Interview by Lidia Ratoi

ScanLAB is a tale of a meeting between two worlds, brought to life by two architects. One story is that of the existing reality. One is that of reconstructing and reinterpreting said reality. It is humane and natural to overlook things. Even forget them. Take buildings for granted. Cities as a given. Streets as simple addresses. In the grand scheme of things, details are futile. Our eyes go beyond the details into the banal. Our eyes. But the beauty of today’s world is that it doesn’t only have to be seen through them – in a reverse way of creating art, ScanLAB turns to the real instead of the imaginary through the eyes of a machine.

They turn temporary moments and spaces into compelling experiences, images and film by using 3D scanning as the primary means. View things in detail. Use the logic of the machine. Their projects range from one theme to another. From one place to another. From online environments to immersive installations and objects. From their own particular architectural-inclined approach to that of scientists, artists, broadcasters or journalists.

In the book Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, Marco Pollo poetically describes the cities he’s seen to a bored emperor by the name of Kublai Khan. ScanLAB used the same poetic sensitivity with their own Invisible Cities, a journey through Italy aiming to rediscover forgotten places through new technology. In the Bay of Naples, they scanned frescos underwater using sub-sea LIDAR techniques. In Venice, they scanned the canal from a moving boat. In Florence, they switched to mobile, backpack scanning of the Vasari corridor.

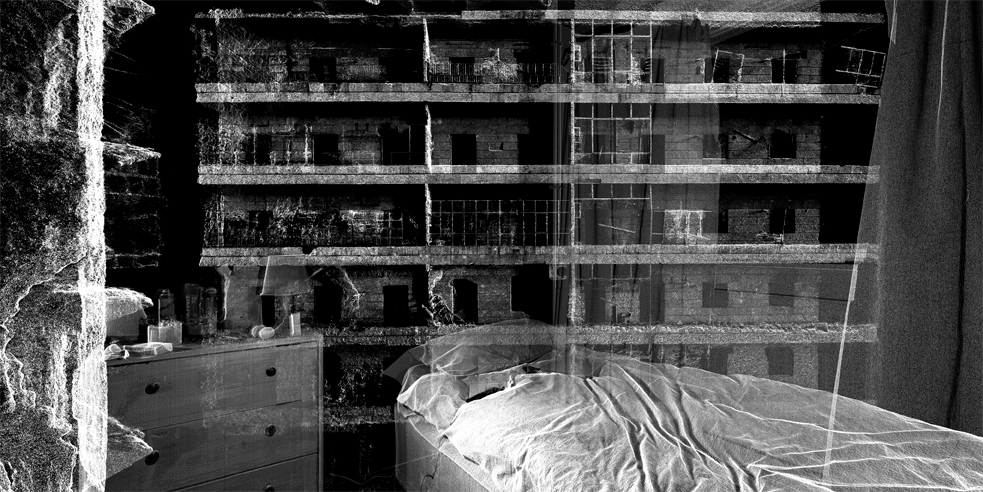

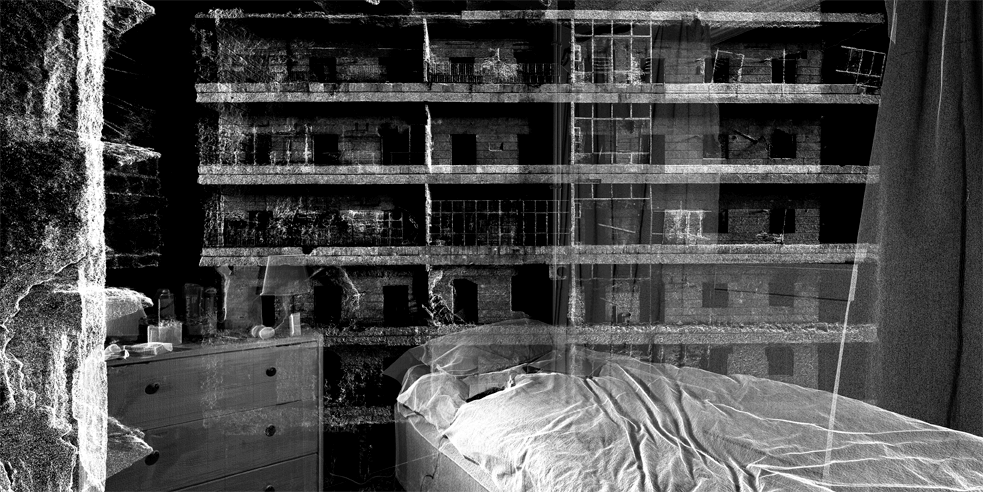

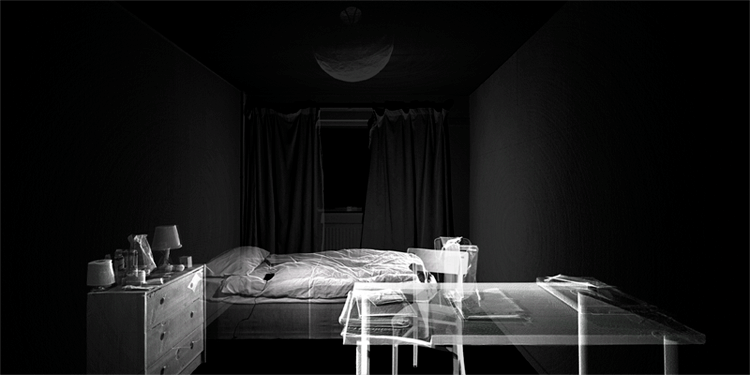

By scanning, re-assembling and reinterpreting reality, they take the users through worlds of the senses. With every scan, a story. With every story, a visual style matches it. Sometimes, the worlds created are worlds of supreme happiness. Other times, they are hard-to-take-on situations. Projects such as Limbo make you think of what it is like to flee your home and start all over in a new country. It tells the tale of those who live with 5 dollars a day while they are waiting for political asylum in the UK. It shows and makes you feel the real-life Limbo some have to endure.

ScanLAB is unique in the very fact that it does not need to invent anything that wasn’t already there. You see, the trick is to look at things in a way you haven’t before. To feel things you wouldn’t normally have. And luckily, machines can help you do that.

You have a background in architecture, and ScanLAB specialises in exploring the use of large-scale 3D scanning in architecture and the creative industries. For the ones who are not familiar with your work, could you tell us a bit more about it? How and when does the interest in incorporating laser in your practice come about?

We both (Matthew Shaw and William Trossell) studied at the Bartlett School of Architecture (many years ago now!) with the intention of becoming Architects. Whilst in our Masters, Faro (one of the leading manufacturers of Laser scanners) lent the Bartlett one of their LiDAR scanners. At the time, these were £100,000 instruments, so it was quite a privilege to get our hands on one. It was a hell of a bit of kit and took a fair bit of head-scratching to get it all working, but as soon as we saw the first scan load across the screen, our minds were blown, and we immediately set about focusing its all-seeing eye on everything from smoke and mirrors to nude figures.

Using these digital simulations of reality, we’re able to re-construct worlds of almost infinite detail, and over the past few years, we’ve collaborated with an extraordinary range of people from sea-ice scientists to film and documentary makers to Museums and Institutions around the world. As two people with roots in crafting the physical world, scanning has always been the gateway and mediator between these parallel worlds. Its fundamental unit of resolution – the point – is just an evolution of the pixel soon to be so dense and quantised that the two will eventually be indistinguishable.

What is the project that is keeping you busy at the moment? Could you tell us the intellectual process behind it?

Post-lenticular Landscapes is a re-enactment of the early photographic expeditions of Watkins, Weed, Muybridge and Adams into Yosemite National Park. Our expedition, in the Summer of 2016, was not equipped with cameras but instead with the latest terrestrial laser 3D scanning equipment. The completed work – a high-fidelity 3D hologram of Yosemite Valley – was displayed at LACMA in Spring 2017.

In the 1870s, Eadweard Muybridge looked to Yosemite as a setting to test his pioneering photographic techniques. These early expeditions have been replicated throughout history, most famously by Ansel Adams, but more recently by thousands of digitally enabled adventurers with comparatively tiny cameras tucked into their pockets.

Post-lenticular landscapes re-enacted these expeditions equipped with the very latest in terrestrial laser scanning technology. This crusade has unearthed the three-dimensional facts of the landscape, allowing the photographic experience of Muybridge, Adams, and a thousand other visitors to be digitally replicated and realising Muybridge’s original endeavour to capture the scenes in three dimensions as stereograms.

What has been your most challenging project, and why?

On a technical level, Limbo was one of our most challenging projects: new software, rendering engines, workflows and capture techniques were all needed to pull this off. We started with scanning sections of Manchester using mapping techniques usually employed by Google for mapping cities in enough detail for driverless cars to navigate within.

However, we adapted the technology so we could re-imagine these spaces as imposing generic cityscapes. We also needed to develop a way of rendering and animating the playing back of people we captured with Kinects, to populate this Limbo landscape. Combined with huge 8k renders and stereoscopic compositing & Ambisonic 3D sound, it was quite a journey.

You have developed a few projects with a sociological angle (Displaced Witness, Crime Scene, Limbo..) with the rise of disciplines like Forensic Architecture, what impact do you see your practice may have in the development of these new disciplines?

We don’t see these as particularly new disciplines. Bearing witness to events is often the assignment of photography. And we are all too aware of how the timing of a shutter release can distort interpretations of those events. Film and moving image add dimension to those difficulties, and scanning adds yet more. But development in technologies which augment our senses has always driven new understanding and perception.

Exploring these concepts and the lives of those we’ve captured are central to the sense and placement of the work as a commentary on this emerging media, and as the role of Journalism is being questioned globally at the moment, we think these are important areas which need to be explored.

Utilising scan data in the Forensic capture of a crime scene has huge applications in sciences and humanitarian investigation. Capturing everything quickly and at extreme resolutions locks evidence securely in a digital world to be examined hours, months or even decades later. We’ve worked alongside fire rescue teams as well as Forensic anthropologists and entomologists to aid investigations and research. All of these have benefited from the scanner’s ability to document space in meticulous levels of detail, which far exceeds what is humanly possible with tape measurements and sketches.

We’ve collaborated with Eyal Weizman on a number of interesting projects across Bosnia and Serbia looking for evidence of activity above and below the ground stretching from events connected to the Second World War right up to present-day occupation.

Where would you like to take your work into?

Outer space.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

A mess.

You couldn’t live without…

A sense of curiosity.