Words by Lula Criado

Heather Barnett is a London-based visual artist and researcher working with living systems and scientific processes turning slime mould into stunning art. By blending art with cellular differentiation and organism intelligence she blurs the boundaries of art and scientific research.

I met Heather in January when I attended the workshop focused on Physarum polycephalum, she was running The Society of Biology in London. Her talk introduced diverse areas of research and her workshop offered an intimate experience with the materials Heather works with. All the participants designed a pet slime mould, allowing a deeper understanding of how the slime mould behaves.

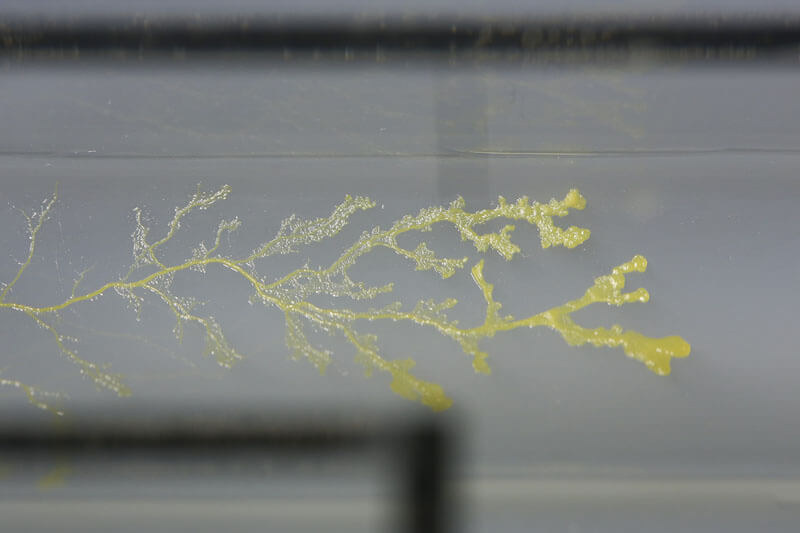

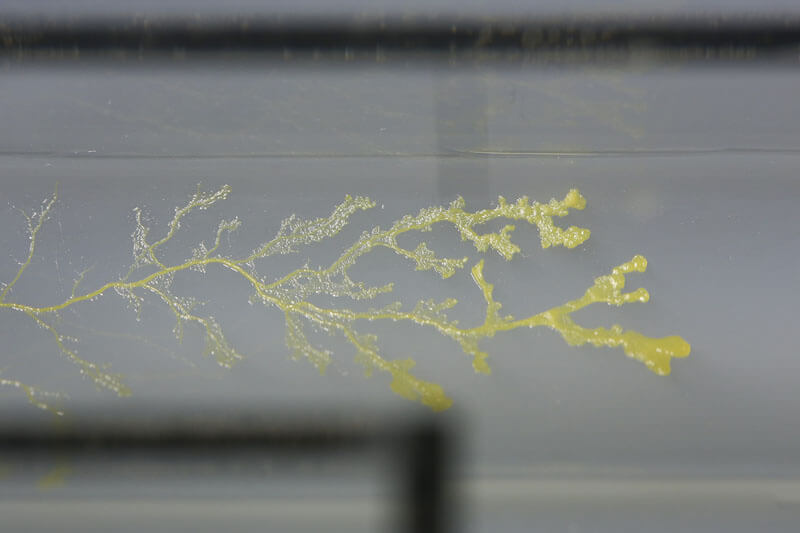

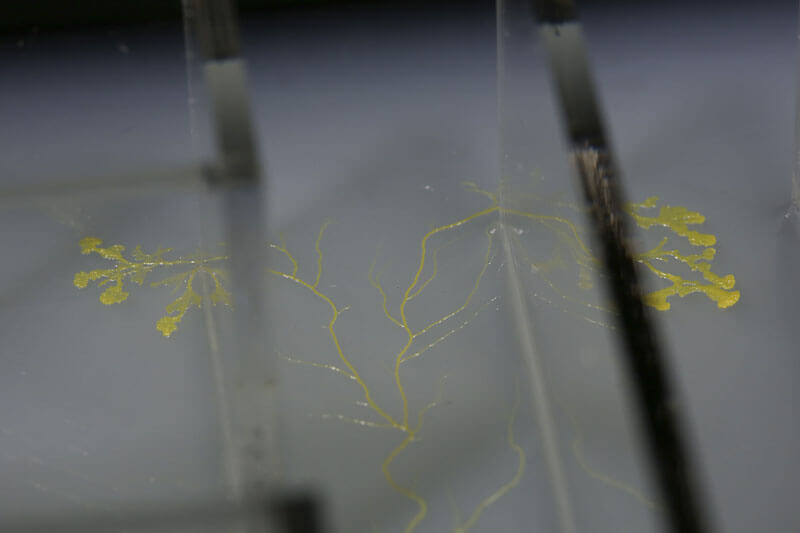

Fascinated with living biological systems and Physarum Polycephalum, Heather Barnett has developed her project The Physarum Experiments: Slime mould drawings and animations. Physarum Polycephalum is the “slime mould” that Heather’s work centres around is an organism considered to possess a very primitive form of intelligence and used as a model for studies focused on cell motility.

Taking inspiration from scientific research and cellular computation, Heather explores the behaviour of the Physarum polycephalum and captures its motility patterns and movements. She is also working closely with a musician to compose music in response to these motility patterns.

Heather Barnett has always been interested in “what lies under the skin” and she remarked that because of this her “initial engagement as an artist with biological systems was with medical processes”. Heather has translated her creative collaboration with science into a project called Cellular Wallpaper which is a collection of wallpapers inspired by the hidden microscopic world.

You are a visual artist, when and how did the fascination with biological systems come about?

As a child, I enjoyed watching operations on television. I can remember being fascinated by the mess and complexity of the human body and amazed at how it all worked.

I have always been interested in what lies under the skin, so my initial engagement as an artist with biological systems was with medical processes, mostly at a cellular level, but I was also interested in the processes of medicalization (testing, laboratory protocols, diagnosis, etc).

My first residency was in a hospital, exploring notions of medical identity, i.e. what happens to a patient as they enter a medical environment. I talked to patients on the ward and followed their samples to the laboratory, where they were no longer present as a whole person, but as a sample in a test tube.

After this, I started working with skin organisms, fascinated by the number of microorganisms we harbour that are harmless until amplified by microbiological processes – where they are exaggerated and become potentially harmful to their host.

This started my interest in working with living biological material, where I can predict certain behaviours and responses but ultimately cannot control the outcome. I have worked with complex organisms (cuttlefish and fruit flies), the botanical material (seeds and plants), and microorganisms (bacteria and slime moulds).

I think it is good for an artist to have to negotiate with their material, to not be in complete control of the media. I see this work as collaborative, to a point.

Why Physarum polycephalum instead of another microorganism?

Physarum polycepahalum is interesting on many levels, as a subject of study and as a material to work with. As a biological organism it has a pretty amazing life cycle. It is used as a model organism in so many areas of research, including cellular motility, network efficiency, and biological computing.

I also find it beautiful – the dendritic patterns it forms when searching for food are reminiscent of branching forms we see at many scales within nature (e.g. river deltas, leaf venation, tree branching, lightning strikes) and within our own bodies (veins, blood vessels, neural networks).

This single-cell organism is attributed with a primitive form of intelligence, problem-solving skills and the ability to anticipate events – not bad for an organism that has no brain, no organs, and no central nervous system.

Its intelligence lies in the rhythmic flow of protoplasm and the detection of chemical signals. It is also a highly cooperative organism, with individual cells coming together to maximize efficiency in order to survive. As a species, we can take many lessons from observing it!

Physarum polycephalum is a slime mould that eats fungal spores and bacteria, how do you feed your creativity?

I eat fungal spores and bacteria!

You run an experiment to see if humans can follow a few simple behavioural rules of plasmodial slime mould in order to communicate, navigate and cooperate. What happened? They did do it? Any interesting conclusion about human behaviour?

The ‘Human Slime Mould Experiment’ was the third part of the Being Slime Mould trilogy, exhibited as part of the BioDesign exhibition at the new museum in Rotterdam. Devised in collaboration with Daniel Grushkin (co-founder of GenSpace, New York) the ‘enactment’ was a playful way of testing human navigation and cooperation abilities, as compared to the slime mould.

Tied together (as a single-cell organism) and following slime mould rules (i.e. communicating through oscillations, operating as a single entity, responding to their environment) a group of strangers had to navigate in search of food, reshaping and reconnecting when obstacles were met, forming networks between food sources.

We ran the experiment on the opening night of the exhibition and the following day in the park, with some interesting observations. It was incredibly difficult for people to let go of their complex human behaviours, but people earnestly attempted to operate by simple low-level rules and engaged with what we were doing on different levels.

Whilst in many respects it was a ludicrous experiment, one of the most interesting things to emerge was the spontaneous discussion afterwards, people commenting on the power of being bound to strangers and given problems to solve.

The individuals who took part bought their own interpretations and observations, a psychologist observed the individual and group dynamics of the super-cell, a biologist compared the behaviour to bacterial communication, and an urban designer thought we were encouraging greater autonomy and agency in how city spaces are ‘owned’ by the community.

I don’t think we drew any conclusions, we weren’t trying to prove anything, but use the idea of an experiment as a means of engaging people with ideas of collective cooperation and primitive intelligence. And on that level, it was really successful and provided a stimulus for some really interesting conversations with a bunch of strangers.

If you could visit any scientist’s mind, who would it be and why?

Tricky question, I’d like to get inside the heads of many creative, insightful people (including scientists). Darwin is an immediate choice, because of the enormity of his discoveries and the implications they had for him publically (in publishing theories which contradicted dominant ideologies), and personally (with regards to his religious beliefs and the impact of his discoveries on his relationships).

Galileo would be another choice for similar reasons, so I guess I’m attracted to the troubled minds of those whose thinking went beyond what was acceptable or conceivable in their time. A few moments spent in Einstein’s head would be pretty incredible too.

What keeps you up at night?

I’d like to say ‘thinking beyond what is acceptable or conceivable’, but in truth any sleepless nights are caused by mental lists of things I should have done or need to do, dotted with the odd moment of inspiration. I keep a notebook by my bed for all nocturnal meanderings.

You couldn’t live without…

I’ll take a Darwinian position on that one and say that in order to survive we need to respond and adapt to our environment, so by that principle, we should be able to live without anything – except, of course, oxygen and other fundamental requirements for life.

One for the road… I find your project micro-design really inspiring and innovative, how did you come up with this idea?

Micro-designs is an interior design collection inspired by biological patterns, particularly at a microscopic level. The project developed from a body of work I did working with the pathology team at Poole Hospital in Dorset, UK, whilst I was an artist in residence in 2000. I developed a series of Cellular Wallpapers, chintzy decorative patterns derived from microscopy images of human cells, my own cells.

On one hand, it was intended as a purposeful tongue in cheek take on ‘interior design’ – the ultimate narcissistic statement in interior décor – but there was also a serious attempt to engage with medical imagery in a hospital environment in a subtle and sensitive way. Hospital art is often intended as a distraction, to take the patient’s mind off their situation. But what if it could be used as a means of breaking down barriers to medical information or of breaking taboos? We can be incredibly squeamish about our insides, and biology is thought of as very messy – but there is complex and beautiful design inherent within biological systems.