Interview by Agata Kik

Born in Athens and based in London, Dr Eleni Ikoniadou is an academic, writer, theorist and curator. Previously in the role of a founding director of the Audio Culture Research Unit at Kingston University, a platform exploring the digital and sonic aspects of culture, and Executive Board Member of the London Graduate School, Ikoniadou is now a Reader in Digital Culture and Sonic Arts and Senior Tutor in Visual Communication at the Royal College of Art, London. Her research brings together art, theory, and technoculture, with a specific focus on sound and voice.

In 2019 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, she curated Her Voice, an evening of live performance, sound, film and discussion examining the ubiquitous nature of automated female-sounding voices in contemporary life, proposing an inquiry into the question: How might we test mainstream notions of agency and subjectivity, manifest alternative productions of knowledge and power, and acquire new understandings about what it is to be female—or, even, what it is to be human—under the spell of ‘her voice’?

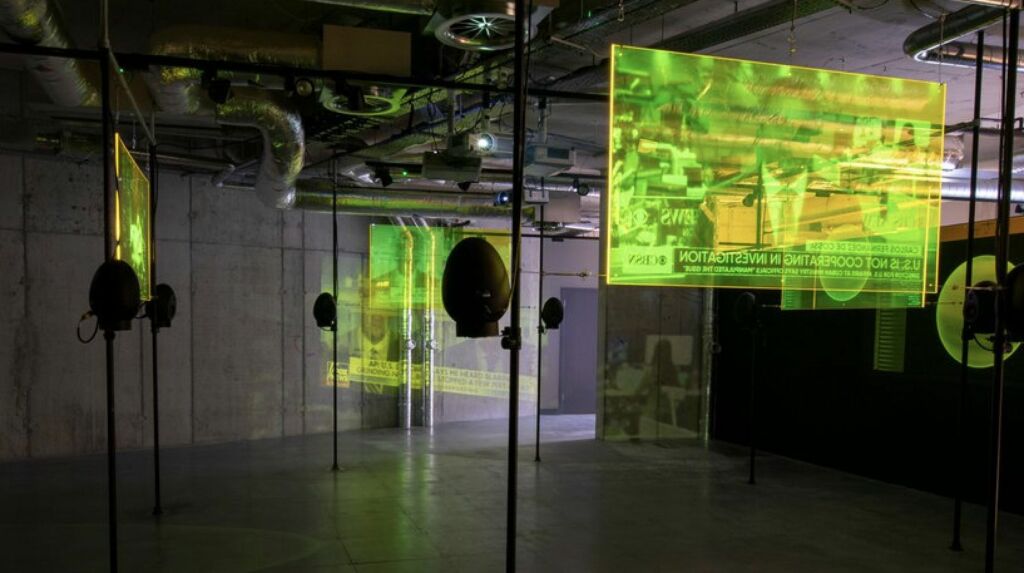

She is also the author of The Rhythmic Event: Art, Media, and the Sonic (MIT Press, 2014), in which she suggests the notion of rhythm as a way to tap into the nonhuman modalities of accessing an event of knowledge. As a member of the art research group AUDINT, researching peripheral sonic perception, together with Steve Goodman (kode9) and Toby Heys, they co-edited the anthology Unsound:Undead (Urbanomic/MIT, 2019). Evoking the potential of sound, infrasound, and ultrasound as interdimensional carriers, they inquired into inhabiting the space in between the realms of the living and the dead. Unsound:Undead also turned into an exhibition presented in 2019 at arebyte Gallery in London.

Ikoniadou is a resident host on the show Fugitive Voices on Movement Radio, a series of conversations with guest artists and theorists such as Season Butler, Lee Gamble or Jenna Sutela. Most recently, further exploring the idea of the ‘fugitive voice’, Ikoniadou curated a compilation of sound works titled Future Chorus, released by Hypermedium and MAENADS.

Future Chorus draws on Ikoniadou’s previous project Polyphonic Intelligence, asking how to move beyond the boundary between human and machine subjects and producers while exploring Machine Learning techniques for composition, performance, and broadcasting—funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, under the Art, Music and Culture programme of Human Data Interaction. Future Chorus has brought together diverse artistic voices into a shared exploration of Ikoniadou’s polyphonic inquiry into the voice.

For Ikoniadou, these females, animal, artificial and inanimate voices, lamenting, screaming, dreaming, and mumbling, conceal an emancipatory potential for a paradigm shift within the current social system and its culture. We need to look to other paradigms—feminist, indigenous, queer, and disability studies approaches—where the singular idea of the human as a rational-speaking animal is exposed as an outdated and invalid category. Through her practice, Ikoniadou condemns the patriarchal traditions and rationalisation doctrine, which originates back in ancient Greece, where marginalised voices within society were claimed to hinder man’s search for harmony and truth.

What does it mean to be curating an art publication in the form of a sound album? What did the process of creative collaboration with the involved sound artists behind Future Chorus look like?

This project ended up being a record mostly out of necessity, as this was decided during lockdown when I couldn’t share the findings of my research with an audience in the form of an installation or performance, as was the initial plan. Making an album was an interesting new experience. I usually work across different formats, fields, and practices—often in collaboration—according to what needs to be ‘said’. Making an album communicates this very differently to an exhibition, a book, or a talk; the scale, speed, reach, and capacity of a thing to enter into a dialogue with others change completely depending on the form. But more important is the encounter with these ‘others’ (whether human or not), the different ways of thinking and modes of being that they enable and what is produced from the interaction. Form is secondary.

Generally, I don’t love directing others, and I’m opposed to hierarchical structures of any kind, which is why I was drawn to working with the chorus as a conceptual, methodological, and sonic device. In an ideal world, this project wouldn’t be presented as only mine, and I wouldn’t be the only one doing this interview right now. For practical reasons, I am hoping to channel or convey something of the other voices as I go along.

Working with the involved artists was like any other collaboration, sometimes smooth, sometimes not, with the added complication of never having met, working remotely as we did, from around the world during the lockdowns. I’m proud of the result, but I’d change some things if I could. I regret not thinking of including Sukitoa O Namau’s lamentation ‘Animal Grief’ as one of the music tracks on the album. Other than it’s a brilliant piece, it was she who brought the idea of animal voices + AI to the chorus, to begin with, and this should also have been credited appropriately on the sleeve not as a ‘human voice’ but as ‘animal lament’. I’m looking for a way to make this right.

Could you please describe some of the inspirations that led you to put Future Chorus together? What were the selection criteria for the material fed into the vocal generation algorithm?

Future Chorus is the outcome of a funded art project called Polyphonic Intelligence. I was thinking about the history of the female-sounding voice—its use in public, in early sound recording technology, automated speech and voice recognition—and in particular about the linkages between female voice, technology and otherness from the prism of polyvocality/ polyphony. Polyphony is a concept borrowed from the field of music, literally meaning multiple voices, and, after the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin, refers to the interaction of many voices unmerged into a single perspective and unsubordinated to the voice of an author.

Following Bakhtin, truth is not found inside the head of an individual, it is born between voices collectively searching for truth, in the process of their dialogic interaction. So this is a key influence. But also, in there, is Nietzsche’s tragic chorus—the act of the individual submerging her identity in the chorus as the only way to come to terms with existence—and too many other literary and theoretical references to go into detail here, such as Anne Carson, Nicole Loraux, Nazan Üstündağ—on female voice, grief and mourning mothers against the state. Édouard Glissant, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, Saidiya Hartman, Sylvia Wynter, Euripides, are all there.

Musical influences are obviously equally important and impossible to go into here. As you may have guessed, experimental electronic music is key, with a soft spot for the UK’s leftfield underground scene of the past five years, especially Southeast London and my adopted hometown of Lewisham (nurturing geniuses like Kwake Bass and Coby Sey). I’m also influenced by radical art and music projects that work as decolonising platforms—like Chino Amobi’s NON with Nkisi (Melika Ngombe Kolongo) and her current research project The Secret Institute or AGF’s (Antye Greie Ripatti) REC:on platform. My head was also in experimental vocal ensembles like Roomful of Teeth and the brilliant Caroline Shaw.

The choice of the laments (human voices, cello, animal), which were collected in the first part of the project and used to train an algorithm to create a new artificial voice, was based on the contributors’ response to my call—almost everyone who responded offering laments joined in—and also I approached a few artists whose work I thought was relevant. As these things go, some decisions are conscious, but most of the time, you follow a line, something unknown and incalculable that is outside a self, in the space where something is activated beyond individual aim and ambition.

Looking back, I can see not so much a criteria-based selection but some connection to fugitivity that glues together all the people involved. For Moten and Harney, fugitive study is “what you do with other people…talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice

What, in your opinion, working with AI and machine learning can bring to our current understanding of what it means to be a human being?

Aside from its technical achievements, AI has imposed the idea that a machine can perfectly imitate human skills, such as emotion and intelligence. To me, it’s not interesting to be for or against these developments. Away from ideas of human-machine equivalence or algorithmic superiority, I’m interested in practical and theoretical explorations that might bring forth new notions of subjectivity, intelligence and identity, currently unimaginable.

I think asking more interesting questions than are currently being asked about technology might help us get there. For example, what possible futures can we imagine for the coexistence of human and artificial voices, and what do they sound like? Your research and curating practice have dealt with the idea of voice extensively. Could you please share what emancipatory potential for an individual and revolutionary promise for the social system you find in the voice that is unintelligibly ‘non-human’? Where does the meaning of voice that is stripped down from language lie for you?

Voice has always played a vital role in human culture. Although there is literature and artistic experimentation on the constitution of the voice (whether human or synthetic), there is a curious gap in addressing the relationship between human and digital voices in new and future-facing ways, helping us to challenge old definitions.

The human fascination with voice and what it means for our ‘humanity’ goes back to ancient Greece. For the Greeks, voice without speech is irrational and not to be trusted. This is commonly associated with female, animal, and nonhuman vocal emissions jeopardising man’s search for harmony and truth. This patriarchal view is at the root of Western definitions of both voice and intelligence. We need to look to other paradigms—feminist, indigenous, queer, and disability studies approaches—where the singular idea of the human as a rational-speaking animal is exposed as an outdated and invalid category. Certain vocalities are entangled in nonhuman history. Having been omitted from humanist political economy and denied subjectivity or a self, they are ideally positioned to tap into and mobilise the alienness and otherworldliness of the human as a category. They open up the way to nonhuman thinking.

What futures do you envisage in your curatorial practice and research work? What could a chorus of the future be? Do you have any speculations on future trends in collaborations between artists and scientists? Where do you see the role of science and technology within the arts in the future?

As mentioned above, for me, the ‘what’ is less important than the ‘who/ how/ and for whom’, as well as the ‘what if’—the speculative probe that fires up new ways of thinking. I am interested in non-anthropocentric, non-anthropomorphic and nonhuman futures, which in many ways, are the most invested in caring for marginalised and dispossessed humans in the present.

As we learn from Octavia Butler, Drexciya, and Kodwo Eshun, to name a few, breaking with this world, refusing to be domesticated or named, whether out of necessity or choice, carries with it the potential to open up a speculative space for the reimagining of the human condition, and for questions of becoming, origin, and futurity. A chorus of the future is concerned with contaminating the factual record and unleashing the untold tales of a people yet to come.

The conversational and community practices of Abbas Zahedi, the cross-pollinating methods of Jenna Sutela, and Adam Christensen’s blurring of the boundaries between everyday life and fiction, are all good examples of the power of art to connect people, fields, and levels of reality. I also appreciate working with new technologies that challenge Western systems of thought and communication (you’ll find many examples of that every year at MozFest).

I’m wary of the art-science-technology trend that pits the arts and humanities as a leftist luxury which only gains value by interpreting, communicating or prettifying tech and science ideas for the masses. Neoliberalism’s ‘innovation’ discourse has infiltrated the art school, and we’re now churning out entrepreneurs rather than thinkers and makers. The only way out I can imagine is the abolition of any one particular institution: the institution called the artist or scholar, or scientist has to be abolished in the interest of a shared aesthetic space. This abolition brings with it the possibility of different models of knowledge; collective, nontraditional, engendering new polyphonic worlds.

To return to the beginning of your question, the only type of work worth doing is the making and protecting of spaces of study, where readings, workshops, walks, dinners, screenings, art exhibitions and sometimes absolutely nothing at all might take place. We need more examples of ways of working and living that diverge from prescribed subjectivities and create an aesthetics of disruption, disturbing dominant culture from the sidelines.

What would be your biggest curating extravaganza?

Future Chorus comes to life as a performance installation exhibition conversation opera club—bringing together everyone involved.

You couldn’t live without…

Lexi and Alva….music is too obvious, and you could probably live without it, albeit a very sad, miserable and painful life, not worth living.