Interview by Jack Apollo George

If I lose the signal on my phone, how will I know where I am? If I can’t see something microscopic, how can I know that it is there? A direct understanding of our present condition is made impossible by the pace of technological change. It is unrealistic to keep up with every new scientific innovation, with every single shiny new product. If we stare directly into the light, we might feel a sense of vertigo—nausea instead of wisdom.

Frederik De Wilde does not question innovation directly. He knows that would be a misuse of his conceptual nous. Instead, it is around the edges of our known universe that he probes. His mind undoes and then reveals the limits, the interstitial, the unseen. From making a mould out of the quantum vacuum, to jamming Wi-Fi signals around some of his sculptures, he is a master of the spaces in between. As he puts it—the conceptual crux of his praxis are the notions of the inaudible, intangible and invisible. De Wilde looks at the spaces left unexplored by art and science as well as the overlaps between complex systems. He is not limited to any one perspective, with societal, biological and technological considerations all coming into play.

Born in 1975 and a graduate of the universities of Sint-Lukas and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Belgium, Frederik De Wilde’s art has been exhibited for over 20 years. A skilled sculptor, dancer, painter and curator, his work is not confined to any one medium or ethos. Instead, using his broad range of influences, De Wilde crafts conceptually ambitious pieces which test the very boundaries of our experience, both lived and imagined.

He is no stranger to technology and relishes the manifold opportunities offered by our contemporary age. A telling remark in the interview is his assertion that we don’t mine anymore in this regime, we edit and grow, and in his embracing of nanotechnology and 3D printing, we see an artist who never creates in a conceptual vacuum but rather reconfigures existing entities in order to shine new light upon them.

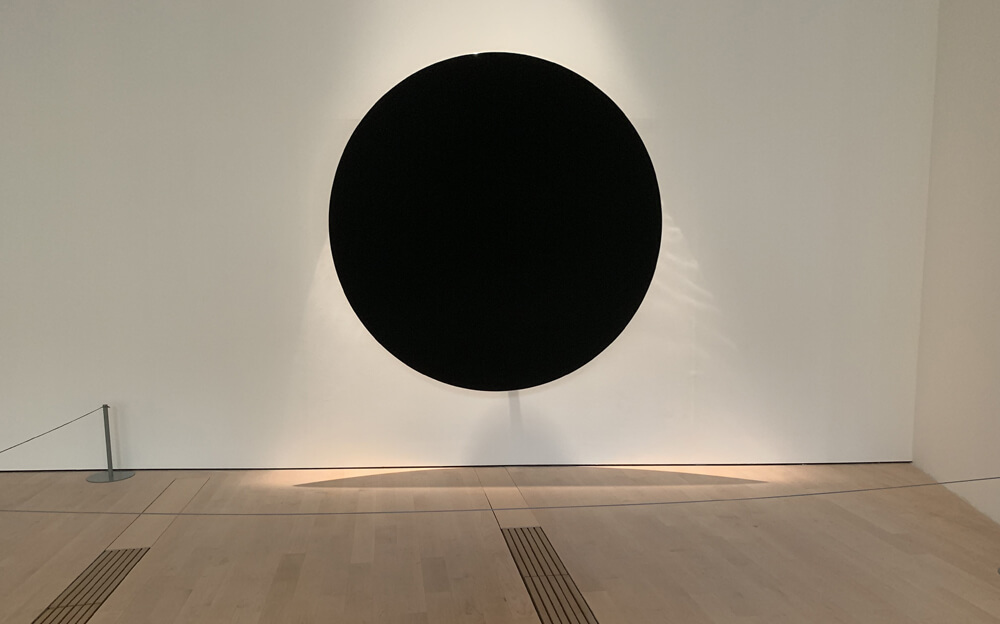

In collaboration with NASA, he famously developed the Blackest-black art, a ‘colour’ created out of carbon nanotubes—and 99.9% air—which absorbs light to such a degree that 3D objects can appear as two-dimensional planes. It is too dark to make sense of. The detail involved in crafting the colour makes it as important a scientific innovation as an aesthetic one. The Blackest-black art was used for paintings and 3d printed sculptures and was conceived of and developed years before Sir Anish Kapoor bought the rights to his own, controversial Vantablack.

Frederik De Wilde delivered a TED talk on the Blackest-black art and is working with Carnegie Mellon University, NASA, Astrobotic and Space X to take the art to the moon.

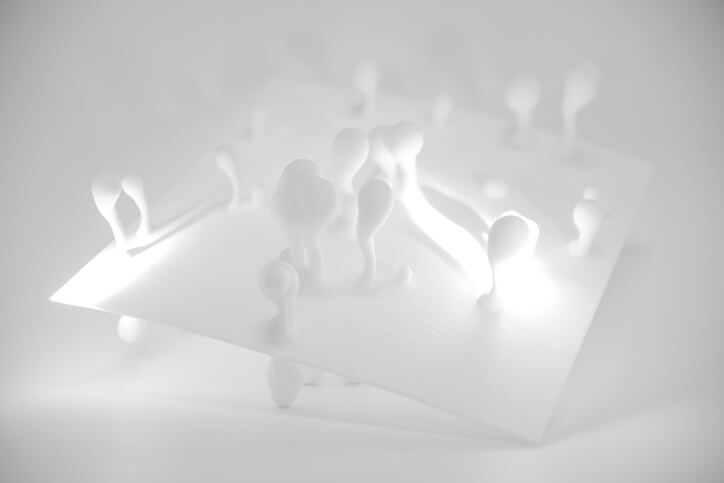

Right: Quantum Objects #1 [plane], Studio Frederik De Wilde

You are interested in the blind spots between art and science. How do you transcend or reinforce that conceptual obscurity?

I tend to gravitate towards the ‘dark map’ or un/under-explored crossovers between art and science, by extension, technology. I’ve always seen many parallels and kinship between art and science, yet there are also very distinct differences which make them also complementary. Both art and science require creativity and imagination to question assumptions that everybody else has bought into. That is the hardest but also the most exciting part. In my daily crossover praxis, is tend to blur the distinction. It becomes fuzzy or, as you call it, obscure.

I think that in this liminal space or interstitial territory, the most exciting things can occur. This is, of course, not limited to disciplines, methodologies, media or materialities; it dwells and stretches out to psychology, phenomenology, the possibility of metamorphosis and phantasmagories, after images and trace effects.

For instance, my pioneering blackest-black art series situates itself in a particularly interesting crossroads: between the ‘dematerialization’ of the art object’ that heralded the conceptualism of the 60s and 70s arte povera, conceptual art (e.g. J-F Lyotard’s exhibition Les Immateriaux at the Centre Pompidou, Jacques Derrida’s exhibition Memoires d’aveugle at the Louvre) and of course minimal art. The blackest-black artworks push this legacy to a new extreme—and you can take that literally—due to recent advances in nanotechnology.

‘Criss-crossing’ these histories and developments is what makes me curious and my ‘clock’ tick. Here’s an interesting quote that ties it all together: At best, we can describe our efforts in understanding the origin of our universe as probing around the “edges” of our understanding in order to define what we don’t understand, much like a blind person would explore the edge of a deep hole, learning its diameter without knowing its depth. [Schombert, 2013a].

‘The intangible’ is one of the core notions of your praxis. Can you describe how you go about trying to craft and construct the intangible?

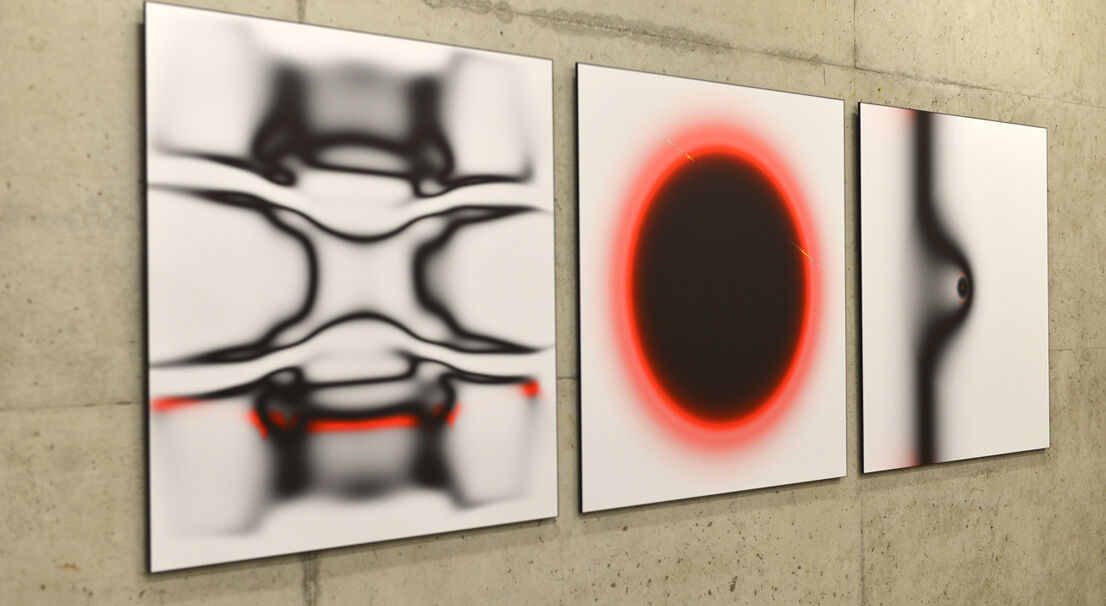

There’s no one way or strategy really and would make the process less exciting anyway. In my Quantum series, I collaborated with top scientists from the National University in Australia in the Quantum teleportation, encryption and communication lab. By setting up an innovative tabletop experiment with entangled photons, they were able to tap and listen to the quantum vacuum and, more specifically, quantum fluctuations or noise.

These real-time measurements were then used as raw data transferred over the internet to generate pretty complex shapes in a 3D environment from custom-made software. These extremely short-lived virtual particle pairs of matter and anti-matter destroy each other in a very, very short brief moment, and that’s why we call them ‘virtual’ by the way. We can, in fact, only measure them by the force they exert on particles we can more easily measure.

I translated the digital 3d model via 3d printing into something palpable, made a mould and poured it into concrete. I think that is very poetic, no? Turning the most ephemeral, fleeting and invisible in the Universe into concrete! I could even argue is the most ancient artefact ever found and made.

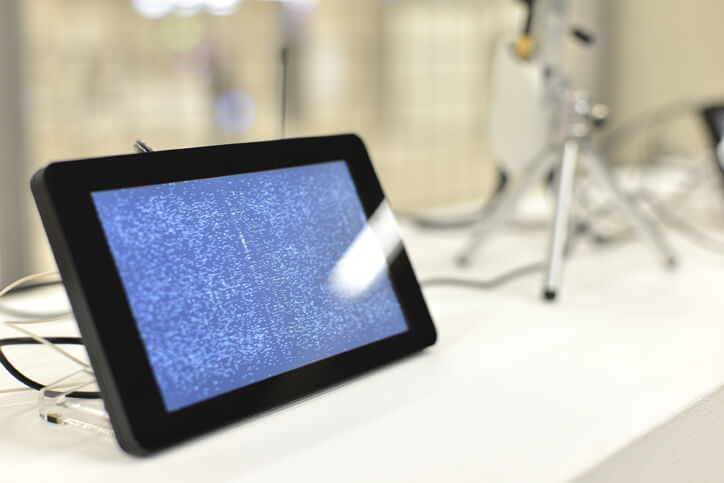

Another artwork is “HyperThinker #1/#2 – TheRight2Silence”, the #1 being produced in the framework of RESONANCE II powered by the JRC EU. The artworks render us network-less and unreachable while challenging us to reflect upon our relationship with digital networks (e.g. what to block and what not, ‘quiet’ zones, the right to silence, the ‘grey’ legal zones, …), machines, algorithms, contemporary rituals and ultimately ourselves.

There’s a strong reference to Rodin’s famous Thinker sculpture. Thinking is generally conceived as a solipsistic activity that we do on our own. Yet, as contemporary thinkers, we are also plural and relational in our online and offline lives. With the artworks, HyperThinker #1/#2 – TheRight2Silence, I want to expose our hyperconnectivity through the subversive act of jamming GPS and wifi networks in the vicinity of the artwork, hence critically questioning the nature of the radical shifts that hyper-connectivity imposes on the human condition.

Once manifested, how do you ensure your work remains intangible?

It’s often through illusion or simulation, and being able to suspend it in time, that one can experience something that is, feels, more real and profound than something tangible. My latest blackest-black artwork is exhibited in the landmark MINIMALISM space. object. light exhibition is such a visual ‘intangible’ enigma.

One could argue it’s a border guard of matter, a thin membrane between the spiritual and material worlds, a portal, really. Only a paradox can create enough ‘gravity’ (e.g. like a black hole) that we naturally gravitate towards it out of curiosity, awe and fear, … the unknown. My blackest-black art is such a paradox in a plethora of ways, for instance, the fact that I have to add the most minimum amount of material to see nothing(ness). That bare minimum amount is 0,1% carbon and 99,9% air. That’s pretty crazy.

A couple of years ago, you took part in a NASA collaboration to produce the Blackest-Black art. Not long after, Anish Kapoor purchased the rights to his own hyper-dark Vantablack. Why do you think artists are racing towards the invisible?

Let’s take a few steps back. I started my research in 2008 by pondering a seemingly simple question “Is there something blacker than black?” I did my homework and went to Rice University to work with a pioneer and world authority in nanotechnology Prof. Pulickel to work as the first artist-in-residence in his lab to develop my concept. This was in early 2010 (my collaboration with NASA started later).

The results of our crossover arts-science research and development collaboration received many awards, e.g. the best European award for collaboration between an artist and scientist, an Ars Electronic Award, and laureate of the TED ideas worth spreading global talent search, …, just to illustrate, we have a long track record of events that took place way before Surrey Nanosystem’s collaboration with Sir Kapoor.

You know, the blackest-black is a beautiful mind-boggling concept of which I am really glad that it profoundly inspires people and artists like Sir Kapoor, which I am holding in high esteem, and Surrey Nanosystems to build on the legacy of the original blackest-black developed by myself and my pioneering scientific partners.

The concept of the void is a centuries-old theme crossing art, science, mathematics, literature and so on. Nothingness and emptiness as concepts is something that’s really hard to wrap your brain around really, and it’s very relevant in times of visual excesses, mass (mis)information, sensorial bombardments and so on.

What I am trying to do is to add a few layers of meaning atop the traditional viewpoints that are valuable for me and resonate with my time, e.g. privacy issues, global warming (i.e. carbon) and fossil fuels, and space travel. These topics make my blackest-black artworks extremely relevant and (post-)contemporary. It’s a new colour for a new industrial revolution. We don’t mine anymore in this regime. We edit and grow. That is exactly what I’ve done in the lab.

What new technologies or scientific discoveries will further enable this pursuit?

Space and military-related research, undoubtedly.

In the past, you have said that “human, social and ecological problems are often the starting point of my research.” What issues can we expect you to tackle next?

(Re)connecting people and the world around us in a hyperconnected era; fighting global warming with colour; a critical lens on privacy through obscurity; learning to enjoy with less material, less energy consumption and more efficiency; stimulating critical thinking, curiosity and imagination; finding an exit(s) for mankind.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Definitely not boredom, hmm… bad food and shitty politics.

You couldn’t live without…

Imagination, passion, love, curiosity, water and grandma’s infamous rice pudding.