Interview by Daniela Silva

In an era where digital interfaces are increasingly streamlined for speed and efficiency, Korean artist and web designer Yehwan Song invites us to reconsider our relationship with the internet. Her work challenges the conventions of user-centered design by embracing discomfort and unpredictability, urging users to engage more deeply with digital spaces.

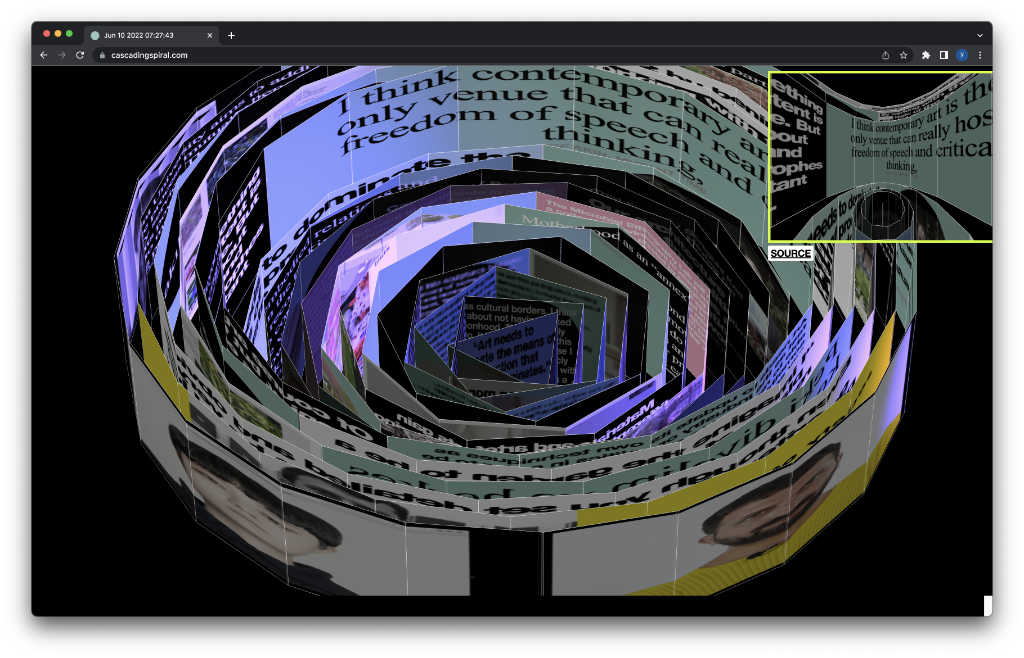

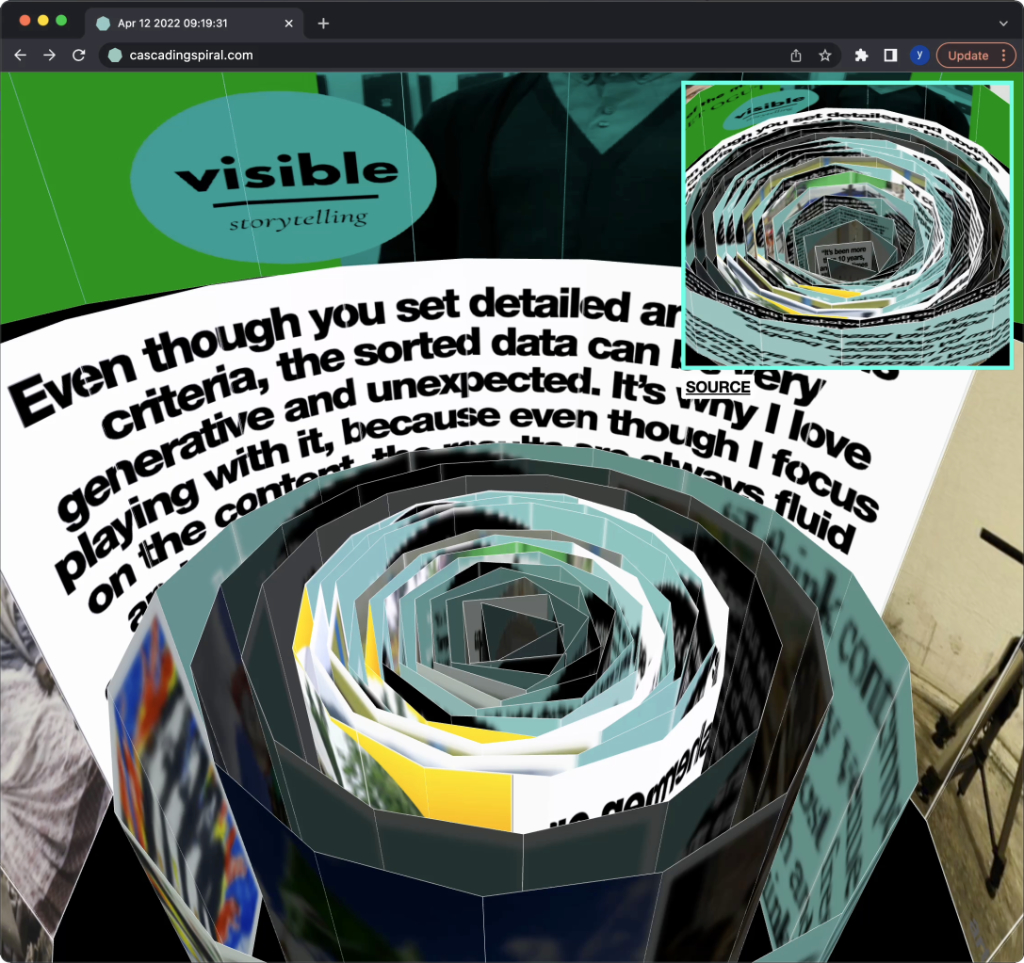

Yehwan’s background in visual communication design laid the foundation for her critical approach to web design. Her time at the School for Poetic Computation further influenced her perspective, exposing her to a community that values critical thinking about technology and its societal impacts. This environment encouraged her to question why user interfaces prioritise ease and efficiency over diversity and expressiveness. Her project, Cascading Spiral, exemplifies this philosophy. Inspired by spider webs and meteorological charts, the dynamic, radial web interface archives and live-captures artists’ works, creating a circular, interconnected shape that evolves. This approach reflects her belief that form should follow content, allowing the structure to grow organically as new layers are added.

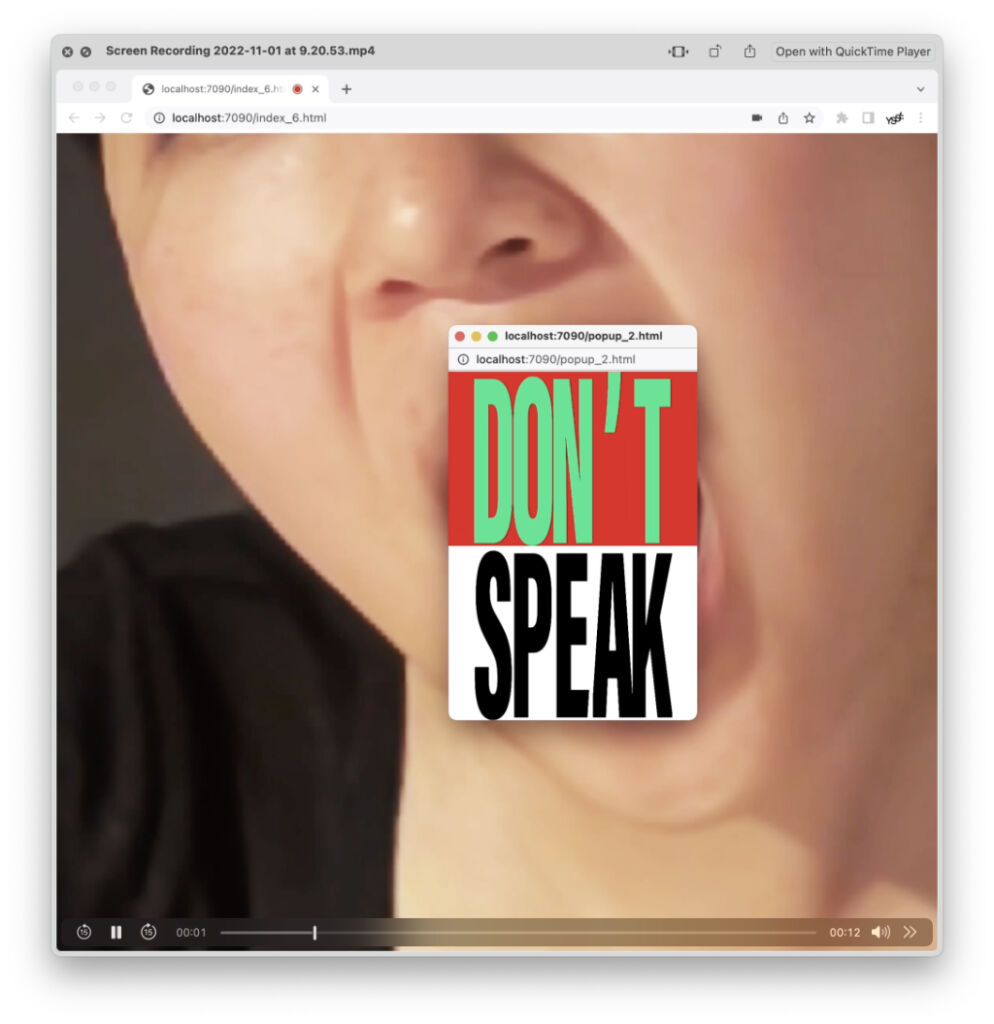

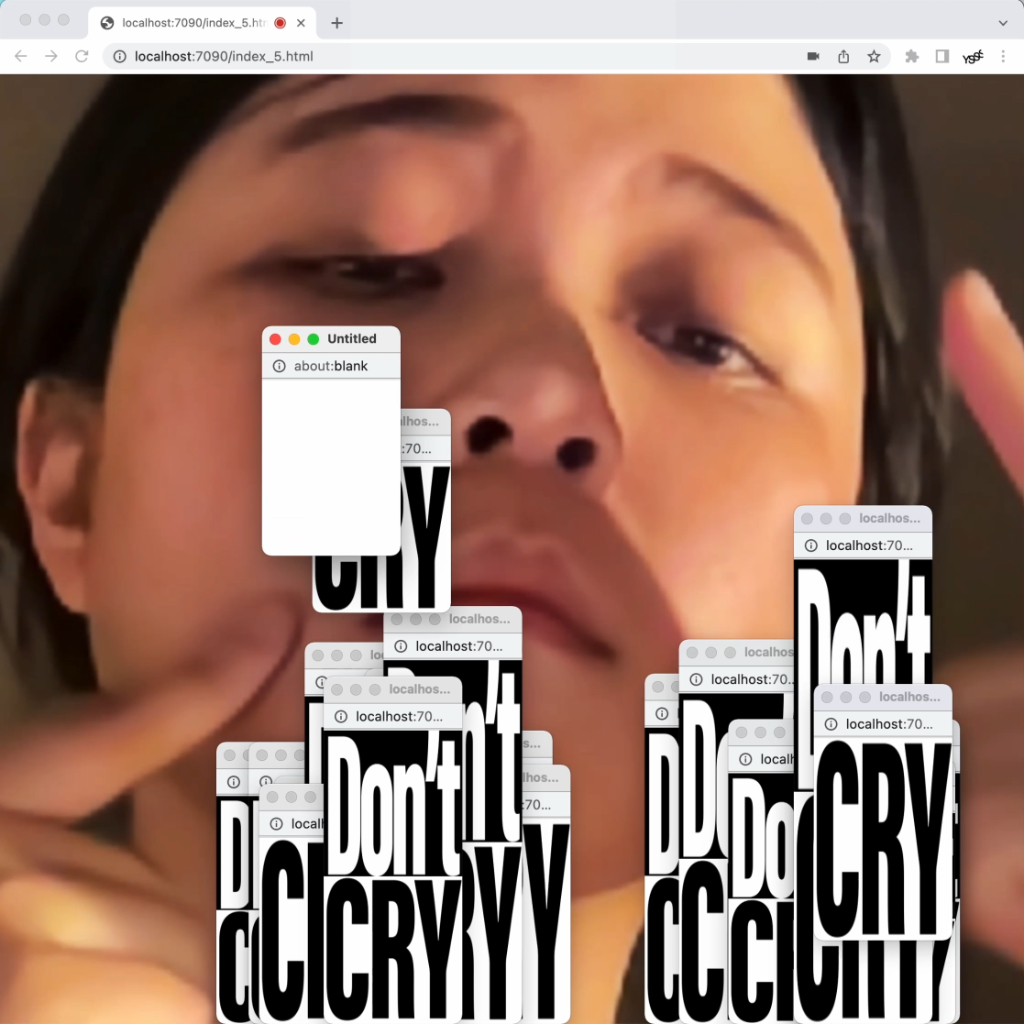

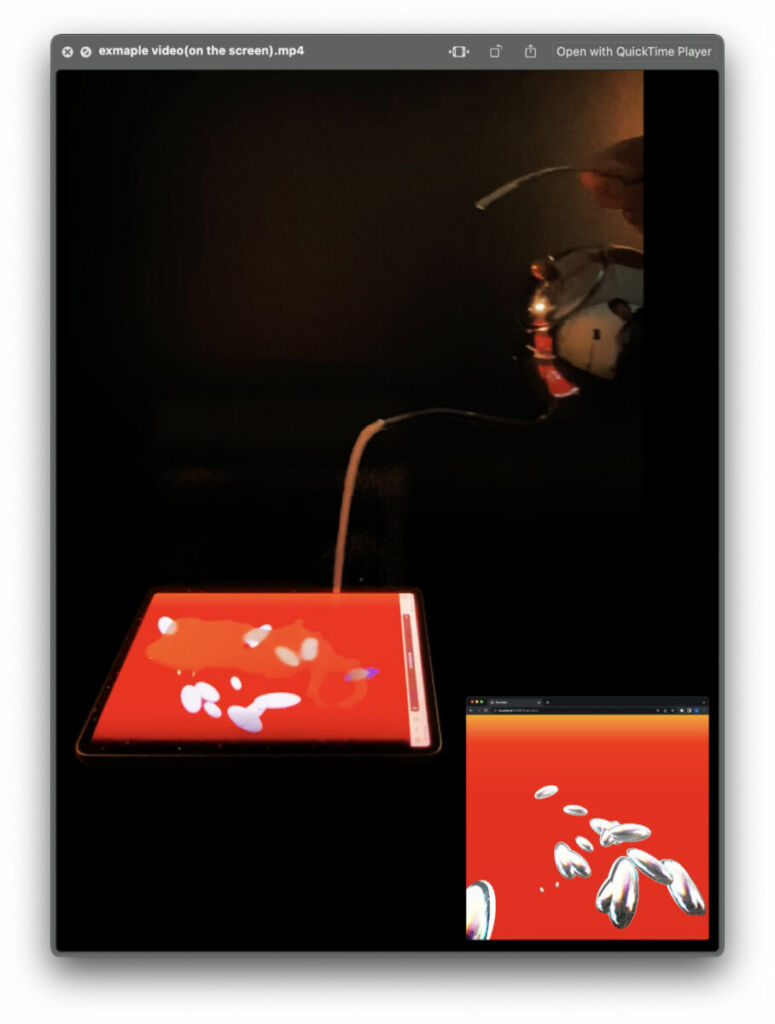

In Newly Formed, a collaboration with the Helsinki Biennial, Yehwan integrates machine learning to reframe digital accessibility. By bringing the museum’s collection archive online interactively and engagingly, she addresses inequalities in digital environments and explores the intersection of technology and public art. Yehwan’s Aquarium transforms a flat web interface into a three-dimensional, tactile experience, bridging the digital and physical realms. By simulating the act of dipping a finger into a real fish tank, she challenges the notion that online and offline worlds are separate, suggesting that we live in both simultaneously. Her piece, Cracked Eggs, uses unconventional inputs, such as raw eggs, to generate digital art, highlighting the relationship between chaos, control, and creativity. By playing with the assumption that touchscreens only respond to human touch, she encourages users to reconsider how technology shapes our understanding of the world. And in Today I Walked, Yehwan simulates the act of walking through finger movements on a keyboard, offering a poetic gesture on the internet. Created during the pandemic, this piece suggests that immersive visuals aren’t the only—or even the best—way to create meaningful online experiences.

Looking ahead, Yehwan is interested in exploring linguistic and cultural barriers on the internet, examining how online experiences vary depending on one’s location and nationality. This inquiry began with her project Whose World How Wide Web, and she anticipates delving deeper into these themes in future work. Through her innovative projects, Yehwan Song challenges us to rethink our interactions with digital spaces, advocating for a more expressive, inclusive, and experimental web.

Your work challenges the conventions of user-centered design by embracing discomfort and unpredictability. Could you share how your background in visual communication and your time at the School for Poetic Computation have influenced this approach?

I studied visual communication design in school, and I began to question why UI/UX is so focused on speed, ease, and efficiency compared to other media, such as posters or books. That question became more pronounced as I worked in the UX/UI field—how design turns into strategy, and humans become users. The School for Poetic Computation was a great place to start exploring this idea. It was full of students with critical perspectives on technology and big tech companies, and it assured me that thinking critically about UX/UI is important.

You’ve described the internet as a space that often prioritises efficiency over diversity. How do you envision a more expressive and inclusive web, and what role does your concept of “anti-user-friendly” design play in this vision?

I hope that “anti-user-friendly” design can remind people of the web’s diversity and its potential to be expressive and experimental. The web doesn’t always need to prioritise efficiency. Not every website needs to be expressive either, but we need to leave room for diversity—and for those spaces to be accepted.

In your project, Cascading Spiral, you created a dynamic, radial web interface inspired by spider webs and meteorological charts. What narrative or experiential goals did you aim to achieve with this structure, and how did users interact with it over time?

The concept was to archive and live-capture all the artists’ works during the biennial. Every time I added new content, it created a new layer—like tree rings—eventually forming a circular, interconnected shape full of content. I wanted to reflect the idea that form follows content. The growing layers over time revealed how the project aged—much like a tree accumulating rings.

Newly Formed, your collaboration with the Helsinki Biennial integrates machine learning to reframe digital accessibility. How did this project address inequalities in digital environments, and what insights did you gain about the intersection of technology and public art?

The goal was to bring the museum’s collection archive online and create an AI-based, more interactive, and engaging website. The goal was to make the collection more accessible and raise awareness of these large archives by presenting them in a more inviting way.

Your piece, Aquarium, transforms a flat web interface into a three-dimensional, tactile experience. What inspired you to bridge the digital and physical realms in this way, and how do you see such interactions reshaping our understanding of web spaces?

I was thinking about how the online and offline worlds are not entirely separate—we live in both simultaneously. I wanted to explore how the web could exist in 3D space, rather than relying solely on flat screens. That’s still something I’m working on.

In Cracked Eggs, you use unconventional inputs—like raw eggs—to generate digital art. What does this say about the relationship between chaos, control, and creativity in your work?

I was intrigued by the fact that touchscreens respond to most liquids and conductive materials, yet we assume they only work with human touch because of how they’re framed. I wanted to play with that assumption—how the term “touchscreen” and its visualisation shape how we understand the world. I believe that some chaos is often necessary to break control, and as that chaos becomes accepted, it evolves into a form of creativity.

Your project, Today I Walked, simulates the act of walking through finger movements on a keyboard. How does this piece explore the embodiment of digital experiences, especially in the context of isolation during the pandemic?

I wanted to create a poetic gesture on the internet. At the time, everyone was rushing to build metaspaces online. I wanted to suggest that immersive visuals aren’t the only—or even the best—way to create meaningful online experiences.

Looking ahead, what directions or themes are you eager to explore in your future projects? Are there particular technologies or concepts you’re interested in integrating into your practice?

I’m interested in the linguistic and cultural barriers on the internet, as well as how the online experience can vary depending on one’s location and nationality. This started with the project Whose World How Wide Web, and I’m looking forward to exploring it further.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Lack of time.

You couldn’t live without…

M&Ms….