Interview by Christopher Michael

Daniel Van Lion is a composer who is unafraid of experimentation in all its forms. For example, UVVA, his second full-length release for Menta Records, plays with devotional and sacred music, blending classical influence with electronic elements to create a sound that is uniquely his. Like much of his larger body of work, the album brings listeners to an otherworldly sonic landscape, where a range of influences combines to create a magnetic listening experience. Taking his inspiration from a wealth of sources — the films, the bars, the mountains, the horrors — Van Lions has created an individual sonic universe which continues to challenge and impress audiences.

Van Lion’s experimental approach is put on full display in his new single, Weak, a collaboration with Washington-based musician Atomfagott (aka Noah Michael Smith). The track was produced during the pandemic, born out of Skype meetings and online exchanges during months of lockdown. Both Van Lion and Smith come from similar musical backgrounds, having an appreciation for the traditional and academic music scenes but curious to push sonic boundaries. In addition, each artist shares a similar attitude toward their music, blending both “high” and “low” influences within their work. Van Lion put it best when he said they could both feel the same admiration for a Baroque piece as for a Shygirl song. This dedication to music in all forms can be seen in Weak, the varying influences playing together to create a distinctive sound.

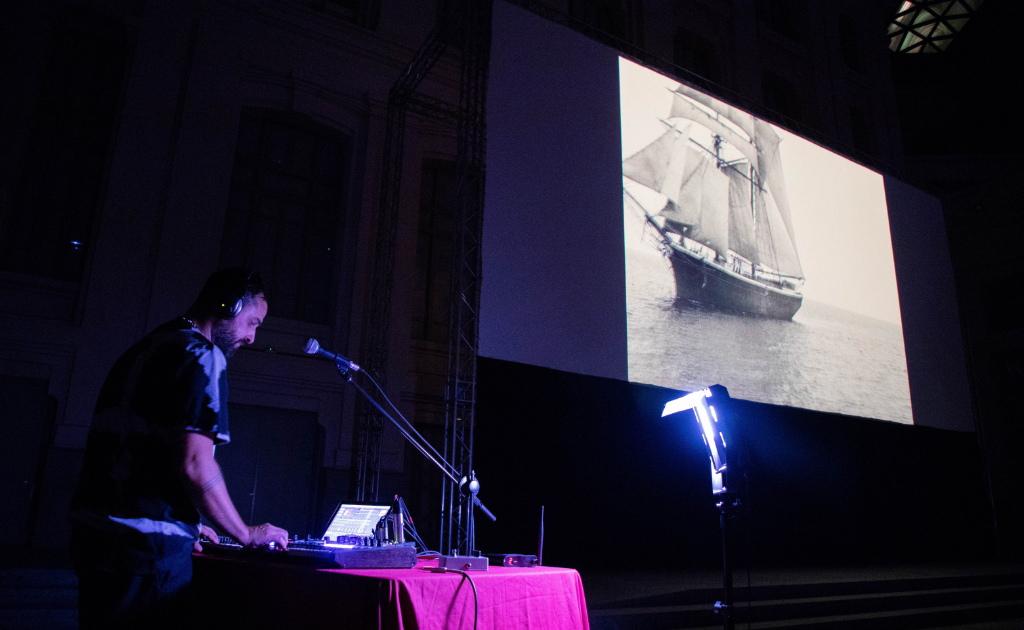

Van Lion has also been working on a new score for the 1922 F. W. Murnau film Nosferatu for the past year. Commissioned by mk2 Cinemas as part of their CINETRONIK movie series, Van Lion aims to bring new life to the film on its 100th anniversary.

For a composer who works largely from images and whose music has a certain cinematic element, it was fitting that he was chosen to produce a soundtrack for the legendary film. Approaching the project with a sense of freedom and drawing from his DIY spirit, the soundtrack has pushed the boundaries of Van Lion’s practice, taking his sound to new places. Combining the century-old film with Van Lions’ distinctly contemporary music was a challenge, yet it has resulted in an unconventional, though highly enjoyable, piece of work.

Weak is an unstructured avant-pop cut that functions in the experimentation and fusion of genres with ambient, post, world music and industrial elements. Sonically speaking, how was its conception and its relationship with your previous productions?

I produced this track during the pandemic after meeting Noah Michal Smith. The fact that it was created in confinement, in those days of introspection that these years have given us, has had a lot of weight in the result. It is said that the blows in life lead to creating things that are more honest with oneself. I think something like that happens with “Weak”. It was a song composed without any kind of pressure and with no other ambition than to keep my head busy in the studio for a few hours a day. It is also a song born from the beginning of a long-distance friendship, from fears shared via Skype and the desire to experiment with creating something together.

Has there been any radically changed aspect of your work in the evolution of your musical process in your upcoming release, Weak?

The most different thing has been to start shaping it from a vocal stem with a theme already given by Atomfagoot (the lyrics are a version of a poem by a friend of theirs who had passed away some time ago). Otherwise, the process has been quite similar to what I always do: I create images in my head and play with sounds. Sometimes it happens the other way around that a melody or a percussion rhythm takes me to a space where I feel like investigating further. The process is usually very intuitive. At least before moving on to the final arrangements and mixing, which is much less fun…

As for the more formal part, “Weak” is a down-tempo track where I play a lot with silence. I don’t know if this might have something to do with the fact that lately, I’ve become very interested in traditional music again, be it African, koto, flamenco, and tarab. I have also been listening to a lot of sacred music, where the spaces are almost as important as the sound parts. It is curious that songs pass from generation to generation in popular music without musical accompaniment. Either there is voice or silence; the rest you create in your head. It seems to me an exciting starting point.

In Weak, you collaborate with musician and vocalist Atomfagott. How did you approach the creative agency in this collaboration? And how do your individual background influence each other?

Noah and I met through a mutual friend. In addition to being a vocalist, they are a church organist and an ambient and experimental musician. Both of us have known closely the more academic side of music, that of conservatories, of professors who decide what is and what is not music, what is well performed and what is not, etc. Your grade at the end of the year dictates whether you are a good or a bad musician. Although I admire these spaces very much, they are necessary for many reasons; when you are curious, you have to look elsewhere. It’s not characteristic of music; it’s the same with fashion, literature or painting. Noah and I can feel the same admiration for a Baroque piece as for a Shygirl song, and that’s what has united us the most, even though we have never met personally (they live in Washington, and I live in Madrid). Beyond our differences in tastes, we vibrate in similar frequencies.

For the past year or so, you have produced several remixes, explored the field of performing arts and composed a soundtrack for F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu. What’s the soundtrack’s core idea and sonic intention, and how does it relate to your creative process?

Setting “Nosferatu eine Symphonie des Grauens” to music has been inspiring and rewarding in many ways. I am very grateful to MK2 Cinemas for the initiative. Musicalizing a film is a very particular process; it’s as if you suddenly become part of it. You see it over and over again, and in the end, you end up getting something out of each character; you feel more empathy for some than others or even identify with them. When I compose, I tend to be very conceptual; I play a lot with images, allegories, etc. Creating a soundtrack ex profeso for a film or a stage piece is like working with images that come from the outside. However, although they are given to you, your interpretation will always be unique since there is no piece with a single reading.

On the other hand, there has been a lot of synesthesia in the whole process. The film is divided into acts, just like an opera, and contains scenes in different tones directly related to the mood of that part of the story. These emotions can be enhanced when you align the music in the same direction. There is some cheating; I have to admit. But in the end, that’s the magic of fiction, isn’t it? However, I tried to create a score that, while it has more intense parts, didn’t tarnish the story with too much epicness. I was afraid of going overboard but also of coming up short. In the end, as for the bulk of the work, I highlight the freedom I have allowed myself to approach the project. Here I sing, play the guitar and even clap my hands! It has helped me to bury a lot of insecurities.

Your future projects will delve into IDM and industrial electronics with live instrumentation. How would you describe your aesthetics today, and how do you see it developing in the future?

I wouldn’t call it IDM, although I don’t know how to qualify it either. Now I’m composing some new tracks for a work inspired by medieval music. At the same time, I’m starting a project with a saxophonist, with whom we want to continue exploring that communion between current production techniques and other older genres such as jazz, concrete music, etc. I am increasingly interested in everything that has to do with the stochastic process in music that Xenakis talked about, where the composition is influenced by predictable actions and random elements linked to one’s own experience and intuition.

Is there a way to listen to your work that you consider ideal? What is the most appropriate way to prepare to listen to your work?

Any! The reception possibilities are endless and have a lot to do with the person, their background or the day they have had at the office. In my case, for example, I enjoy music in the car. It is possibly where I pay more attention to what I hear. Although if I have to choose, a concert in a natural context also seems to be a good setting.

What are your main inspirations for your productions these days?

I get inspiration from many places, in the films, the bars, the mountains, and the horrors. I still listen to many old records by Coil, Scott Walker, David Lang, Dead Can Dance, Basinski or Arthur Russell, but I also like to discover new things that influence me. Lately, I’ve been very interested in what artists like Kali Malone, Abul Mogard or Heith are doing. Still, I’m more inspired by the images than by the music.

What is more important: to take or not to take yourself too seriously to be creative?

You must take yourself seriously when creating, but never as a creator. If you don’t take yourself seriously, who will?

One for the road… What are you unafraid of?

To contradict myself.