Interview by Eleni Maragkou

A gentle light dances on the wall, softly alternating between shades of blue and yellow. Though initially subtle and imperceptible, the shifts grow in intensity. Serenity gives way to a growing sense of unease. Perception is slippery, subject to trickery from the mind and external stimuli. The lines between repulsion and attraction, fear and pleasure, light and darkness, inner and outer world are thin, porous, and easily permeable. Philip Vermeulen is well aware of this. The work described in a few sentences above is Chasing the Dot, created especially for the artist’s upcoming exhibition at Rijksmuseum Twenthe.

Perennially fascinated by the interplay of light, sound, and movement and how they can be manipulated to create altered states of being, the Hague-based artist produces lofty installations, or ‘hypersculptures’, that explore, stretch, and challenge the boundaries and the limits of experience, allowing access to different realities and states of mind.

Drawing from the lineage of the ZERO movement and the kinetic works of Francois Morellet, Victor Vasarely, and Jesus Rafael Soto, Vermeulen uses light and motion to produce a form of sensory interplay that challenges our perceptions, making us question what we think we see and hear. Otto Piene, co-founder of the ZERO movement, writes in his manifesto, Paths to Paradise: I go to darkness itself, I pierce it with light, I make it transparent, I take its terror from it, I turn it into a volume of power with the breath of life like my own body, and I take smoke so that it can fly. Through works like FlapFlap, BoemBOem and More Moiré, one can see this philosophy in action as the artist guides the viewer on a transformative journey that subverts the initial sensory encounter.

ZERO is an avant-garde movement that formed in the 1950s in response to the pessimism and subjectivity of some strands of post-war abstract art. Turning away from the gestural brushwork of Tachisme and the ambiguous textures of Art Informel, ZERO deploys light, movement, and monochrome surfaces to create artworks that emphasise simplicity, structure, and new forms of spatial and sensory experience.

Since graduating summa cum laude from the ArtScience Interfaculty in 2017, Vermeulen’s work has graced the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, and Zentrum für Internationale Lichtkunst in Unna. He has been nominated for the Volkskrant’s Visual Art Prize, and his installation More Moiré2 earned a nomination in the Best Interactive category in the most prestigious film award in the Netherlands, The Golden Calf.

Opening on June 28 and running until January 5, 2025, the exhibition Chasing the Dot will span seven big spaces of Rijksmuseum Twenthe. This is Vermeulen’s first overview exhibition, and it features the brand new, especially created eponymous work alongside five other expansive installations. To expand the senses and provoke deeper emotional and psychological responses, Vermeulen invites the audience into the realm of the intangible. Ahead of the exhibition’s debut, CLOT spoke with the artist, delving into the thematic underpinnings of his work, his venture into non-kinetic sculptures, and the role of play and immersiveness in his art.

What are the artistic intentions that propel your ongoing creative process? Where do you draw inspiration from?

My artistic intentions are rooted in exploring the boundaries and the limits of what can be experienced through art. Movement, for example, to me, there is nothing more beautiful than the vibrations of a speaker. And it becomes even more pretty if the speaker pushes towards its limits. Suddenly, you do not hear only the sound that it is playing but also the materiality of the different elements of the speaker. Then, as someone engaging with the sound, I automatically become way more focused. Is the speaker going to hold, is it going to break? The speaker’s motion has a form of emotion with different speeds, movements, sounds, and lights. They all somehow move me; their motion influences my feelings. When that happens, I can get extremely excited.

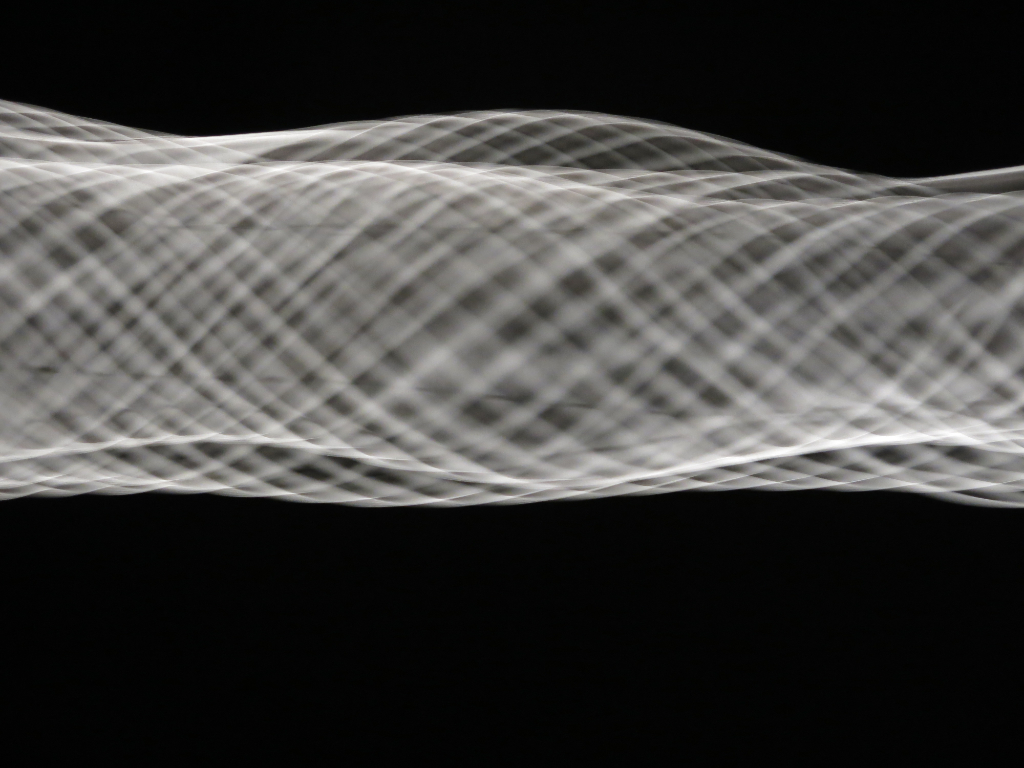

The simple example of the speaker was, for me, a trigger to make machines or an instrument where I have complete control over the speed and can experiment with it. This resulted in my work called FlapFlap, a huge and modified machine. The orange curtain in the high-speed machine can fearfully flap so fast that you start to hear the sound. And you see waves and patterns moving so fast that you’re unsure if they’re standing still.

I have a deep fascination for these contradicting emotions: attraction versus repulsion. Being mesmerised by danger. I would like to be in this tension between rappelling and attractiveness. It feels like stretching out the senses – fading inside of that thing—the different spaces in our heads. I have an intense fascination for emotions and how intangible they are – giving form to the immaterial, painting with light, and seeing sound while hearing light. Does that make sense?

I get my inspiration from playing around, experimenting, mumbling, boredom, and books—art history, media theory, archaeology, children’s books, meditations, yoga, and the adventure of taming the brain. I love painters, movements, and mixing things up in unexpected ways.

Your research continues a lineage of experimental art from the Zero art movement, sound art, kinetic sculptures, and audiovisual arts. How did your interest in these topics emerge?

In retrospect, I wasn’t that interested in museums as a child. What I was interested in and attracted to was always playing with patterns, movement and perception. So, if it directly influenced my senses, I would appreciate it, as in the kinetic works of Francois Morellet, Victor Vasarely, and Vibrations Métalliques by Jesus Rafael Soto. It was never my goal to do art school. I wanted to do the film academy, as I was into documentary films and DIY, experimental shorts. However, my tutors at the film academy recommended that I study arts to have more creative freedom and that I could express myself. Although I still wanted to make films there, I loved painting, writing, and creating sculptures. From the start, the works I started making had a clear theme. I didn’t realise it back then, but I do now when I look back. [1]

Play(fulness) seems to be a leitmotif in your work—can you elaborate on its significance?

For me, making and creating are more about the moment. I don’t allow any analysis while creating new work, as it’s a killer for me—it’s a different process. I want to be in the moment and only look back after finishing the work. John Cage made this nice document (10 Rules for Students) with rules for students, which is helpful—how to get the most out of conservatoria or art school. [2]

It’s great to feed yourself with culture and thinking, but not while creating a new work. If you work that way, the outcome is already fixed, becoming this theoretical puzzle. For some, that’s how they work, but for me, it’s about experimentation and seeing where that takes me. When I start with a new work, the process can be clumsy. I also like to involve my studio team and play together – take a material or a process, explore different routes and see what happens. Let it free, and see what happy accidents might result from it. I let materials and scientific phenomena lead me; I set them free and let them say what they want.

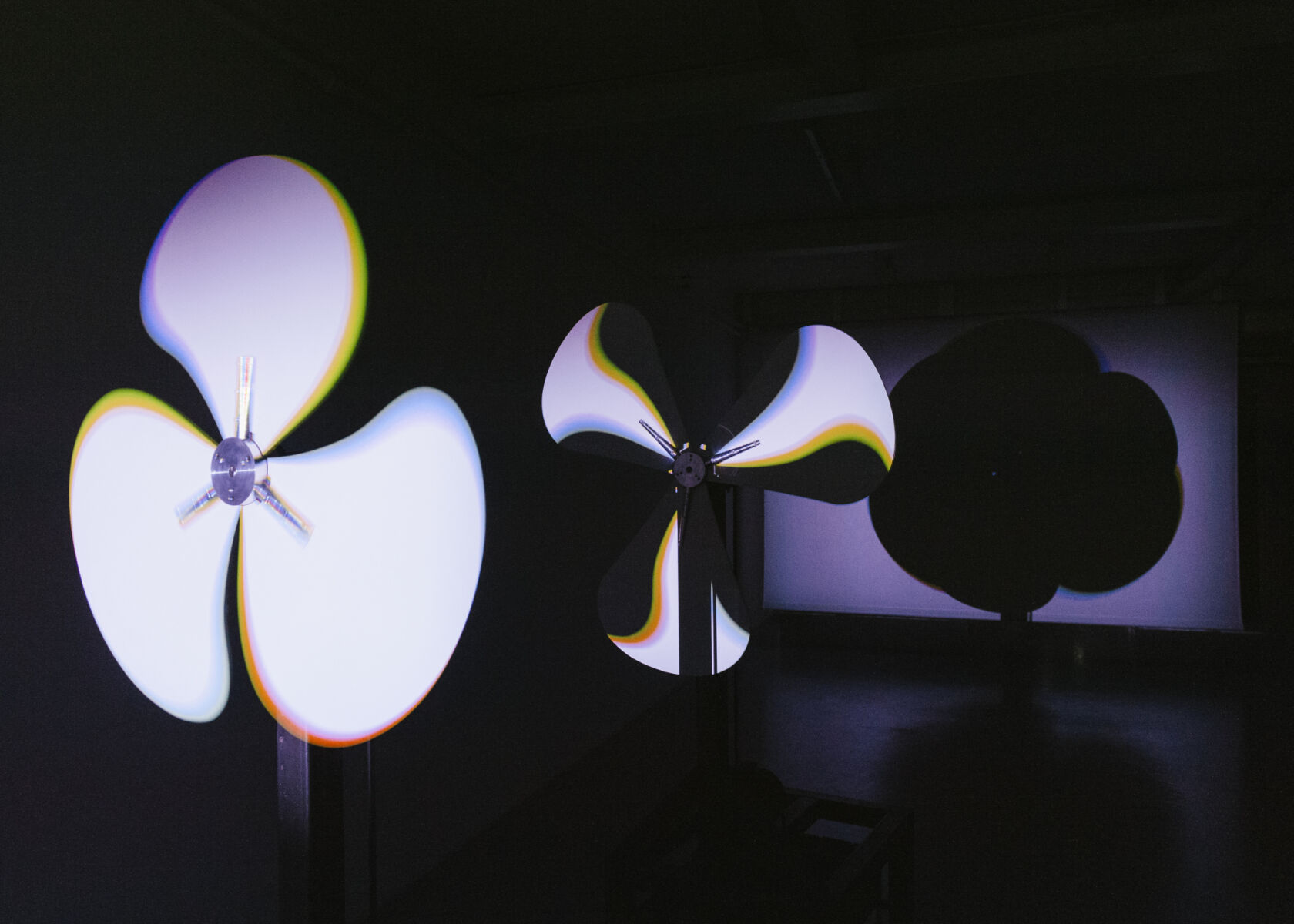

For instance, in Fanfanfan, the phenomenon is simple: there is a DLP projector with a colour-shining white light. By the moment it’s possible to see this colour rainbow, the fanfanfans want to scatter this white light back into colour. It’s very precise. Therefore, it has to be fast and have reasonable control over speed. A happy accident is that sweet spot when they are in sync, and there’s this range of colour and sound – a clear tone; I never thought that would happen, but it’s there. It’s nice to think of kinetic artworks as instruments. I build them while learning how to play.

They move and make a sound, so shifting from the classical art sense of the object towards an instrument suddenly gives one a different language to use, a different toolbox. And there is nothing more fun than playing an instrument. I studied Fine Arts at a more traditional arts school, the ArtScience Interfaculty, part of the Royal Conservatory in The Hague. This was a significant time for me.

In your space-filling kinetic installations, which you call ‘hypersculptures’, you explore and alter the foundations of human perception. Why did you choose this as your medium, and how did your fascination with elusive, fleeting, or illusory phenomena begin?

My choice of medium for creating space-filling kinetic installations, or ‘hypersculptures’, stems from a deep-rooted fascination with the interplay of light, sound, and movement and their collective impact on human perception. This fascination began already during my childhood. My mom always tells the story that I was conversing with the pigeons when I had Paratyfus, with a high-pitched fever. I would live in my little world. For example, as a kid, I loved hiding in the closet, underneath the cloth, with a Walkman blasting rave music from a local radio station, and then I would wonder how the light would be in those environments.

During studies and early artistic experiments, I explored how physical phenomena could be manipulated to create altered states of being. It was never a conscious choice to work with the installation medium, but it naturally fits what interests me. This can be traced back to my personal experience with addiction and an inherent curiosity about different states of mind. Having had a history of intense and challenging personal experiences, I became intrigued by how external stimuli could profoundly alter one’s perception of reality. Therefore, I’d say the works also have a strong autobiographical element; although not immediately visible on the surface, it’s definitely there.

At its core, my hypersculptures allow me to create experiences that captivate the senses and evoke more profound psychological and emotional responses, inviting the audience to explore new dimensions of perception and reality.

Your artworks deal with the disruption of the border between mind and matter. What experiences do you want (your audience) to access through them? What is the significance of such experiences?

My works indeed focus on experiences—these are very individual and differ per person, but they are typically experienced collectively. I aim to blur the boundaries between the inner and outer worlds. Installations like BoemBOem and More Moiré are created to take viewers from initial tension and fear to a state of awe and enjoyment, thereby offering a transgressive experience that challenges and expands their usual perception.

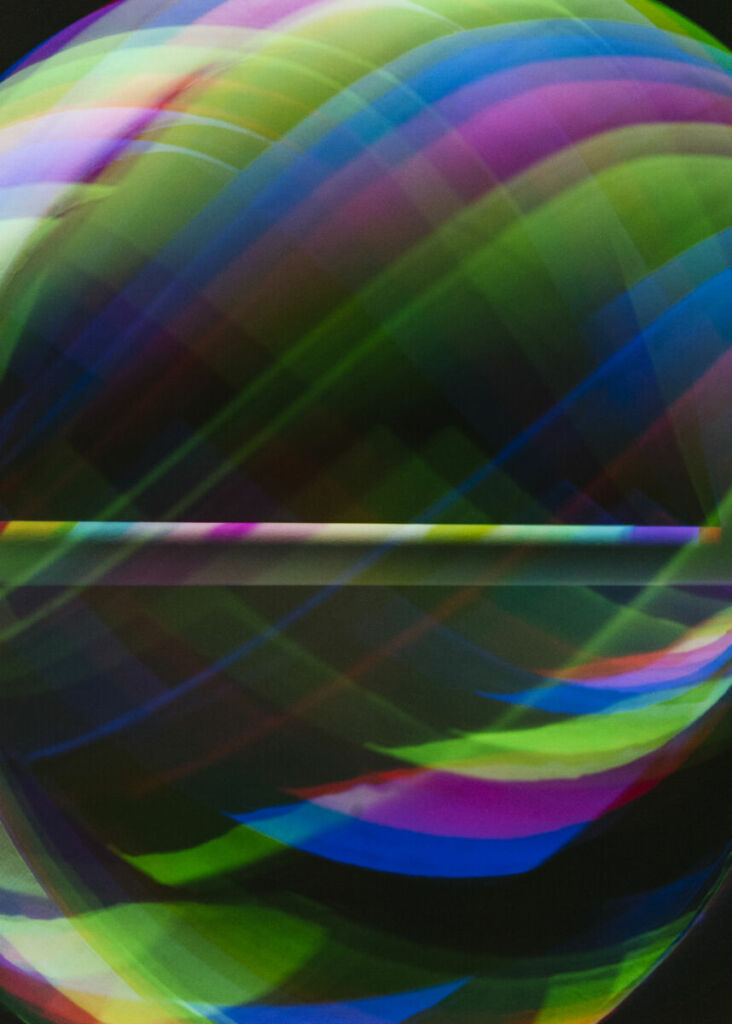

Through these experiences, I want the audience to experience a state of heightened perception and awareness. For example, in More Moiré, the installation gradually immerses the audience in a landscape of light, sound, and shifting moiré patterns. Initially, visitors might feel a sense of disorientation, but as they adjust, they begin to experience the installation in a deeper, more meditative state. The goal is for them to see and feel things that aren’t present in the physical installation but are triggered by it, such as hallucinations or an altered sense of space and depth. The significance of these experiences lies in their ability to provide a portal into different realities and states of mind. My works challenge the audience to engage with their perceptions and consciousness by manipulating primary phenomena of light, sound, and movement.

These experiences are not just about the sensory overload but also about finding those ‘sweet spots’ where certain combinations of stimuli fit perfectly, creating a sense of truth and coherence within the chaos.

Chasing The Dot is your first solo museum exhibition, on display at Rijksmuseum Twenthe from June 28 onwards. First of all, congratulations on this accomplishment! Tell us a bit about the exhibition and how it came about. What thread runs through the presented works?

Thank you! I feel blessed and honoured to have the opportunity to present my first overview exhibition covering seven big spaces in the museum. I’m presenting six rather big installations, and it’s the first time they’re presented alongside each other in a museum. The exhibition, called Chasing the Dot, has multiple threads— it moves from the physical, the matter, inwards towards the mental, the mind, from light towards total darkness.

Two brand new works have been developed specifically for this exhibition. Can you say a few words about them?

Chasing the Dot is a new work I’ve been working on for many months. It builds upon an earlier work and is essentially research into different patterns and dots, but in the past year, I have gone deep into this one. In the basement of my studio in The Hague, I created this little closed-off space where I spent many hours experimenting with light, colour and sound. To research colour, movement within other material makes focusing on the dots more direct or even necessary, if that makes sense.

Other than Chasing the Dot, I have long wished to make a more physical object. So now, for the first time, I’m making a non-kinetic sculpture. It still plays with the same phenomenon, the materialisation of hallucination; however, it’s a result of my colour studies. I’d love to create more work like this, sculptures that still clearly speak about colour and movement.

Next to these two works, which I’m excited about, is a new hypersculpure involving spinning fans that I’ve been building. It’s still a work in progress, but I would say it’s a double homage – to Olafur Elliasson’s fan, which was a direct homage to Marcel Duchamps’s fascination with movement. As my fans dance with each other in this choreography that might both grasp and confuse the audience, there’s also this connotation of crashing into each other, which confronts the viewer with the space, objects, and their sounds. It’s constantly pushing and pulling; this tension is a consistent thread throughout my work.

Your work is often described as immersive. Immersiveness has become part of a trendy phraseology used to market “experiences” rather than describe encounters with certain types of art. A big part of this is due to the role of social media and the attention economy. What is the function of social media vis á vis installation art, or the ramifications thereof?

That’s an interesting one to think about. On one end, it’s nice that this movement has opened up media art so much. Some social media accounts highlight art that some people would never have seen. And there’s so much great art out there. But also, some works automatically look very good on screen, while others don’t. Some of my work doesn’t come across on social media simply because a camera can not capture it. In general, experiencing any work is always a different experience, a multiplex experience, versus trying to experience it on your phone. Some works are not meant for phone speakers, headphones, or tiny screens. So, it changes the experience massively. For some work, that has fewer implications, or some might even consider some works being created with Instagram in mind, but for my work, it’s tough to explain or even capture on social media.

What is more important: knowing or not knowing what you’re doing?

Knowing that I’m never knowing? As I mentioned, my work is about experimental research and seeing where that leads. I never know upfront, and I learn as I go. It’s very process-driven, navigating between the two different states of knowing and not knowing. But if I really had to choose, I would go for not knowing, as there’s still so much to learn and explore.