Interview Jacobo García

Pregnancy is an underlying motive in The Flower & The Vessel, Félicia Atkinson´s just-released new album. This a theme that has historically been neglected in arts, or at least in music. In 2019 women, both authors and audiences, are pursuing new narratives that reflect their experiences, motivations and desires. From all over the world, stories that define the emprise of existing as a woman are being placed up and centre and at CLOT Magazine, we are keen to celebrate it.

But pregnancy is just one of the stories hidden in The Flower & The Vessel. This delicate opus has further gifts to bestow. Many times presented as pairs of opposites; the combination of presence and absence through words, silence and space, the homely routines of floral arrangements and watching old French films adjacent to the nuisances of travelling for touring and recording while enceinte. Passages imbued in familiar light opposed to curtains that obscure rain, the intimacy of family bonds presented in the calm Fender Rhodes against the detachment of crudely manufactured synth sounds.

Félicia’s music is demanding. It bids us for a deep listening; the artist achieves this through hissed words which she uses to create profoundness, tension and intimacy by applying sparse synthetic basses that punctuate old Wurlitzer electric pianos and mellow Rhodes organs that flow around electronic swirls and Felicia’s spoken passages, phrases and words.

Félicia’s influences and inspiration come from many places, from pioneering Jazz musicians to avant-garde Metal totems, from Danish Second World War heroines and pioneering musicians to the closest persons in her life. All of this is conjured in this record which will be, for many, a defining one at the end of the year. Us, we can’t wait to see her performing in Unsound 2019.

You have a new album titled The Flower & The Vessel, which was released on the 5th of July on your label Shelter Press. This is an unavoidable question: How was the recording process?

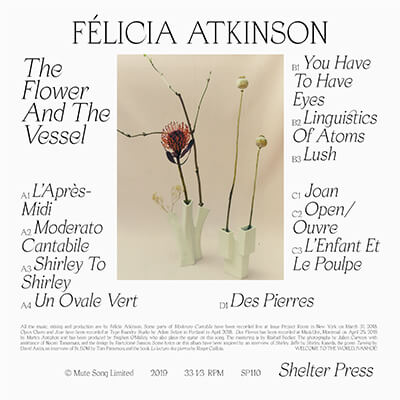

Before recording, I had in my mind this image of the cover of an Ikebana book Bartolomé bought. It was a bit of my talisman, I carried this book with me, and I would look at it as a kind of visual score. Those beautiful flowers in that ceramic with a colourful monochrome background.

I was thinking of the photograph of a bouquet that has been tarnished for a long time as a metaphor for what a music recording could be, trying to capture a moment that will vanish but also will stay forever because of the record. I was in this special state also of being pregnant, and I felt I was myself experiencing a strange notion of time, the one we call « expecting ». also had in my mind this song India Song from the eponym film by Marguerite Duras. I loved the mood in it. It was at the same time tropical and oceanic. And I wondered, in general, what is to prepare something, to be in sustain.

What time is in a record, patience in a record, but also what is an act of creativity in general, whereas it is to make a bouquet, a record or a baby, this conscious of adding something to the world, the responsibility of it but also the beauty and the fragility of it?

I recorded in two studios: Type Foundry in Portland, where I recorded gongs, Wurlitzer, Fender Rhodes, voice and vibraphone and at Music Unit in Montreuil in France, where I recorded the track Des Pierres with Stephen O’Malley, also using Fender Rhodes and Wurlitzer, but also a Jupiter keyboard and the voice with a Neumann. The rest was recorded in hotels and air and b while travelling and at home on my bed.

Half of the record was recorded standing and half laying on the bed. I read somewhere I would have felt alone because I was in a hotel, but I never felt lonely or gloomy. I was carrying my child in my belly, and my partner was also travelling with me, so I felt particularly well surrounded actually. I was also very much inspired by what I could see from my window while recording in those rooms, mostly the pacific northwest and it’s rainy and foggy landscapes that I love, the wonderful smell of pines, and the seagulls passing through the sky at home in Rennes, the promise of an ocean not too far.

In general, I think of music as a space, an environment that I organised and disorganised, but this time I also wanted to question my relationship to time and the one I would share with the listener.

Words play an important role in your compositions. Where do you find them? How do you incorporate them into the music?

I kind of fish a part of them in art magazines, handbooks and guides, but also in archives in libraries, and I do improvised cut-ups, picking the words as I am recording, playing with my subconscious. I feel very inspired by the automatic writing techniques of the surrealists and their cadavre exquis. I enjoy mixing diverse sources; my own poetry, a handbook about ikebana, a few words by David Antin or Roger Caillois, an interview of a painter like Shirley Jaffe or this strange Architect St EOM.

It is a bit like transforming yourself through those different stories, but also composing with the elements enough so it becomes abstract in a way, a bit like cubism in painting. When I play live, I also improvise lyrics, responding to so acousmatic recordings. I play live the recording as staging a kind of doppelganger.

I am very much interested in different layers of presence, whereas it is by quoting other artists and, in a kind of way, answering to them, as I am also answering to myself. I am interested in the myth of Echo versus the myth of Narcissus and also the strange oracles of the Pythies. I enjoy the idea that we all have several voices inside us speaking.

So perhaps a summary is: I relate to scenography as an ecosystem, where various actants influence and shape each other, from which aesthetics and narratives arise. I am a part of this as a scenographer, whoever I am collaborating with (human/non-human), the audience, the various machines connected to us or the space, the space itself, and then involvement by the myriad of others that I didn’t anticipate would enter that still influence the work in various ways. The work has to remain porous and open to intervention.

Also, Silence, the absence of audible ambient sound, is an important element in this record. What are your motivations for leaving more space for silence?

For me, silence connects us to space, it’s a way to make space in a composition, but it also connects the composer to alterity. Silence brings you the ability to listen and breathe. And also brings a kind of sustains that allows room for desire. Things are missing, and therefore things can happen.

Again, the metaphor of ikebana is important to me there. By removing or choosing a few elements instead of a crowd of them, you let the space shape what you do, and by opening the space, you connect yourself to the whole world. This is why one track is called Open/oeuvre. This desire to make music is not only to express something but to open yourself to the world and the listening and try to find a shared space there with the listener.

You have recorded a song in the new album with Stephen O’Malley. Could you tell us more about collaborating with such a legendary figure?

I really admire his work, and we publish a record of him, Eternelle Idole, the soundtrack of Giselle Vienne’s piece a few years ago with Shelter Press. We have a lot of friends in common and became to be friends. He contacted me to take part in his former radio show on red bull radio, which was a great show and sadly ended.

We spent a day in the studio in Montreuil, and he just bought the book The Writing of Stones by Roger Caillois, which is one of my favourite books ever, so we had from the start great serendipity between us. We improvised the tracks by layers and produced and mixed them in a day. It was like going on a boat, it was great and efficient, and I am very thankful for his invitation. I liked the track so much I decided to add it to my new album, but I like the idea that it was a radio piece first because I love radio so much.

Your new album brings classical influences of artists like Eric Satie. Recently Satie Sonneries, an obscure record from Spanish avant-garde pianist Patricia Escudero, has been repressed. I’m curious if you have found inspiration for her album. Can you tell us about other women that have inspired you?

I don’t know her work, but I will look into it for sure. I enjoyed very much listening to Els Marie Pade and Mary Jane Leech lately for the more abstract side and to Dorothy Ashby and Mary Lou Williams for the more melodic side.

Shelter Press is the platform Bartolomé Sanson, and you have created to publish music, books, and writings. On the Shelter Press website, there is a statement: the label does not accept demos. How do artists become part of the label? Do you commission specific works for artists that you find interesting?

Shelter Press is a bit like our house, and like most people, we prefer to invite people for dinner rather than accepting whoever is knocking at the door, not by fear of the unknown but more because we believe in relationships and we already have desires, projects and ideas in our mind.

Making a record is a very slow and expensive process in terms of time, commitment and money, and we tend to build, as I said, a relationship with the people we decide to work with. Also, I encourage people sending their demos to make their own labels. it’s a way to prove commitment to your own music, to decide to push it and defend it, even if it’s a big risk in many ways.

You’ve been described as an ASMR auteur. Would you like to explain to us what ASMR is and how it works in the context of your music?

I learned about ASMR by reading a review about my record, A readymade ceremony. I never heard about it before. In my case, this is not what I am reaching, the ASMR effect. I am interested in whispers as a way to use proximity and intimacy. a recording, and therefore to make perspective in my recordings. I panel a lot of sounds also. I enjoy composing as I draw, some elements are close, and some are far.

I used different layers of voice. Sometimes once you can only hear in the headphones, a bit like in a pointillistic painting. But a voice is only a part of it. I started whispering in my recordings because I was recording in my bedroom, and I didn’t want my neighbours to hear me, and I didn’t want to record the sound of the street around me, so I would go close to my phone for those two reasons. In the beginning, it was driven by casual reasons.

I find a strong connection between the readymade art movement and your music. Is readymade a concept you translate into music?

In some ways, yes. This is why I called one of my albums A Ready Made Ceremony. But for the latest one, The Flower and The Vessel, I was more inspired by ikebana. But both are ways to compose something simple and at the same time, poetic in the chaos of the world. it’s a gesture, a way of leaving and of thinking.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I believe in democracy, equal rights, freedom of speech and travel and the fight of global warming. The people against that are the chief enemies of creativity

You couldn’t live without…

Water, air, light and love, like any creature.