Text by CLOT Magazine

More than half of all data stored in clouds is no longer in use. In impenetrable quantities, data loses meaning and can be described as garbage that consumes energy and other resources. But what if we could upcycle this unused mass of data? The exhibition Passing Data — Upcycling the Digital is an experimental approach to data waste; six artists were invited to test upcycling as a speculative method for re-utilising old data. Veneta Androva, Raphaël Bastide, Bruno Gola, Kathrin Hunze, Yehwan Song and Shinji Toya searched for data they no longer needed on their computers, cloud servers, or hard drives. In tandem, the two artists swapped images, fonts, videos, sounds, or code and incorporated them into their artistic practice. They embedded the files in ongoing projects, made room for them, or used them to inspire new ideas.

Passing Data – Upcycling the Digital is an online exhibition at Prater Digital – an independent section of the communal Prater Galerie since 2020. It is embedded in the annual program COPY PASTE WASTE, which explores digital sustainability from different perspectives. In the following conversation, the curators Katharina von Hagenow and Tereza Havlíková reflect on the process of upcycling as a speculative sustainable digital practice and look together at the artworks in the exhibition.

Katharina von Hagenow: The idea for this project came two years ago when we considered a sustainable curatorial practice at Prater Digital. Observing the massive amount of files and data we produce as we set up online exhibitions or events- the text files, the different versions of graphics, the back-and-forth e-mail communication, etc.— We wanted to create a programme on digital sustainability that would raise awareness in a playful and inspiring, rather than in a moralising way to reflect on the issue of data waste and its impact on climate.

Alongside the first parts of the year-long programme COPY PASTE WASTE, experts gave us impulses to sketch a complex relationship between digital infrastructure and sustainability. In the meantime, we initiated a network with other cultural institutions focusing on digital art practices. In regular online meetings, we debated where action was needed and where the institutional side could change their work patterns to aim for more sustainable digital production. With the Art Swaps and the online exhibition, we wanted to explore an artistic approach to the matter.

Tereza Havlíková: In our Art Swaps, the brief was not to make a work about (digital) sustainability, although, in the end, many works address it as a topic. The focus was on upcycling as a curatorial and artistic methodology. Upcycling creates a new life cycle for a redundant item; it is a well-known technique for handling physical resources. Upcycling gives the item a new purpose than it was initially intended for. With Art Swaps, we wanted to test whether it could also upcycle digital resources. But we don’t mean electronic waste, like old devices (although that would also be an important task), but we suggest the files and data we produce daily.

We knew others had done this kind of data recycling or upcycling before us. For example, the Berlin-based artists Joachim Blank and Karl Heinz Jeron created Dump Your Trash or Mark Napier’s Shredder 1.0. The idea of taking old data and creating something new was quite popular in the 1990s. But we took the idea and put it in a context different from the internet era.

Through the exercise, we also asked if it is possible to upcycle old data without producing new ones. Or what do we do with old data when there’s seemingly no reason to delete it? So, we were setting new limits and challenges for the artists and ourselves to trust the process and lose control over the result. Not everyone is willing to embark on such an adventure, which is entirely understandable.

Tereza Havlíková: To choose the participants, I thought about artists whose work I like (of course) but also whose view on technology and its role in our society I respect. It was vital that they work with digital tools and might understand the computer better than we do. I tried to find artists I felt would be open to this experimental exercise and collaboration.

Katharina von Hagenow: I was so impressed that all artists took this challenge on and embraced upcycling as part of their creative process rather than just executing an exercise. And it was interesting to see how differently they approached it—for example, Kathrin Hunze and Veneta Androva, who both contributed video works to the exhibition. Beyond the donated files, they introduced the topic of digital sustainability into their work.

Veneta began with in-depth research into the sustainability of data centres and became very interested in the phenomenon of the so-called ‘zombie servers’. Up to 30 % of all servers in data centres operate as zombie servers, meaning they only stand by idle as a backup, yet their energy consumption is significant. In the resulting video work HOTSPOT, Veneta skilfully uses her research to bring us to the hidden world of data centres. Apart from the ecological impact of data centres, she explored these technological places’ social and cultural environments. She used the abstract video material from Kathrin Hunze as a canvas on which she projects her narrative.

On the other hand, Kathrin Hunze added the GIF file she received from Veneta to her enormous 3D file archive. This immersive world formed the basis for her video essay WellNet: Help Yourself, which discusses digital commons and the data economy. In it, she imagines a network where users own and are responsible for their data.

Tereza Havlíková: It’s no surprise that artists working on and with the Internet are very sensitive to its power dynamics, and this structural and political critique needed to become part of the exhibition. Kathrin addressed how the commercial logic of the internet forces users to produce as much data as possible, thereby increasing its ecological impact. And I appreciate that she chose an uplifting, inspiring and, frankly, hilarious story as a method of critique rather than a depressing dystopian vision. Kathrin created quite a unique aesthetic of the 3D space, rich in layers and textures. She is moving from analogue black and white noise, through RGB-coloured old-school internet aesthetics, to this sort of contemporary fluid and shiny appearance of virtual worlds.

Katharina von Hagenow: Yes, now you are referring to her second video, Xanadu: wellNet project, which is this wild world including all the data and files she has ever created. This work highlights the data overflow, which is precisely our project’s starting point. In reflecting on the more extensive system of the internet, her work also relates to Raphaël Bastide’s contribution. He intended to create a “cosy space”, a website, on his server apart from the mainstream commercial internet places. He spoke about creating a nest for the audio file Bruno Gola gave him.

Tereza Havlíková: At the same time, Raphaël refused to use another file from the swap because it would have required an additional program, which he didn’t want to install. And that made us think about what we need to install and how often we are forced to install new things. Once he decided to focus on the recording, the file became this critical thing you care about. So, I feel that in Raphaël’s work, being mindful towards data comes through. I can sense it from the work, from its joyful, colourful and playful aesthetics. It is cos,y and it is soft.

Katharina von Hagenow: Yes, and I have to think about the Studio Visit with Raphaël, where he invited us to visit his computer and showed us his desktop and digital work routines. He has this very mindful approach to the computer as his space. He invests a lot of time rebuilding the technology so it works how he wants, making it his home. It’s inspiring because most of us don’t even consider the default settings. This demonstrated his enthusiasm for free software and his web-based practice, which aims to improve the internet.

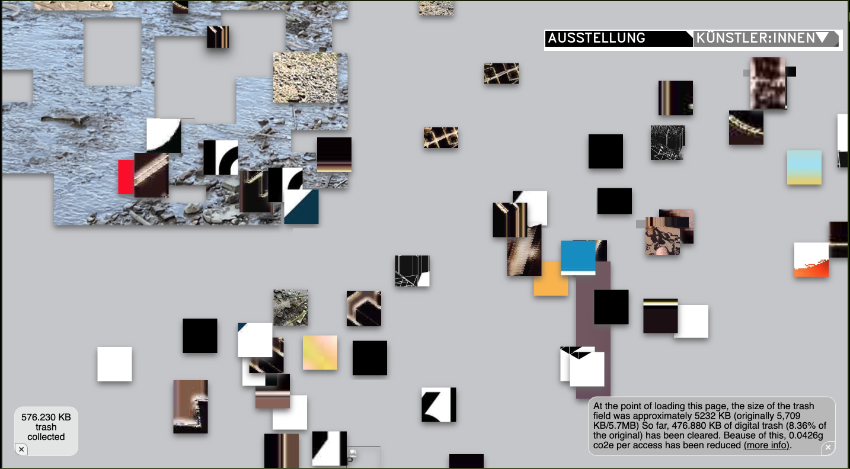

Speaking of web-based artworks, there is also the website traschpicking.cloud by Shinji Toya. He has been interested in digital sustainability for some time now and has done projects on data decay, e-waste and the notion of forgetting on the internet. For the exhibition, he created a wasteland website where people can delete various images and graphics he got from his Swap partner Yehwan Song and some of his unused files. By deleting, the visitors can see how many kilobytes and therefore CO2 emission they reduce. The task of deleting and cleaning up becomes a meditative, satisfying work.

Tereza Havlíková: I think it’s also possible to read Shinji’s work in relation to Kathrin’s work because he also created one space for many files. However, in his work, the files are superfluous; they are trash-holding data and consume energy on the server. It makes me think about who is responsible for trash in public spaces (on the internet or in the park on the riverside). It reacts to a collective blindness towards trash in general. For me, this work is more about tidying up and cleaning up than Kathrin, who is trying to archive everything for the potential of future creation. So I think these two works show two sides of upcycling – do I need it? No, okay, so I can delete it. Or do I see chances in the data to be used in the future? And this decision often feels overwhelming because we are scared to delete anything.

Katharina von Hagenow: But I think Shinji, in his previous work, also talked about decay or decomposition in a way that nothing gets lost, but it changes, mutates, becomes anew – like physical material. Perhaps it is interesting at this point to talk about the work of Bruno Gola, whose essay also refers to decay as a form of transformation. Raphaël added a letter to tell a story about the donated file – a font he created some time ago. Bruno not only responded to the text by continuing it but also manipulated the font file itself so that the text appearance was constantly transformed for the duration of the exhibition. The font is less readable than at the beginning and continues to be further and further abstract.

Tereza Havlíková: Because Bruno has a background in computer science, he has an excellent understanding of digital objects and code. He made us think about what digital ‘material’ is in the first place and that it’s a code that needs to be read to be executed. Even something as simple as a font is a small script with many parameters that define the font’s shape and behaviour. He made us think about how all digital objects should be seen as processes and how they must be run, used, and executed. Otherwise, they disappear pretty quickly. I read decay here, much more like uncontrolled disappearances, the loss of digital goods because, at some point, we won’t be able to use them anymore.

Katharina von Hagenow: Even if we don’t have the hardware to execute the file, it still exists as a language – it’s just a language we no longer understand. So, the work could also be understood as a comment on human versus machine languages and how they translate and interact. There is always a code behind an interface.

Tereza Havlíková: Speaking of interfaces, there is another link: Yehwan Song’s work also deals with that topic. In her video performance, she decided not to use the actual data Shinji gave her but rather to use it as an idea for reflection.

Katharina von Hagenow: Yes. Yehwan received a different file type from Shinji, and she got photos showing Shinji’s broken keyboard. Unlike the other artists, Shinji did not select files from his previous work but images that are typical of our everyday ‘junk’ data instead. We have become used to documenting everything with our mobile phones and rarely delete photos that function as ‘notes’ and memory aids. Even though Yehwan didn’t use Shinji’s pictures directly, they inspired her to explore the keyboard as an interface, a membrane between our bodies and the computer. In our meetings, she reflected on how computer interfaces increasingly become invisible, immersive, and close to our bodies, almost like body extensions.

Tereza Havlíková: It’s fun that she created nail extensions that exhibition visitors can download and 3D print at home. To round this up, let’s briefly talk about the design and structure of the online exhibition. Even though there is quite a history of exhibition-making on the internet in the context of a communal gallery, this format is also unusual for the audience. So, I think we were trying to pick up on this history of curating on the internet and move it in a new direction.

Designed by Karolina Pietrzyk and Tobias Wenig, the exhibition is based on the ASCII graphics that have defined the look of the entire annual programme. This older graphic method, popular when the Internet was still without images, was deliberately used to save data.

Katharina von Hagenow: It was also a question of how we could save data without sacrificing the quality of the artwork. We did not want to put any restrictions or limitations on the artworks, but we tried to be concise with all the other elements we built around them. So we have the fly on the project website, which gives you more information about the website and the connection between the internet and C02 emissions, and the website also shares how many KB it loaded with each visit.

Tereza Havlíková: The central point of the exhibition – can be read as a mind map or associative diagram. It reflects on the data overload, but we also wanted to show the artworks clearly defined on their own. Every work has its page, so visitors realise the border of the individual artworks but still get a sense of the exhibition as a whole and collective effort with its different layers and interconnections. We warmly invite everyone to browse the exhibition, get lost, find their way around the map and be inspired by the artworks.

The exhibition is on view until the 28th of February 2025 at Prater Digital*.