Interview by CLOT Magazine

The Future Starts Here, the new major exhibition coming to the V&A Museum (London) this spring, 2018, explores technologies and designs currently being developed in studios and laboratories. It brings together for the general public more than 100 objects and products that have been underground for a while and the work of artists and designers who have been pioneering speculative scenarios.

The exhibition, produced by the Design, Architecture and Digital department of V&A Museum, is at the forefront of showcasing cutting-edge art, science, design and technology. From the very beginning, the V&A has championed pioneering art, science, design and technology. Now in the midst of the digital revolution, this eagerly anticipated exhibition delves into our fast accelerating future of artificial intelligence, synthetic biology and space exploration. The V&A is taking live experiments about our future society from the studio and lab into the museum. Tristram Hunt, Director of the V&A, said.

Mariana Pestana and Rory Hyde are the curators behind the exhibition. Mariana Pestana, an architect and curator, is also one of the co-founders of the collective The Decorators and Rory Hyde, a designer, curator and writer based in London, is currently the Curator of Contemporary Architecture and Urbanism at the Victoria and Albert Museum. He has been at the V&A since 2013, where he has curated the exhibition All of This Belongs to You (2015), and he is also part of the team behind Rapid Response Collecting.

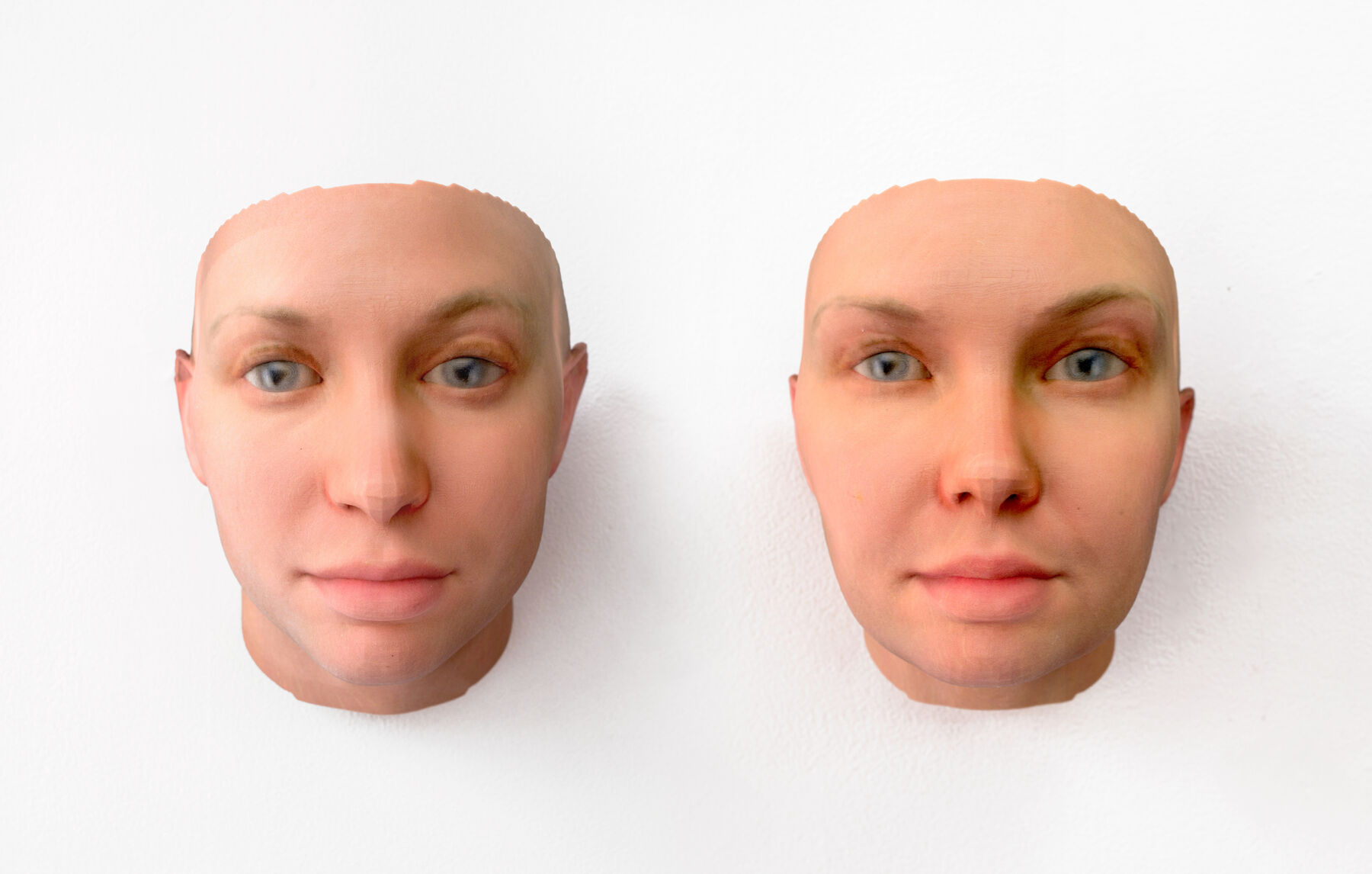

The Future Starts Here is divided into four themes: Home, Public, Planetary and Afterlife. It includes pioneering artists such as Heather Dewey Hagborg, Pauline van Dongen, Jalila Essaïdi and Tomás Saraceno, together with specially commissioned works by Miranda July, Stamen, Tellart, Marco Ferrari and Kei Kreutler. How does digital connectivity affect our relationships and privacy? What alternative ideas and services do we have to improve public services? How do we give access to space to individuals (and not only astronauts), and how do we mitigate the threat that both the natural world and the human race are facing? These are some of the roads that Pestana and Hyde want us to explore.

The line between the digital and physical worlds is becoming more and more blurred these days. How we relate to technology and the impact it may have on our lives and the planet is questioned in The Future Starts Here, which will run from 12 May to 4 November 2018 in the Sainsbury Gallery at the V&A Museum in London.

The Future Starts Here will explore the power of design in shaping the world of tomorrow and will bring together ground-breaking technologies and designs currently in development in studios and laboratories around the world. Could you tell us a bit more about the intellectual process and the concept behind its inception?

We introduce the exhibition with a quote from the philosopher and urbanist Paul Virilio, who says, ‘The invention of the ship was also the invention of the shipwreck.’ The idea is that all new inventions and ideas contain both good and bad futures within them. This show is about examining today’s new technologies and designs to see where they might take us next. What futures do they contain? Are these futures that we want?

For example, we will be showing a driverless car by Volkswagen. While we’ve heard a lot about this technology, very few people have actually seen such a thing, let alone been inside one. We will give you that experience as a way to ask where this technology might be taking us. What impact will driverless cars have on cities? Will they lead to more traffic or less? If all of these new vehicles are electric, that promises to transform the air we breathe, but there are still big questions around cars that can make decisions with little human input.

By asking these kinds of questions, we are suggesting that the futures contained within these things aren’t necessarily fixed. While technology today is often discussed with a sense of inevitability, we are eager to show visitors the part they can play in shaping how these ideas develop and that they still have a voice. That’s what we mean by ‘The Future Starts Here’. These are all ‘starts’. They are beginnings, and it’s up to us to decide where we go next.

What was the biggest challenge you faced in its development?

In putting together this exhibition, we’ve travelled the world, visiting companies, research labs, universities, institutions and designers’ studios. Each time, we ask them, ‘What’s next?’ We’re looking for the thing they’re working on now, the thing that’s on their desks, as opposed to the one they’ve just released, for example. So, in many ways, this is a traditional V&A exhibition in that we’re telling a story through physical objects. But unlike many of our shows, which are focused on established designers, or important historical art movements, these things have never been seen before, and we may not even have the eyes to see them.

For example, a Bitcoin miner is one of the most fascinating objects of technology and design today. On the one hand, it’s ugly, almost ‘undesigned’, just an exposed circuit board, USB mining keys, flashing LED lights, and a bunch of cables. But on the other hand, it’s beautiful, an unadorned expression of the networked world, and how this network is being transformed by new kinds of distributed software.

The challenge for us is to make these kinds of things come alive for visitors who may never have encountered such a thing. That’s why we have used questions as a tool to structure the exhibition – ‘What makes us human?’, ‘Does democracy still work?’, ‘Who wants to live forever?’ and so on. The purpose of these questions is to make the link between the thing you haven’t seen before with your own life. They suggest how these things are poised to transform our everyday lives and why you should care about them.

In The Future Starts Here, the increasingly blurred lines between humanity and technology will be examined with projects such as powered clothing company Seismic’s ‘super suits’. In which ways do you think are interactive and digital technologies changing or affecting human behaviour?

One section of the exhibition is titled the question, ‘We’re all connected, but do we feel lonely?’ Here we are explicitly looking at this relationship between people and technology. The photographs by Iranian photographer Hanif Shoaei tell this story very clearly, depicting people in bed staring at their own devices while seemingly ignoring the person next to them.

These images seem to convey this sense today that digital technology is pulling us apart, despite claiming to connect us. Other images in Shoaei’s series break this simple binary, but certainly, that’s how many people feel about technology today.

Superflex’s powered clothing is also a part of this story, particularly as the product is pitched at the elderly. This is a technology designed to extend the physical capacities of older people by providing extra power in the legs and back to assist with simple movements such as getting up out of a chair or maintaining good posture. This can allow older people to continue living independent lives and to age in place rather than be moved into care. The design is soft, elegant, and not at all ‘technological’, the kind of thing you might invite into the home.

The Future Starts Here will consider scientific solutions to the prospect of immortality. Around 2,000 people worldwide have signed up for life extension services, to be stored in liquid nitrogen after death, with a view to being brought back to life in the future. How do you imagine the future of the human species?

That’s the big question! The idea of extending your life, or even being reawakened after death – as Cryonics promises – is one of the most fascinating areas of futurism today. It’s where science fiction crashes into ‘science’. Obviously, it’s completely untested, so it’s hard to know whether to take it seriously, but many clever people have signed up for it. Anders Sandberg, a professor at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute and one of our advisors to the exhibition, is a subscriber. The way he describes it is almost like, ‘why not?’ If there’s a chance you will be reawakened, even a very small one, wouldn’t you take it?

But this literal preservation of the individual is an extremely selfish future to believe in. As another of our advisors, the anthropologist Arjun Appadurai, said, ‘Cryonics is the opposite of organ donation’. So we are also presenting what might be considered more ‘generous’ ways to live forever. These include the preservation of genetic material, such as the Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, an island off the coast of Norway, or through the preservation of knowledge and ideas, such as the Library for Civilisation by the Long Now Foundation, which we will be recreating in its entirety.

What does the V&A want to bring to the audience that interacts with this exhibition?

In putting this exhibition together, we’ve found that people tend to feel anxious about the future. They feel it’s something done to them rather than something they have a part in shaping. That ranges from the banal, like when Apple changed their charging plug, to fundamental questions of democracy, such as how social media is used to influence elections.

By showing the real things, what we call ‘evidence of the future’, we want to help visitors to make sense of these technologies and ultimately show how they can change them. So in that sense, the exhibition is really about agency, about the power we have as citizens, as a collective, as a species, to shape the future that we want.

We will be presenting projects by all the big tech companies Apple, Google, Facebook and Amazon – as these companies are heavily invested in shaping the future – but alongside, we will also show what we call ‘counter projects’, things which are open source, crowdfunded, bottom-up, often from other parts of the world, and which present an alternative to this monolithic Silicon Valley idea of the future.

For example, we’re showing an architectural model of the new Apple HQ designed by Foster + Partners, a pristine spaceship in a perfect circle, as finely detailed as an iPhone. This will sit next to a full-size section of the Luchtsingel, a pedestrian footbridge in Rotterdam designed by ZUS architects that were crowdfunded. One is made of aluminium and glass. The other is made of rough-painted timber. Both represent equally compelling and yet very different futures for architecture.

What would be your biggest curating extravaganza?

That’s a tough question, but I would have to say this exhibition is it. We are showing the largest object ever in the V&A, the Aquila unmanned aircraft designed by Facebook. This is a prototype for a future fleet of aircraft flying in the upper atmosphere, beaming the internet down to an entire continent.

It has a 40m wingspan, which just fits inside our new gallery, corner to corner. That alone is worth coming to see, and we have 100 other things too.

You couldn’t live without…

The sun.