Text by Natalie Mariko

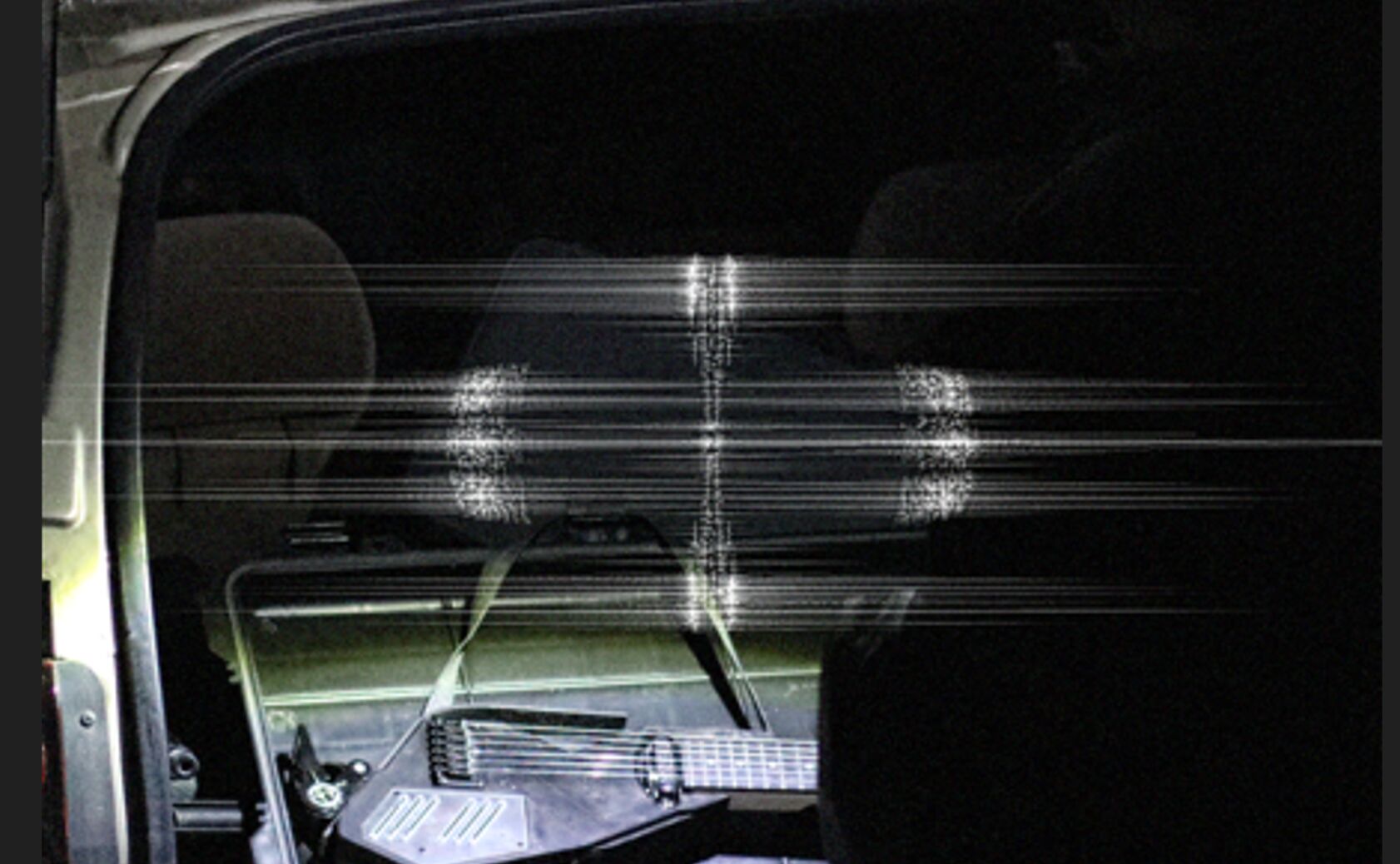

Lights down. Two figures carrying gun cases walk to the centre. A screen flashes nightmarish behind, landscapes morphing cataclysmic as sounds rush, slapping like the strike of a meteor. A sonic war plays out between sweet melodic sweeps and a crack which seems to have opened up in the sky above us. The figures punch at matte-black geometries—uncanny militaristic replicas of musical instruments. A voice warbles metallic through the din. A banshee joins. We won’t get through it this time.

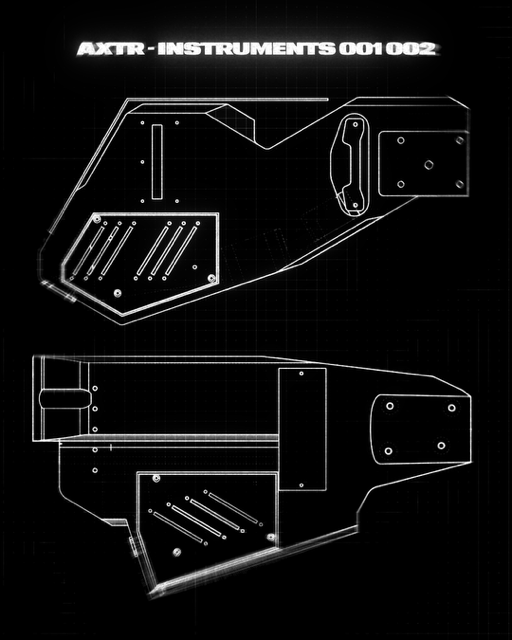

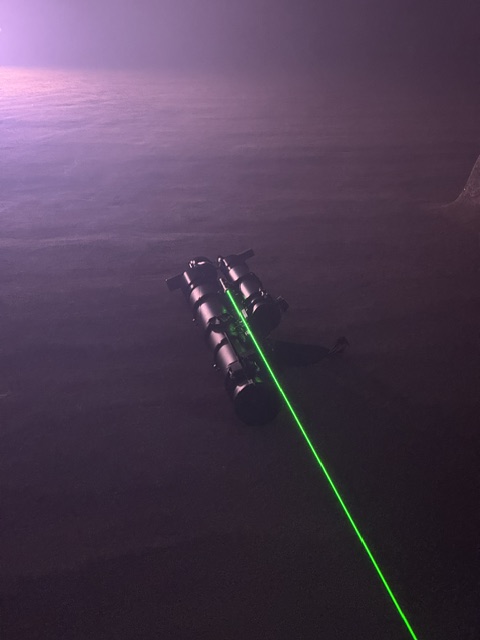

Axontorr is the collaborative audiovisual research project between visual artist Axonbody (Simon Kounovsky) and multi-hyphenate musical Wunderkind Oliver Torr. Their stage show is the culmination of several disparate artistic strands—as much experimental electronic music concert as carnivalesque Happening, complete with 3D-printed and self-designed instrumentation (traditional elements like a guitar, but also things like: a laser-mounted steel body zither; a flute with sliding pistons; a pitch-controlled air-raid siren; and a mortar-shaped resonating bass) and frenetic self-made visual projections. There’s a sense one’s caught in the centre of a supernova.

But if you talked to them outside of this space, you’d hardly expect it all came from them. The men are quick to laughter and talk animatedly, with boyish glints in their eyes, about how much fun they’re having. A 3D printer whirrs in the background and the wide marble-floored living room of Torr’s Athens apartment is populated by gadgets and electronics of every shape and description and so more closely resembles an engineering workshop than strict living space.

A screen mounted on the wall plays the eye of a CCTV camera pointed from the balcony out into the street, but the display is so broken that one can only see the phantom blinking of headlights and the almost shapeless bulges of bodies walking by and so even the décor has a functional research or artistic purpose. They heave giggling the huge weight of the printer and place it in the other room.

Their debut album, SETTINGS, was released on the 28th of November with a launch party at Fuchs2 in Prague, which included performances by Evita Manji, Abadir, Kodiki and more. Communal spirit and non-hierarchical collaboration are central to their project, Kounovsky tells me, falling cross-armed into the couch surrounded on all sides by books, synthesisers and physical research materials. We want to open-source what we come up with. We’ll have releases as a more traditional musical project, but we also wanted to release some body of work that would also contain the code and 3D objects and some sort of blueprint showing how to repeat, let’s say, the guitar or the bass we made.

Ideally, I see Axontorr as a research project, says Torr as Kounovsky leaves the room to check the printer, And if we can share what we come up with and have people share their ideas with us, we can all grow together. Real world, physical stuff – releases and so on – that’s all just a part of the process. A release just means the end of one research strand. So elementally crucial is the notion of communal involvement, they ask me to MC their launch.

Punk was the first thing, Torr explains, I started playing guitar when I was nine or some shit. And then I had a punk band when I was 12. He runs his hands through his hair. It’s a Typical childhood revolt story. Because my home was ‘broken’ in some sense, and that was the escape. There’s so much rage in playing three chords over and over and screaming and not necessarily needing to know the musical background of everything you’re doing, but engaging with it as a visceral or emotive form of expression.

I ask him what his first experience of punk was, and from the other room, Kounovsky offers: Jimi Hendrix burning his guitar at Monterey in ’67. Torr laughs, Hendrix in ’67.

Most interesting in their process is the intersection between digital and analogue outputs. AI generation is like Eno’s oblique strategies, visual information from dreams makes its way into the 3D instrument renderings. I don’t differentiate between the digital space and the physical space, Torr says as he walks into the other room where Kounovsky is kneeling next to the printer, The digital space is just an augmentation of me. Everything that I use, all the tools, are just augmentations of my thoughts and my mind.

What are you printing? I ask. A flute, Kounovsky says, toying with the printer settings. I was trying to think of a wind instrument to build, so it’s basically an augmented ocarina with a pressure sensor inside, Torr elaborates. You blow into it and the pressure sensor sends MIDI signals. You can control synthesisers with your breath.

The men smile and slap each other on the shoulders and walk me back into the living room.

It’s funny, Torr laughs; we both have really funny dreams. Yesterday, I dreamt Simon and I were in this sci-fi world, and we had laser harps, and we had to play specific tunings to advance in this world. And that’s how I got the idea of fixing a laser to the harp to have it control distortion. They lean into the couch and crack open beer cans, folding into the cushions. And Simon has sleep paralysis. Like sleep paralysis demons. And the weirdest thing is how I can see that in what he ends up actually creating. Our subconscious really controls our individual outputs. This interconnectedness of the subconscious is really spiritual, special. It’s cursed—in a fun way.

This sense of fun and free-associative discovery contrasts with the chaotic, violent immediacy of their music and live sets.

There is definitely this link with chaos in the sense that we try to integrate as many organic sources as possible in the process, Kounovsky explains, AI can be one in the sense that it’s based off of how the brain works.

We have a maximalist approach to creation, Torr adds, Maximalist in that there aren’t really boundaries in the idea generation process. For example, we tell the computer to ‘make a car that plays a chord when you drive’, something strange like this, and then from that derive the things that actually make sense. And then these strange ideas focus and amplify.

Kounovsky moves his hands like waves over one another and nods his head. The initial push was when I was probably 7 or 8. I saw this installation in the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. Paradise Omeros from Isaac Julien. It was a three-screen dream sequence about island ceremonies. It really transported me. Similar to what Oliver was saying about punk, the simplicity of playing, creating alternate realities, and just having something inside you that you need to channel somehow. He pulls his drink to his chin, you use and respond to whatever means make sense to you.

There’s a perhaps mistaken tendency to view analogue and digital as entirely discrete means of creativity, and many creators nostalgically long for a return to the former. The common phrase being, ‘AI is going to replace X’. It’s easy to pump out a 5,000-word article by putting a prompt into ChatGPT. But with Axontorr, the men seem to be physically repudiating the notion, taking disparate technologies that are supposed to be physically limiting or otherwise replacing creativity and integrating them into a totally new form of expressivity.

But it’s also exactly the same thing that everyone’s always been doing, Torr looks off into the distance, I think most people who are afraid of AI are people who are not using it. Whoever’s active in art, they know they can go further if they use AI to their advantage. The corners of his mouth turn down, and he shakes his head. It’s probably a generational thing. Like when people were afraid of electricity or phones or photography.

Kounovsky sits up and laughs, Dali said the phone kills romantic love because you can’t send letters anymore. That’s bullshit.

A horn rises up from the street below, and the screen mounted on the wall blinks light into the room. Torr looks up and points expressively in its direction; Peter Edwards from Casper Electronics said, ‘I want to sit on the rock and then lift it and see the bugs below.’ There’s a whole ecosystem and world going on beneath. That’s also what we want to do: flip the rocks and see what’s going on underneath, interact with it somehow and then point that outward at an audience to invite them into that form of play.

I think this approach of ‘just do it’ is really prominent for us. If I don’t know how to do X, well, the internet is right there. You have the hive mind. Your brain is not just the things that you think. And you don’t have to fucking go to school to learn stuff. This top-down model of education doesn’t particularly seem to make sense anymore. We’re all an apprentice of the internet in some way. You choose your vocation and now you have all of the tools available to everyone on the planet at the same time. To engage with and become a master. Everyone can do this. Both of them smile, look to one another and then to me, Everyone do it.

Kounovsky holds his head in his hand and leans further into the couch, I did a year of cinema school and dropped out. Most of the 3D and stuff is just learning from the internet. Basically, pretending I know how to do something if I get asked to do it and then googling how to do it and solving problems. Not just acting with curiosity…

Obsession, Torr interjects. Survival.

Exactly. We couldn’t live without it.

Or laptops.

Or each other.