Words by Meritxell Rosell

In this new era of digital data explosion, the availability to manage and store huge amounts of information has become a vital issue. This is particularly relevant to modern biology and bioinformatics, for which large amounts of very complex data are generated. DNA has recently become a focus of interest due to the high density of information that can encode: 4 coding letters to just the 0/1 in the binary system.

UK-based artist Charlotte Jarvis, who was captivated by genetics and biotechnology while doing an interactive design MA at the Royal College of Arts, has been closely working with scientists, molecular biologists more precisely, for the last five years.

In Blighted by Kenning by combining synthetic biology and biotechnology with concepts of language and communication Jarvis encoded the Universal Declaration Of Human Rights into synthetic DNA.

On the other hand, Dr Nick Goldman, a researcher at the European Bioinformatics Institute (Cambridge, UK) that had been developing a new technology to encode digital data into DNA [1], came across Charlotte’s work and they engaged in fruitful collaboration that led to Music of the Spheres.

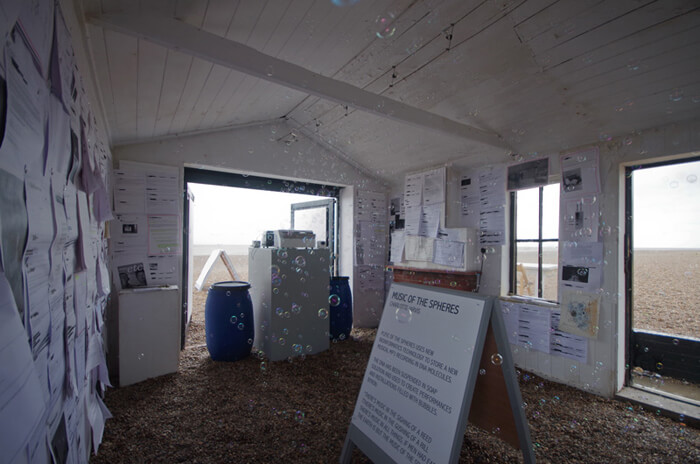

Music of the Spheres is an intricate and elaborated piece of art. With a name that evokes ancient Greece and the mathematical relationships found in nature is, the playful way in which it is delivered to the audience, what makes it deeply delicate and ephemeral but, one that can be perpetuated as persistence of common memory.

Music of the Spheres, which was presented at Ars Electronica in 2013, consists in encoding part of a musical composition into a DNA sequence synthetically synthesised. That DNA was then suspended into soap bubbles which were used to, literally, bathe the crowd at the exhibition sites. The complete piece cannot be listened to unless DNA collected from the bubbles is sequenced.

In other projects, like Ergo Sum and the ongoing Et In Arcadia Ego, Charlotte Jarvis uses her own cells along with molecular biology and cell culture techniques to challenge ideas of identity, self perception and even immortality.

Charlotte’s work, which exists in a varied number of forms: installation, performance, objects, photography and films, reveals her multidisciplinary interests and an extremely curious and restless mind. It is also her engaging discourse to demystify misconceptions about biotechnology and genetics that makes it even more appealing.

You are an artist working at the intersection of art and genetics. When and how did the fascination with genetics come about?

I became interested in collaborating with scientists during my MA. I did a course called Design Interactions at the Royal College of Art. It was a really cross-disciplinary program with scientists, designers and artists all thrown in together and encouraged to examine what the future might have in store. I had always been interested in science but up to that point I had not found a way to incorporate it into my art practice in a satisfying way.

I’m interested in working with genetics and biotech specifically because they are changing the world. Genetic technology is changing our perceptions of ourselves, of our bodies and of our environment.

Increasingly these technologies are opening up and becoming more accessible to people outside the scientific community – or at the very least scientists themselves seem to be increasingly interested in opening up their own practice and communicating what they are doing to a wider audience. These technologies fill me with wonder, I want to participate in them, shout about them, mutate them and question them.

What are your aims as an artist and researcher working in between art and genetics?

I’m interested in doing it. Literally doing. Many people who work in the sci/art scene don’t do this – instead, they hypothesise and create interesting scenarios inspired by science – “what ifs”.

“What ifs” can be magical but I want to do – and now that is becoming easier as this technology becomes more accessible to people like myself.

DNA sequencing technology is a great example of something that was once highly exclusive and become increasingly prevalent – and this is partly what attracted me to making this project. This is something we are all going to be interacting with in the near future. In the exhibition we have a prototype minION – this is a domestic device that can sequence DNA plugged into your laptop – it’s about the size of a packet of chewing gum.

Over the last few years, I have also been thinking a lot about science as a medium. At the moment artists/designers/performers/people writing about them etc often treat it as a subject. It is the subject of the work – i.e. this is a piece about stem cell technology/data storage / genetic engineering etc.

HOWEVER what I think is happening now – what I am trying to push my practice towards – is science as the medium to say other things. I suppose in art historical terms this might be “post-modern” – kind of.

To take the analogy to paint… Modernist paintings are about paint and the two-dimensional surface of the canvass – after the Abstract Expressionists, however, artists (go back?!) to using the medium to say something else – the medium is no longer the subject – it is just a means by which we describe the subject. I think contemporary artists are moving towards a place where we use science to describe and evoke other things.

What was the most difficult part of Music of the Spheres’ development?

As with most projects of this nature, the greatest challenge is sourcing the funding to make it. It’s not the kind of work you can sell after it’s made – it’s essentially performative – so you need to find a budget before the fact.

We had quite a rollercoaster with funding for this project, which is why it eventually took us three years to realise and in the end, we made it with a combination of sponsorship, a Kickstarter campaign and in-kind support. There was a real drive from the whole team to get the project made come what may and that really carried us through.

What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

My next project is called Et In Arcadia Ego. I’m collaborating with Prof. Hans Clevers and Dr Jarno Drost at the Hubrecht Institute to grow my own tumour. T

he tumour will be gut cancer that is genetically ‘Me’ – grown from my own cells in the lab. The tumour will eventually live in a specially designed incubator suitable for gallery spaces. I will make a durational performance with the tumour; sit with it in the gallery; watch it, feed it, care for it and confront it.

The project aims to examine mortality and create a dialogue with and about cancer.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Distraction.

You couldn’t live without…

My incredibly supportive partner James.