the reflections in her chrome instruments, Tang’s refractions of technology spin out a strategy through which her audience might seek, recode, and transgress self-concept. We are called upon to trust a different process, one resolute to the cause of broadening a future world.

This sets the basis for my own reasoning for the field of digital art. To reject digital mediums by the argument that they are replete with political and ethical plights is not a strategy. In light of the forces of domination we have explored here, it is understood why a dismissal to integrate these mediums should occur.

Conversely, embracing the lure of smooth false promises announces an untrained eye that becomes set into a blinding vortex of dogmatic perpetuation. In each case, turning away from concern forecloses necessary relationships of instability and dulls an attentiveness requisite to pick through the detritus. Computational understandings can be all too easily captured by the gravity of optimisation – after all, serving this model is often how we survive the interim – but it is the revelatory play of artistic practice that can keep possibility stoked.

One must be diligent in the field – where we position ourselves to act as the balancing weight on our vessel charting hostile waters. But when the stakes are so high, everything hidden must be called into view to realise habitable worlds to come.