Interview by Ed Harrington

Boxcat Studio are unafraid to push the boundaries of what’s possible with their digital design for live shows, artwork, and create experiences. After officially forming six years ago, the collective has gone from strength to strength, creating work for a broad range of artists and projects, constantly striving for unexpected and unique outcomes.

Their work on the Lost Frequencies live tour saw them create a fully real-time show. This achievement demonstrates their dedication to forwarding the progression of digital design for live shows and displaying new realms of possibility within the field. Boxcat Studio have embraced this move from traditional methods to real-time methods as something that is crucial to furthering the future of live visuals. But their best-kept secret lies in their core principle of grounding the conceptualisation of their content in realism for the work to communicate with audience members in a meaningful and relatable way.

With a strong focus on the architectural elements of a space, the team considers everything from the shape, scope, lighting and placement within a performance in order to accentuate the delivery of a live artist’s work, keeping the majority of the concepts for the graphics influenced by real-world things. By creating visual pillars for a show, the team can connect narratives and progressive themes with the visuals to conduct genuinely immersive experiences that are memorable and vivid.

Using real-time animation software such as Notch and other programming tools, Boxcat Studio have explored these techniques to an expansive extent, especially when taking on projects where their visuals come to the centre point. For instance, when working on material for theme-based events at Club Woo and Club SOS, the team utilised software like Unreal Engine to create content for virtual set extensions, creating intensely atmospheric scenes.

Their current live exhibition at Drumsheds, London’s new cultural hub and venue, sees the studio coming into their own as far as their technical prowess and collaborative capabilities go. Having teamed up with Broadwick, Boxcat Studio are using the space – a disused warehouse with a screen equivalent to the size of four double-decker buses – to orchestrate captivating live shows, displaying digital motion sculptures that are customised for each performance, making use of the negative space to provide a realistic and enveloping environment for the audience. They have also given attention to the use of colour, shapes and epic imagery to emphasise elements of the building’s character and measure up to its extraordinary scope.

For those unfamiliar with Boxcat Studio’s work creating bold visuals for live performances and installations, could you describe how you got to where you are now and some of the work you are most proud of?

Alex Wilson: Boxcat originated around eight years ago, initially serving as a platform for purchasing VJ loops. The journey took an exciting turn when I crossed paths with Ollie online. He was seeking custom content for an artist he was tour managing, and our collaboration clicked. Recognising that our combined skills benefited the creative process, we officially established Boxcat Studio six years ago. One standout accomplishment for me is the Lost Frequencies live tour. This project is special because of the significant learning curve in executing a fully real-time show.

You joined forces six years ago. In that time, you have worked with most of the UK dance scene artists. Could you describe the creative process when creating conceptual visuals?

Alex Wilson: Typically, Ollie takes the lead in handling initial ideas and client calls. Once he clearly understands the project requirements, our team collaborates to create a mood board and pitch deck. After the client approves the pitch deck, I step in to manage the project and assign roles accordingly. Our creative process is all about exploration and experimentation. Entering a project with a rigid idea can often result in a less-than-optimal outcome. We thrive on the dynamic nature of our creative approach, allowing room for innovation and unexpected discoveries throughout the process.

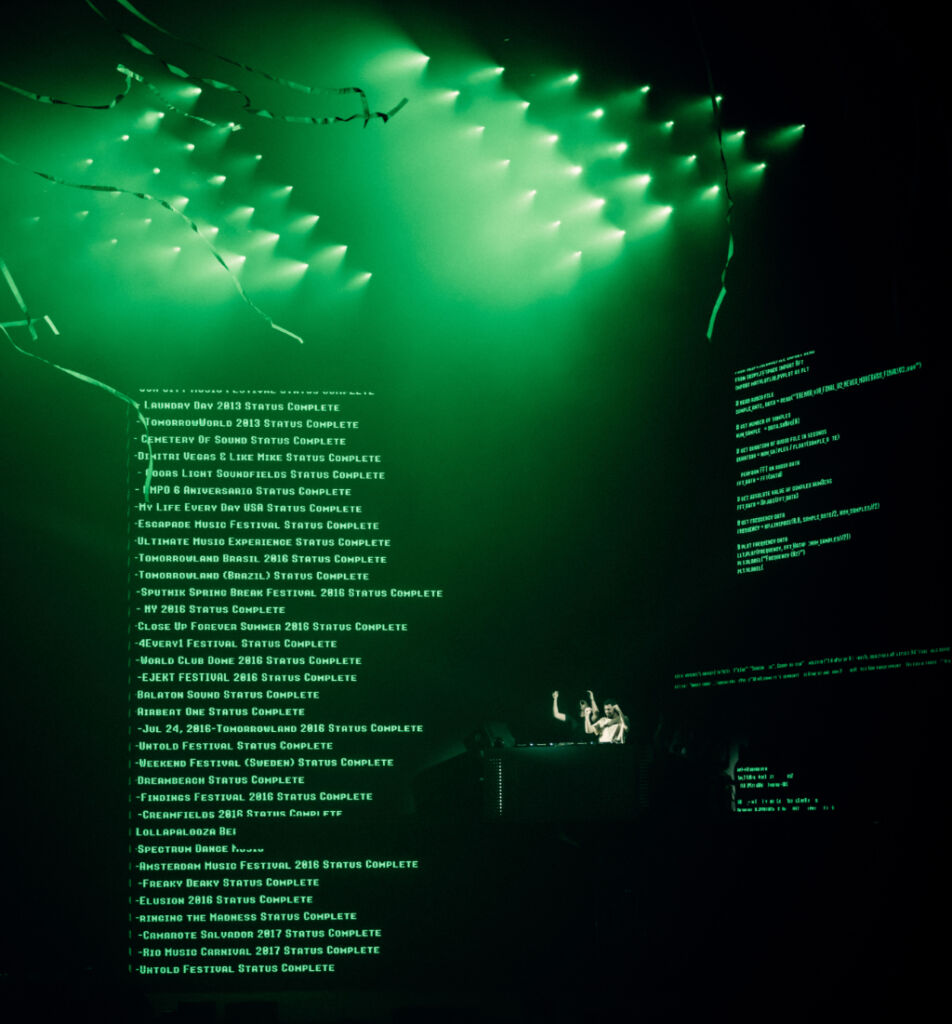

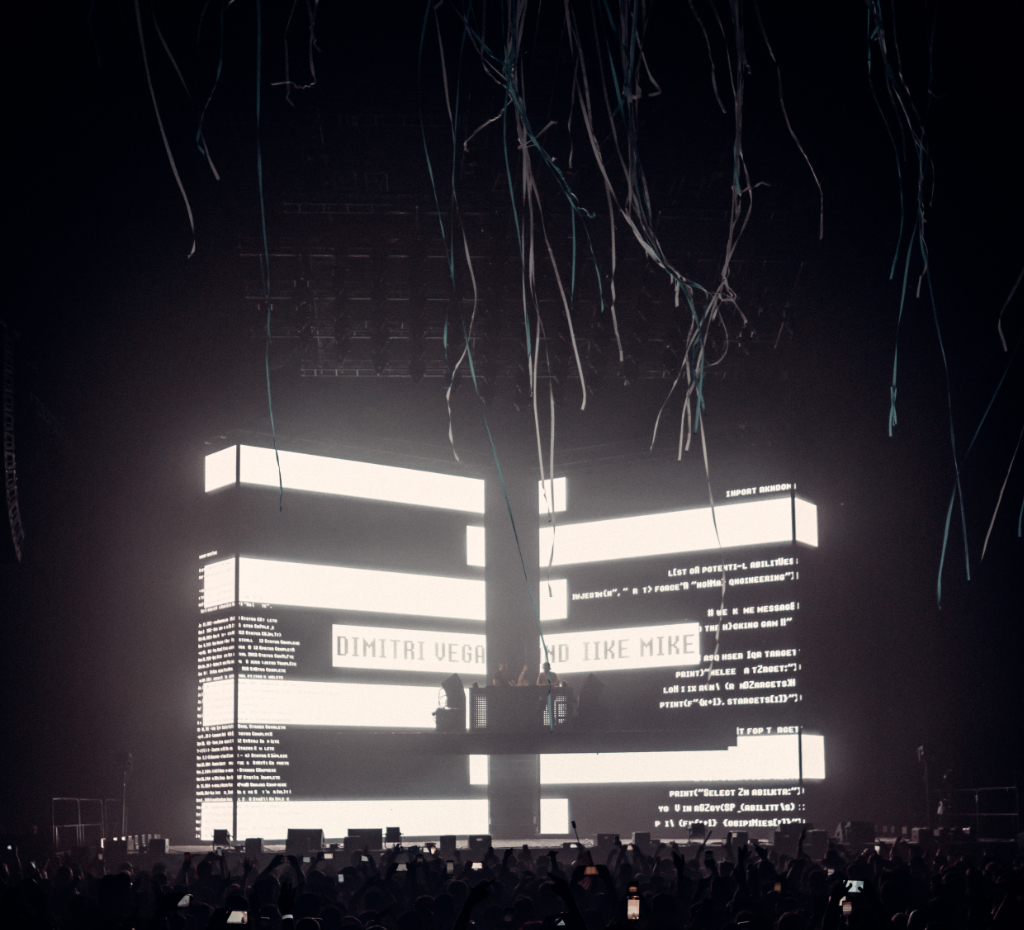

You have worked on visual content for arena concerts, such as Dimitri Vegas and Like Mike, at the OVO Arena Wembley and outdoor music festivals earlier this year. How do these different environments affect your approach to creating visual experiences for them?

Ollie Van Gent: While arena shows present challenges when working with these electronic artists, designing a show that works for all stage types is the biggest challenge. One day, they could be on a crossover festival with a 16:9 screen; the next, they could be on an EDM-style stage with multiple panels of LED in questionable positions. We have also become known for our camera integration within shows, and balancing these cameras while running Notch and Resolume on the fly is where it starts to get fun.

When we work with more live artists, you have more control over your surroundings and production, allowing the show to visually be the same every day. This also allows for you to have more complexity within the visuals and much more track development than something you would see in more of the electronic scene. Even most of the big production electronic shows follow a build-break-drop structure (even when they don’t know it)

Some of the work you have been commissioned to create has given you complete freedom over the artistic approach, for example, the visuals you created for the Club Woo in China. In this work, you used programming and real-time creation tools such as Notch and Unreal Engine to create scenes depicting water, fire and ice. Or when working on the visuals for the Lost Frequencies 2022 live tour, you use Notch FX-created real-time graphics. What is it like making artwork with this type of technology in comparison to more traditional methods of content creation and video playback?

Alex Wilson: Real-time content creation represents a significant leap forward for our industry. It is a substantial advantage to enter programming with a foundational show file and synchronise it with the physical world’s lighting. Real-time rendering serves as a crucial bridge between technical and traditional art forms. The ability to experiment with new ideas and make changes instantly, without waiting hours, days, or weeks for renders to complete, is a game-changer.

You recently unveiled your new digital art installation for the new London-based venue and cultural space Drumsheds, for which you created a series of visuals. The artwork is displayed on a 48 x 4 m screen. What was it like balancing your unique approach with Broadwick’s creative direction while trying to capture the essence of the space you were working with?

Ollie Van Gent: When the call-up came in for Drumsheds, it was an obvious collaboration; we have always looked up to Broadwick as a company that consistently has a solid brand and marketing. From a design standpoint, both companies have a similar aesthetic that we prefer, so coming up with the initial concepts and visual pillars we would work to for the new space came quickly. From then on, we were trusted to run with the ideas and start creating.

How did you use negative space when working in this kind of setting to create emphasis and scope in the shows at Drumsheds, and how do you think this was communicated to audience members?

Alex Wilson: Mastering negative space is paramount in a venue like Drumsheds. The expansive width of the screen introduces a considerable amount of light to the space, potentially overwhelming it. To combat this, we use a range of animated and static alpha masks to strategically break up and rearrange content within the room. This approach offers the flexibility to use the same “clip” multiple times, transforming its appearance each time and helping build a narrative throughout the night.

Who are the main inspirations for your work, and what has driven your desire to create visuals that marry artistic intent with aesthetics in a live scenario?

Alex Wilson: A guiding principle I adhere to is rooted in realism—if an effect or visual can’t be achieved in real life, should it be pursued in the realm of computer graphics? While this rule may not universally apply to every shot or client, it sets our studio apart by emphasising authenticity and pushing the boundaries of what’s achievable in the digital space.

Ollie Van Gent: My style is typically based on architecture with the set extensions we create. I’m fortunate to travel a lot as a big part of my job, which helps me stay inspired by real-life things. As Lexy mentions, even when we go 3D, there has to be a sense of realism; we almost never create something that you wouldn’t see in the real world, including how scenes are built and the lighting and cameras we use.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Olli Van Gent: Time…. Time is usually our biggest enemy. Especially when working with touring artists. As it should, the music comes first, so often, we don’t start building shows until the music is finalised. Of course, we start conversations, create concepts, and prepare as much as we can, but there is often a sweet spot of time when we have to create and render any content we are making ready for production rehearsals / the first show.

You couldn’t live without…

Ollie Van Gent: It sounds very cliché, but the team that we have been growing around us both full-time and freelance. In such a freelance industry, it can be challenging to build a company, but having that team helps get through those creative barriers that block so many creatives. The ability to sit down with another artist and collaborate on creating these digital artworks is key to keeping our quality.