Interview Laura Netz

Artist Haroon Mirza’s interest includes physics, shamanism, artificial intelligence and astrology. There are many things in between, such as music and sound theory, art and aesthetics, particle physics, cosmology, ethics and moral philosophy, shamanism, and so on.

Indeed, Haroon Mirza’s preoccupation with sound waves comes from his experience at Winchester School of Art in Southampton when the artist first started working with acoustic space. In particular, the experience at the Institute of Sound and Vibration Research (ISVR) and its anechoic chamber was decisive to understand and experience waves and to comprehend how they are perceived, the responses they create and the various ways in which humans relate to them.

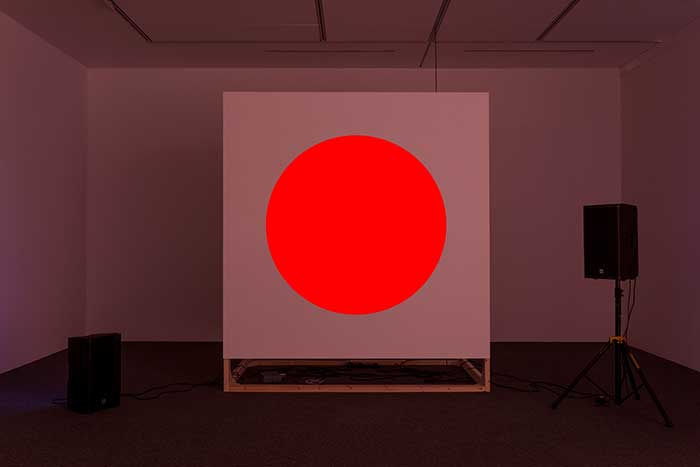

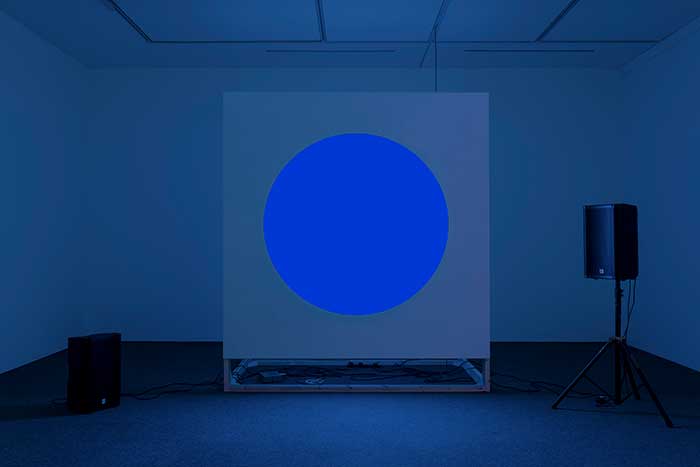

I use electricity as a medium (which can be rationalised as waves), and waveforms are an inherent subject in my work, which in simple terms is reality – or, more particularly, our conscious relationship to existence, Mirza continues. One of his latest exhibitions highlighting this relationship is Waves and Forms at John Hansard Gallery in Southampton, an experiential exhibition about Mirza’s ongoing exploration of waveforms across light, sound, electricity and water, and the emotional and physical responses they create. It’s a multi-sensory experience that combines art, science and design through immersive installations.

The exhibition displays digital animations, videos, audio, LEDs, multichannel sound installations, sculptures, and a sound chamber. The works exhibited include Skip_loop (2019) shows a digital animation of the sea which collapses in six-second intervals; /\/\/\ /\/\/\ (2017) —read as “Aquarius”— is a multimedia, multichannel installation and sound chamber in which the viewer experiences sound and videos.

Solar Symphony Solar_Corb B/ Solar Symphony Solar_Corb D (2014) are sculptures made of natural light exposed to solar panels illuminated by LED and bicycle lights connected to speakers to amplify the sound of the electricity; and finally, Pavilion for Optimisation (2013), is a sound chamber designed to experience reverberation as a continuous prolongation of a sound.

Another highlight of the exhibition is Dreamachine 2.0, a system to induce dreamlike states, developed in homage to the prototype created by Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs. With the collaboration of artist Siobhan Coen, both reimagined the historical stroboscopic lamp using microcontroller-driven LEDs.

Waves and Forms is on view until January 11, 2020, at John Hansard Gallery in Southampton.

You seem to have a plastic approach to sound: you are an acoustic manipulator, a sculptor of sound; some of your works seem to be organised according to architectural principles and not exclusively artistic because you use extremely heterogeneous acoustic sources and then expand the sound by following the characteristics of the space you use. What is your favourite sound perspective? How do you direct the creative process of your sound works?

These days I like to experiment with the physiological effect of sound, particularly psychoacoustic and neurological effects that may be linked to transcendental, mystical and visionary experiences. This is often combined with spatialising sound within a particular architecture to enhance these effects. These scenarios can then be handed over to scientists to study what may or may not be actually going on. This way of working is relatively recent and has evolved from a more phenomenological and acousmatic relationship to sound.

You define yourself as a composer rather than an artist. For you, what are the main differences between the two terms?

An artist is a broad term that encompasses many things – someone doing makeup is also an artist. I find “composition” a more precise term for someone that arranges visual material in space and acoustic material in time simultaneously.

As a composer, you have a strong academic background. Are there any theoretical or critical references that have influenced your practice?

There are many influences ranging from McLuhan and his ideas around technology and acoustic space to Rick Strassman and his study of DMT on human subjects. There are many things in between, such as music and sound theory, art and aesthetics, particle physics, cosmology, ethics and moral philosophy, shamanism, and so on. I’m curious about a lot of things, and most of these things influence my work.

Your work has distinguished itself internationally for having a particular interaction between waveforms and electricity. How do you use these elements in the installation field?

My main medium is electricity, which I manipulate either through analogue means or through digital programming, often to create compositions of light and sound. Both light and electricity are part of the electromagnetic spectrum, which we understand or rather rationalise in waveforms. In fact, all of reality can be defined as what physicists call a wave function and as conscious beings, we “collapse” the wavefunction just by observing the reality.

So in answering your question, I use electricity as a medium (which can be rationalised as waves), and waveforms are an inherent subject in my work, which in simple terms, is reality – or, more particularly, our conscious relationship to existence.

Sound is certainly one of the most powerful tools to stimulate the sensory and emotional participation of the audience. Could you explain, from a technical point of view, how you worked to create such immersive works like Dreamachine 2.0?

It comes from many different points of inspiration, research and collaboration. There is obviously Ian Sommerville, Brion Gysin and William S Burroughs’ device that creates flickering light. We were also thinking about the practice of what’s known as shamanic drumming: a constant drumbeat of around 3Hz – 6Hz, which induces trance-like states probably due to stimulating theta neural oscillations in the brain.

Then lots of advice from neuroscientists and programmers helped developed the piece. It initially began with Siobhan Coen doing a residency in the studio. She developed the dome with flickering light. I then introduced the acoustic element and shamanic/neurological references.

In terms of research and artistic experimentation, how important was it for you to work in an anechoic chamber? Has your perception of sound changed?

Hugely important. The entire show at John Hansard Gallery has come from spending time in both an anechoic chamber and reverberation chamber between 2000-2001 at the ISVR in Southampton. I think the influence is evident.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Can’t think of any.

You couldn’t live without…

The people I care about in my life.