Text by CLOT Magazine

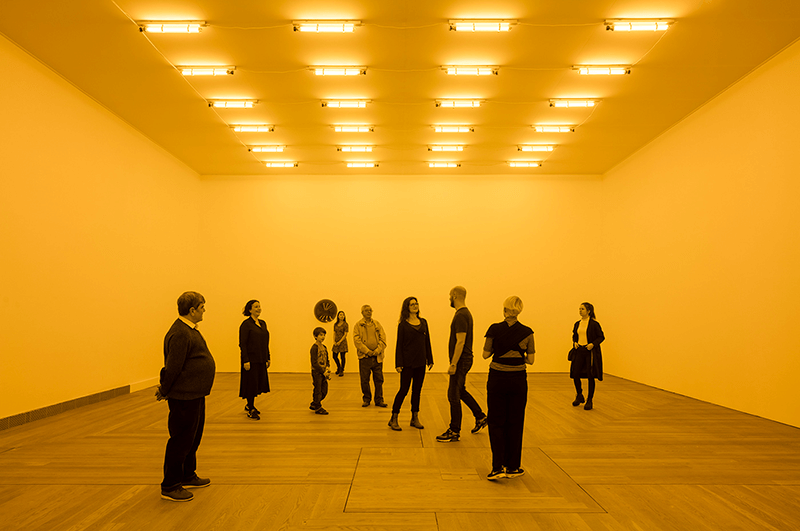

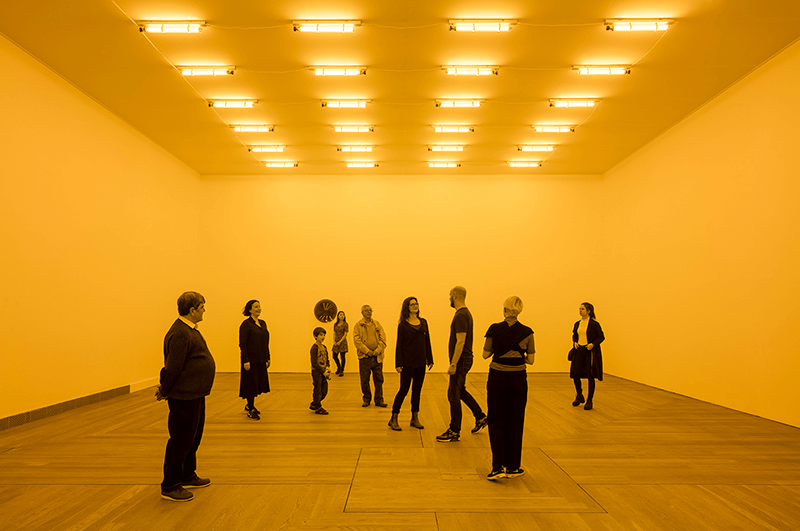

What happens when you find yourself in a room where all the sense of colour reduces to one? You can experience this mind-altering phenomenon in a Room of one colour (1997), a light installation by renowned artist Olafur Eliasson [1]. The piece is part of the exhibition Monochrome: Painting in Black and White, currently running at the National Gallery until 18 February 2018.

Artists intrigued by colour theory and the psychological effects of colour (or its absence) manipulate light, space, and hue to trigger a particular response from the viewer. This exhibition reveals the use of colour as a choice rather than a necessity.

As curators Lelia Packer and Jennifer Sliwka explain, artists can reduce the use of colour “mainly to focus the viewer’s attention on a particular subject, concept or technique. It can be very freeing – without the complexities of working in colour; you can experiment with form, texture, mark making, and symbolic meaning.” National Gallery Director Dr Gabriele Finaldi also shares that artists choose to use black and white for aesthetic, emotional and sometimes even for moral reasons.

In Room for one colour, sodium yellow mono-frequency lamps mounted to the ceiling of a white room emit yellow light that reduces the viewers’ spectral range to yellow and black, all other light frequencies are suppressed, and visitors are transported to a monochrome world.

This colour trick creates an involuntary neurological response that intensifies the participants’ perception of detail and dimension. Grain, depth, shape and contours acquire a completely new dimension and even sense. After leaving the space, there’s a reaction to the yellow environment, and viewers momentarily perceive a bluish afterimage reflecting the readjustment of the eye cones to a broader spectrum of wavelengths.

As part of the parallel events complementing the exhibition, Olafur was in conversation with Jennifer Sliwka, one of the curators of the exhibition. The talk went over some of his most famous pieces, such as The Weather Project in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern (2003), the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion (2007), a temporary pavilion designed by the Norwegian architect Kjetil Thorsen, and The New York City Waterfalls (2008).

Olafur also discussed with Jennifer the cultural role of institutions and how art is exhibited in these special places, how the audience engages and uses the space, awareness of environmental issues, light and colour from scientific and artistic perspectives. Olafur ended the session by pointing out what his Research lab is interested in at the moment: circadian rhythms and light regulation of human bodily functions (earlier this year, Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W. Young were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017 for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm).