Words by Meritxell Rosell

Loren Kronemyer, an artist from Los Angeles based in Perth, focuses her work as a means to bridge the language gap between humans and other life forms, challenging her role and involvement as an artist in the process. Communication, the act of drawing (one the most basic forms of both artistic expression and communication) and the ephemera are central to her work.

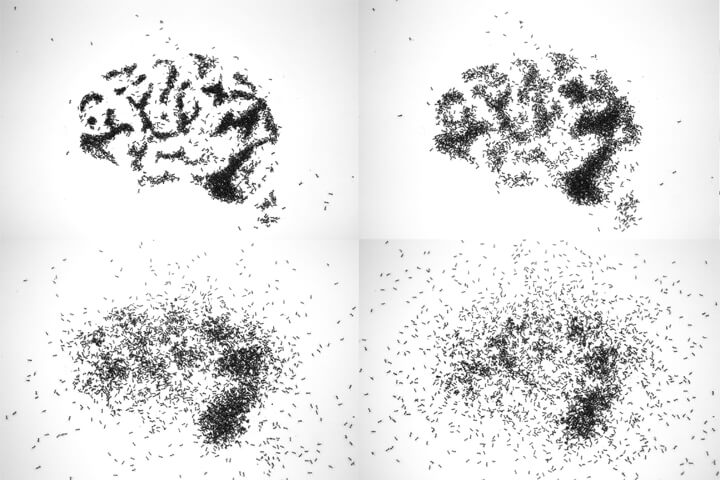

Myriads, her Symbiotica MA graduation project, is an exploration of insect communication within a human control frame. Communication is expressed here as a form of living drawings executed by this form of super-organism intelligence, ants. Images and words are formed but only briefly, hints of the short life span of the artist´s control over the system. In Worm Wide Web, she takes back the ideas consolidated in Myriads and brings them to the next level; worms, beetles and other more complex organisms praising this innovative communication and ultra-human intelligence strategies.

The central issues of Loren’s work come out together in a very poetic and posthumanistic way; evocative of these very human anxieties, our interaction with the environment and the other species we co-exist with, and the physical and cognitive boundaries between them.

Myriad Brain Gif (2012)

You are an artist working at the intersection of art and science, when and how did the fascination with biological systems and living materials come about?

For me, it came about very organically. At a certain point, I stopped being interested in just representing living systems and wanted to work with the systems themselves. I’ve always jumped around a lot between media, my work is driven less by the formal properties of any one tool than by the themes and concepts I am communicating. At a certain point, it made sense to make the phenomena itself the media rather than to represent it.

With that decision there comes a host of challenges and opportunities since living material is sensitized and responsive and alive, but all of those become part of the process. I get excited by living things and I love working with them.

What are your aims as a bioartist working in between science and art?

Although I work with living material, I don’t identify myself as a bioartist, and I don’t recognise the difference between science and art anymore. I am not preoccupied with cataloguing their crossovers or explaining their shared history or revelling in the novelty of bridging the two. To me, the differences between the practice of art and the practice of science are so small, that discussing them isn’t productive anymore.

Scientific journal articles read like conceptual performance instructional works to me. Discoveries made in the course of artistic research shape my understanding of the material world. The aim of my practice is to use all of the tools in my toolbox to engage with human culture and create documents about our absurd positioning as a species in this world. It’s a lofty goal, but I am slowly and incrementally responding to it, and it feels like the right way to spend my time. I draw, but the lines I make are articulated and erased through the movements of insects, cells, and my own organs or body.

Promoting ephemerality is one of my main concerns, and I am always working towards an artistic practice that is transparent regarding its physical impact on the world.

Is art helping understand scientific issues and science or it is challenging what society understands about them?

I don’t think of that as an either/or proposition. Understanding something comes from having your assumptions of it challenging. Art is a good tool for communicating issues. Things like ethics, responsibility, fear, loss, and hope – these are things that art can help us understand well and on a visceral level.

Of course, art does not have to be didactic or promote understanding. It can be superficial as well, and in this respect, art is used to communicate the beauty and rarity of certain disciplines without going in on an ethical level.

To me, the appeal of working as an artist is that I have social permission to blend disciplines, to be opportunistic with what tools I use, and to use the power of my work to communicate however I decide to.

These are privileges that I treasure immensely, so I try to keep an open framework when discussing what art does and doesn’t do. Yes, there is the potential for art to communicate science to a broader public, and yes, art had the power to challenge the understanding of science. Is science helping people understand artistic issues?

Solitude or loneliness, how do you spend your time alone?

I love taking time alone, although I work collaboratively very often. I wonder if the work I create when I am alone is very different, usually very methodical and rhythmic and slow and weird. When working in a social context, I prefer punchy, concise, and clever outcomes.

Of course, working with living material, one is never alone, but I like to think I can explore a bit more of a dream world when I am alone and not surrounded by the grounding practicalities of social contact.

I spend time alone working, drawing, reading, looking around, exploring the internet, pursuing short-term physical enjoyment, and generally letting my imagination run wild.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Self-consciousness and hunger.

You couldn’t live without…

Freedom.