Interview by Christopher Michael

Emmett Palaima is a multimedia artist whose work explores electricity as a divine force, analysing modern technology through an innately spiritual lens. His practice stems from a belief that technology and magic are essentially one in the same, the same force described with different terminology. Drawing on his background in the sonic arts — both as a touring musician and as a designer of synthesisers and guitar pedals — Palaima creates immersive sculptures where sound, and the processes of sound creation, take centre stage. Viewing his work in person is a powerful experience, each piece generating a sense of reverence around the forces of electricity.

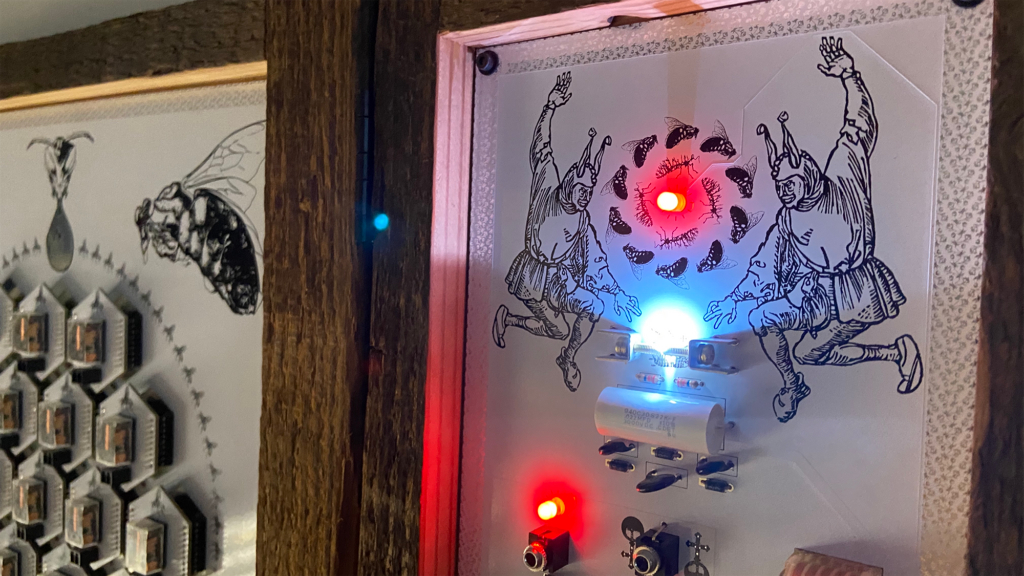

Palaima’s art has recently been featured in New York City and Santa Fe, New Mexico exhibitions. At the Currents New Media Festival [1], he showed Modular Triptych: Great Wurm, a sculptural piece that experiments with electronics and silkscreen graphics on PCB (printed circuit board). The piece utilises mystical symbols of the Ouroboros and the Knave, recurring motifs in his larger body of art. Like most of his work, the sculpture serves a dual purpose, both as a piece of fully functional modular synthesis equipment and an aesthetic object. Utilising the “Shepard tone” — an audio illusionary technique used to create the impression of an infinitely ascending or descending pitch — the sculpture seeks to comment on historical ideas of progress and the passage of time.

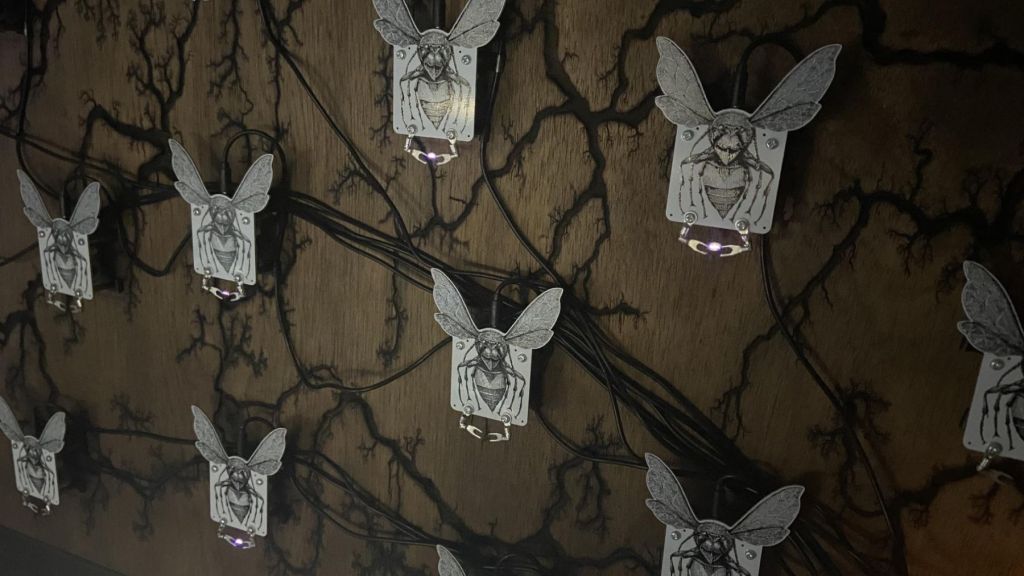

In a similar fashion, Palaima recently presented a roaming exhibition, The Church of the Electric God [2] in New York, which he described as a psychoacoustic spatial drone temple in the back of a (U-Haul). At the centre of this space was his piece CHOIR-64, a psychoacoustic instrument and composition system which broadcast the musical composition Spatial Etude No.1, a long-form generative drone piece where tones change gradually over time. The sculpture highlights Palaima’s belief in sound as a spiritual force and generates a profound sensory experience for those who experience it. Visitors to the The Church of the Electric God were transported out of their immediate reality and forced to reckon with the divine nature of electronics. The meditative chorus of CHOIR-64 drew one into a hypnotic state of worship.

Palaima’s work is conceptually rooted in ideas taken from science fiction authors, 19th and 20th-century mystics, and writers like Jorge Luis Borges. Sound is usually a dominant component, drawing from his musical background but always seeking to create a contemplative space outside of contemporary music culture. His unique blend of influences allows him to create genuinely idiosyncratic work, which transforms one’s perception of their space in truly remarkable ways.

Your practice stems from a belief that “technology and magic are one in the same”. Could you tell us about this connection and how it relates to your work?

The idea is an extension of one put forward by various science fiction authors: as technology and magic increase in power and complexity, they become functionally the same. In both cases, a force we don’t fully understand is harnessed via a ritual interaction to produce a miraculous result, essentially the same type of experience given a different aesthetic dressing.

Our scientific understanding of the world is based on empiricism, observing patterns and repeatable cause and effect. This takes us a long way towards understanding the universe on a functional level, but the deeper it is taken, the more it bumps up against that which simply is. For example, we can begin to understand how a force like electricity functions via repeated observation, but the existence of the force in and of itself is axiomatic a universal mystery.

In my work, I try to approach the force of electricity in these divine terms to restore a sense of dignity and wonder that feels absent from the more utilitarian scientific view. Simultaneously, recontextualising a force and a set of materials that are commonly viewed as commercial, industrial, and utilitarian feels like an interesting lens for analysing our overall relationship to this force and our implicit assumptions about that relationship, which has a bunch of interesting connections to contemporary issues like climate change, globalisation and capitalism. In this way, it’s a project that feels spiritual as well as intellectual and political. It’s a deep topic and one I feel like I could spend a lot of time exploring.

Who (or what) influences your work as it relates to magic/esoteric practices?

I draw on many different sources, including both genuine believers and religious thinkers, as well as those exploring mysticism as a subject for creative practice; Gurdjieff and Jorge Luis Borges are excellent examples of each category.

In Gurdjieff’s philosophy, he explains how the different religious practices of the world function as methods for attaining mastery over the various components of the self, with the Fakir, the Monk, and the Yogi corresponding to the Body, the Emotions, and the Intellect. I love how this recontextualises spirituality as something with real worldly power, a form of technology even, and subverts the view of religion as something necessarily arbitrary and dogmatic.

He also has some crazier ideas about how the universe is arranged in the structure of a descending musical scale (unity being the upper octave and nothingness the lower) and that in this arrangement, the moon is feeding upon the life force of humanity, which makes for fun material to riff on both philosophically and aesthetically.

Meanwhile, I love Borges for his ability to capture the voice of a mythical storyteller and to invoke a genuine sense of wonder in his writing. I also like the ability to freely reinterpret myths and legends to explore a philosophical point without destroying the sense of mystical dignity that makes these stories special. It’s a style and a mood I try to emulate in my work.

In addition to your artwork, you have also toured as a musician. Are there connections between your music and art practices? If so, how do they influence one another?

My artwork incorporates a lot of my experience as a musician while also being a reaction against the many shortcomings of music as a medium in the modern world. In objective terms, music is probably the most powerful artform because it works on our animal senses and produces the most direct and immediate emotional response. It’s also the most accessible medium and functions as most people’s first point of entry into having a relationship with art and creativity.

At the same time, the advent of streaming and the democratisation of music production tools has created a situation where the medium feels over-accessible and oversaturated and a context for music where it largely exists as content for a digital streaming platform. Simply put, under the current conditions, music doesn’t feel special. So I’m interested in using my work as a means to recontextualise the experience of sound in a way where it can feel unique and magical again.

Simultaneously, in the process of working in and around music and the sonic arts, I’ve met a lot of people who are excited about designing systems to create sound and end up making excellent and exciting tools to produce yet another ‘amorphous drone’ or ‘crackly found sound’ or ‘prepared piano’ type piece. I also developed a personal relationship with this while working on audio systems for immersive spaces and designing music gear, where I could see beauty in the systems I was designing that was absent from the eventual result. A big focus of my work is making the system an intrinsic part of the overall presentation, where the object or process creating the sound is as much on display as the sound itself.

You recently had your piece, Modular Triptych: Great Wurm, featured in the Currents New Media festival in Santa Fe, NM. Could you tell us a little about that experience?

Currents was a great experience all around. I lived in Santa Fe for two years, working on immersive installations at Meow Wolf Creative Studios and had my first solo installation piece, ‘Signal Flow No.1’, at the Currents 826 Gallery, both of which were highly formative experiences for my creative identity.

I left New Mexico in February 2020 both for personal reasons and to do a six-month tour of Europe and the US with a band I was in at the time, plans which were curtailed by the pandemic. So I took a big risk on a creative project and on myself at precisely the wrong time, my life got blown up, and I was left to pick up the pieces and figure out what came next. This involved a lot of struggle, but this year as I’m feeling more settled in New York and confident in the direction of my creative practice, it’s starting to feel like the big leap I took paid off for the first time. So on a personal level, it was great to come back to Santa Fe and see old friends; under those circumstances, kind of a come full circle moment.

Regarding the festival itself, I’m all about what Currents does. It feels very unpretentious and focused on the work for its own sake. It is also accessible to younger artists with good ideas but not necessarily a huge amount of exposure or institutional support. There are a bunch of different perspectives on the use of technology in art, and it’s enjoyable to see that all come together in a single space. I met a lot of talented artists, and the staff and organisers were great to work with.

What inspired the Modular Icon series, and do you have plans to expand it?

The Modular Icon series came out the time after I left New Mexico. The experience of working on immersive spaces and doing my first installation piece had me feeling a lot of potentials. Still, a possibility that felt very open-ended and aimless, often to the point of feeling frantic. Simultaneously the pandemic was happening, and I suddenly had a lot of time on my hands to experiment but no access to a public space for a performance or exhibition. Using a circuit board as a visual art medium became a form factor where I could finish work on my terms and still accomplish much of what I was going for.

Once I made this type of work, I found the philosophical implications to be exciting to explore. Much of my current artistic philosophy was developed alongside the production of the early pieces. Combining aesthetic form, electronic function, and narrative meaning to produce these pieces is a pretty intense process on all fronts, so the pace of doing work tends to be a bit slower. I feel like the potential here is nowhere near fully explored. I’ve just scratched the surface, and it feels like something I could keep returning to for years.

Your work has many recurring symbols, like bees, the ouroboros, skeletons, and cicadas. What draws you to this imagery?

I incorporate recurring symbols to build a cohesive mythology and consistent meaning throughout my body of work as a whole. I like the idea of the symbols developing a more profound sense and relationship to one another through constant use and viewers being able to recognise this happening from one piece to another. Additionally, I try to explore the parallels between schematic drawing, the abbreviated visual language of audio equipment, and the symbolic language of esoteric and religious practice to form a sort of combined aesthetic from all three.

Individually, each symbol is carefully selected and conveys a special significance. Bees are used because of their questionable individuality as beings that exist at the exact point of division between animalistic free will and a mechanical system of automatic response to outside stimuli, as well as their position as a pressure point in environmental collapse.

The Ouroboros represents the endless process, eternal becoming, forces beyond human comprehension, and time on a cosmic scale. Skeletons somewhat obviously mean death, but more specifically, death in the tragicomic sense: the entrapment of the individual within the error of creation and the limits of human vision as an inevitable outcome of our mortality. The cicada also represents the limits of human vision, as an animal completing a continual cycle that it will never recognise as such, given its limited experience window.

What is more important: to take or not to take yourself too seriously in order to be creative?

Both are very important, but I would go too seriously at this point in history. We live in a time where the mask is off and ridiculous, and irony feels cheap. Having a sense of humour is essential because I think humour represents a kind of mutual understanding. Still, at a base level, I believe in approaching my work with the sense that I’m doing something important.

This gets pretty personal for me as I view my work spiritually. If I had been born in a different time and place, I could easily see myself being deeply religious, but for better or worse, I was raised in a secular western household and wasn’t given access to that. So my creative practice is a way of filling this spiritual void as something I can devote myself to with a complete and genuine intensity, both as a means of spiritual betterment and as a refutation of the nihilism I’ve often felt in response to our troubled times. In more down-to-earth terms, I think life is much more fun and enjoyable if people get into stuff, which is my version of that.

Solitude or loneliness, how do you spend your time alone?

I’m comfortable in solitude and can often go days or weeks at a time, mainly doing my own thing. But, on the other hand, I need the ambient sense of having a community around me and the assurance that people will still be there when I get back from whatever tip I’ve been on. Sometimes this has created a sense of inner conflict based on messages from society that engaging in certain codified relationships (specifically the nuclear family) is necessary to guarantee one’s long-term social security. Still, I also realise this messaging is rooted in fear rather than something positive, and these days I try to embrace who I am genuinely and trust that doing so will create the type of environment I need in the long run.