Words by Cathrine Disney

In opposition to the narrow role of consumer-driven design in the development of existing and emerging technologies, design duo Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby use design as a tool to critique, discuss, debate and speculate.

After 10 awe-inspiring years as Professor, Head of Programme and Reader on the renowned Design Interactions programme at the RCA, Dunne and Raby retired from their positions in 2015, leaving behind them a legacy of internationally recognised designers.

Currently, Dunne and Raby hold the positions of Professors of Design and Emerging Technology and Fellows of the Graduate Institute for Design Ethnography and Social Thought at The New School in New York, where they continue to stimulate the minds of designers, industry and the public, investigating the social, cultural and ethical implications of technology by exploring parallel worlds and fictional futures in what Dunne and Raby refer to as ‘designed realities’.

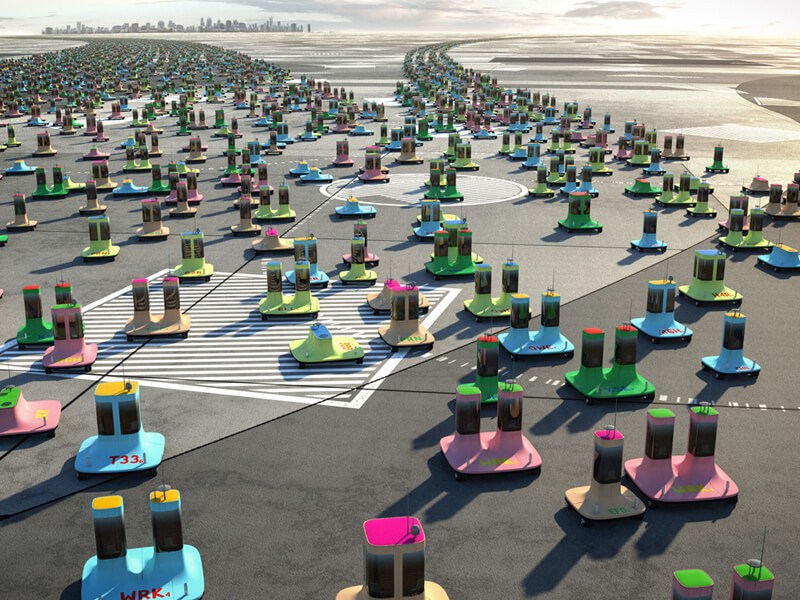

Dunne and Raby’s Between Reality and the Impossible considers an alternative world where the role of design exists to question, entertain and probe rather than to develop technology products and services that are sexy and more consumable.

The project consists of a number of scenarios, each suggesting an incompatible view to that of the Western world as the contented consumers and users we are ‘supposed’ to be. One of the themes explored in this project is in response to the looming overpopulation crisis and food shortages. The UN has predicted that we will need to produce 70% more food in the next 40 years to feed the world’s growing population [1].

Foragers suggest an interesting solution to these problems by bringing to light the potential of synthetic biology to enable us to develop new digestive devices inspired by herbivores that will allow humans to maximise the nutritional value of their urban environments.

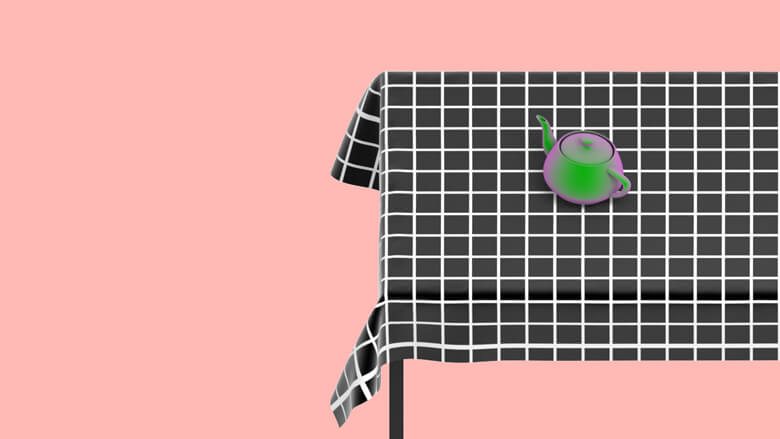

Their latest project, Meinong’s Jungle (Theory of Objects), attempts to communicate and utilise the theory of Austrian Philosopher Alexius Meinong that all non-existent objects and even impossible objects, such as round squares, should be included in any proper taxonomy of objects.

If it is possible to think of such an object, even though that object does not exist, it must have some sort of being. Fascinated by this concept, Dunne and Raby propose that this theory holds exciting potential to initiate new aesthetic possibilities for future thought-provoking works.

Your work is in the intersection of design, science and art; when and how did the fascination with them come about?

Since we were students, we’ve always been interested in the unique challenges technology creates for design and its impact on society. After we graduated, Fiona and I spent a few years in Japan, which had a huge effect on us; Tokyo was like a live laboratory for experiments in living with technology; it was a wonderful time to be there.

Until the late 90s, we focussed on digital technology, then around 2000, we became interested in the ethical issues surrounding biotech and wondered how we could get involved as designers. We set up a project with our students in CRD and DP at the RCA and began doing our own projects, which eventually led to the Design Interactions department.

At the moment, our focus is shifting from technology to ideology.

Your work is focused on the social, cultural and ethical implications of technologies. Is [speculative] design helping understand the role of technology in society, or is it challenging what society understands about it?

My experience working in industry after college exposed me to quite a narrow role for design in the development of new technology focussed on making tech products and services easy to use, sexy and more consumable.

A lot of our work since then has been about exploring other ways designers can get involved with technology, especially questioning assumptions driving its development and the opportunities and limitations it creates for everyday life, in the Western world at least, through a mix of critique and speculation.

We’ve recently become very interested in the formation of the world views that drive technological development. There’s a lot of knowledge available on developing new technologies, but how do you go about developing or constructing alternative worldviews?

This is something we’re beginning to explore in dialogue with people working in other disciplines like political science and anthropology. We’re currently gathering examples and investigating ideas that explore the conception, construction, materialisation and presentation of alternative realities, parallel worlds and fictional futures under the umbrella of ‘designed realities’.

What are your aims as [speculative] designers?

Our aim is simply to produce thought-provoking designs that, on one level, get people thinking about the assumptions behind the products and services they interact with in their daily lives and, on the other, explore what our technological world might look like if different values were driving its development.

Although we still believe in the value of speculating and critiquing through design, we’re not keen on the labels ‘critical design’ and ‘speculative design’ as they can be very limiting. It’s the acts of speculating, critiquing, problem-solving and so on rather than labels that are important for us. Although admittedly, labels are useful for discussing and debating an idea in its early stages.

If you could visit a designer’s mind, who would it be and why?

It would have to be Ettore Sottsass. A part from the breadth of his activities included directing Olivetti’s industrial design studio, generating new design movements and ideologies, and creating highly lyrical and poetic personal projects.

All his designs embodied a profoundly complex view of what it means to be human, one that is in stark contrast with the highly reductive view of the human as a consumer or user many of today’s technologies are designed around.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Creativity is not the issue; it’s a lack of imaginative thinking that concerns us. It’s very difficult to go out on a limb and propose a really new way of thinking about something or reimagining how we might live; there is so much pressure to conform, which is making radical thought very difficult, at least in design.

Being educators, we’re always exploring ways of setting up conditions for free imagining, a place where extreme creative risk-taking is normal. We’d like to see this happen more outside of design education as well.

The biggest enemy is the idea of the ‘real’ is limited to only what is possible now and the very narrow view of life and what design can do that goes with it.

You couldn’t live without…

Vast, bleak landscapes free from design!