Interview by Christopher Michael

The 21st century’s first two and a half decades have primarily been defined by a conflation of corporate, public, and private environments. In major cities like New York, supposedly ‘public’ common space increasingly exists only due to tenuous agreements between public and private financing, leading to the rise of POPS (‘Privately Owned Public Spaces’). Even the internet, which once promised an egalitarian digital commons to its users, has become a playground for corporate power — mainly to the disadvantage of the general public.

Jason Isolini is a multidisciplinary artist interested in exploring these conflations of space. Before realising he was a visual artist, Isolini was enamoured with skateboarding — an activity that inherently tasks its participants to blur the lines between public and private space. Isolini’s visual art practice is similar to skateboarding, where artistic action becomes an intervention with the space.

In works such as The Ballad of a Laborer and Public Core, where he uses Google Street View as a medium, his interventions ask how we might define ‘virtual public space’ concepts. Elsewhere, like his 2022 exhibition Out of Office at the Public Works Administration, his critical interventions highlight the narrowing gaps between one’s ‘professional occupation’ and artmaking practice, another space in which private and public lives have become increasingly entangled.

In his most recent solo exhibition, You’re Bringing Me Down, at New York’s Picture Theory Gallery, Isolini continues exploring themes of conflated spaces, this time posing questions regarding the labour inherent in keeping our digital infrastructures running. The exhibition’s title refers to the directional scrolling of most social media and the digging of the large-scale mining required to maintain the infrastructures on which the internet is built.

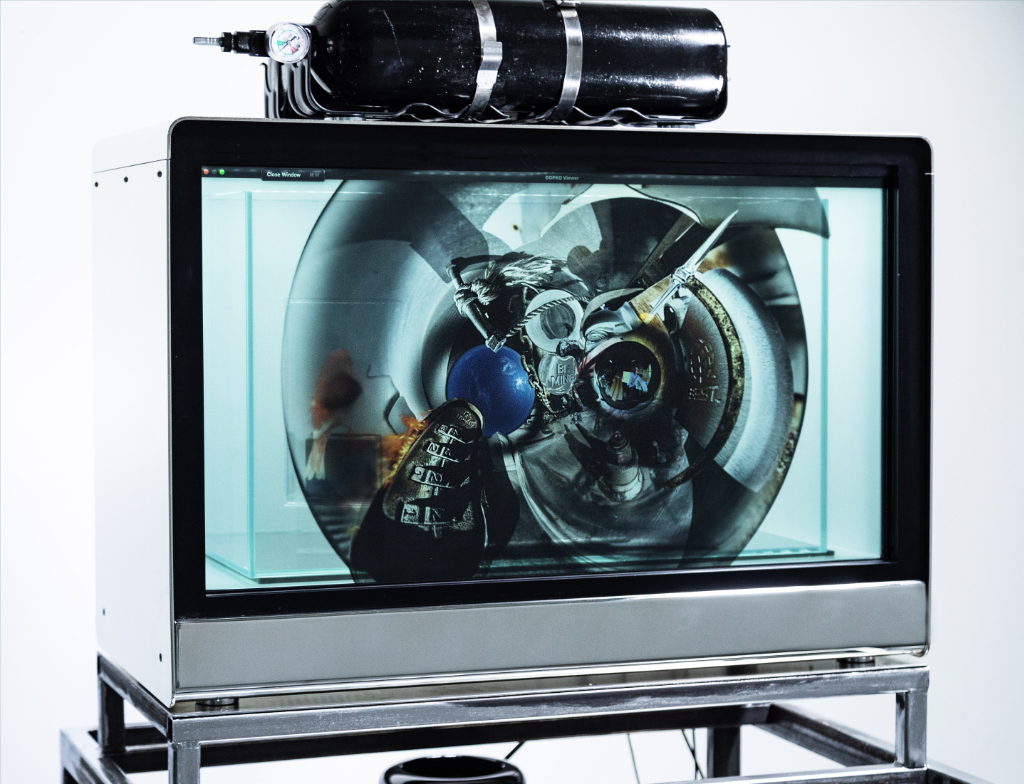

In works like Fish Tank Website, an interactable new media sculpture that combines personal computing hardware with an active aquarium of live fish, Isolini makes explicit the links between browsing the internet and the extractive means required to keep it powered — the aquarium pointing toward practices of sea mining for polymetallic nodules. In doing so, the immersive sculpture alludes to new energy paradigms established in our historical moment, making these power relations transparent to the viewers.

A recurrent theme of the exhibition is the idea of ‘the canary in the coal mine’, an idiom that references 9th- and 20th-century uses of canaries in coal mines to detect toxic gas. Thinking specifically about the booms and busts of cryptocurrency and market bubbles, Isolini felt there was resonance between the idiom and the increasingly volatile infrastructures of digital spaces. Isolini uses actual taxidermied canaries in Revival Cage (Untitled) TLCD 1-4 to bring new life to the metaphor and explore its meaning within contemporary discourse.

Rather than using a canary to warn us of impending danger, Isolini wonders if we, the users of these digital spaces, have become the canaries in the coal mine. Through these poetic juxtapositions, Isolini calls to mind the creative and destructive capabilities unique to the contemporary moment.

Your practice investigates the conflation of corporate, public and private environments. Where does your interest in these entanglements come from?

It’s a good question— it makes me think of how engulfed I was with skateboarding before realising I was a visual artist. Speaking of the skateboarding subculture, it’s all about finding “spots” or otherwise unique street obstacles that are architecturally opportunistic for a “trick” or manoeuvre. Typically, these construction designs are unintended for the sport, so action becomes an intervention in the space. This pursuit turned me into a modern-day explorer, which involved much trespassing— I quickly learned what the boundaries of private and public spaces were.

Not many people understood skateboarding as an art form in the early aughts, much like how contemporary art can weave between indiscernibility. I imagine the conceptual reinterpretation of the environments surrounding me during this time contributed to my interest in private/public subjects.

Much of your work reappropriates publicly accessible materials, like rentable scooters in Steal My Sunshine or Google Street View in The Ballad of a Laborer. What attracts you to working with such unconventional mediums?

Steal My Sunshine was a guerrilla installation performance piece prompting twenty-four artists to engage with rentable e-scooters as a surface for a group exhibition. The itinerary included renting and driving the scooters into the gallery, then having a professional installer vehicle-wrap them with custom artist graphics. To hold the rentable scooters at the location long enough, multiple artists would reserve and re-reserve the e-scooters through the online application.

It was a fantastic scene— alarms went off as the installers stretched vinyl over the scooters. The idea for the show came from wanting to subvert corporate strategy to monetise public parking spaces. Since an art gallery is arguably public, I wondered what would happen if the e-scooters got parked in an exhibition space. A few of my questions were: “Would the user who came to rent an e-scooter become an art spectator?”—”Would the gallery become a kind of fulfilment center?” Thanks to my co-organiser, Collin Clarke of Mery Gates and the incredible group of artists involved, it was a real success.

At sunset, the reimagined e-scooters were parked back on the street as rentable artworks. The show is an excellent example of my interest in user-based hacks. I love to think about the misuse of these services to create new ideas, forms and approaches that feel relevant to what art might be today. Maybe they seem like unconventional ideas to a traditional gallery model, but to me, they expose an operational syntax ripe for artist intervention. This is why artist-run spaces that fearlessly host these kinds of shows, like Mery Gates, are so important. It also helps if I feel like I’m getting away with something.

Your latest exhibition, You’re Bringing Me Down at Picture Theory, presents a wide array of your work with various media, including moving-image performance, lens-based visual opacities, and more traditional methods. How did this exhibition come about, and what are some of the themes that tie these works together?

In 2022, I spoke with a friend about the booms and busts of crypto and market bubbles when they used the idiom “the canary in the coal mine” to describe indicators of impending collapse. I got intrigued by the history and lineage of the idiom, which references 19th and 20th-century uses of canaries in coal mines to detect toxic gas. I was already working with transparent displays and substrates such as lenticulars, often called lenses.

Whether mining digital currency, coal, or human behaviour for capital gain, the various extraction interfaces became a lingering subject of interest. Recurrently, my work explores anamorphic imagery, cartography, and map projections through 360º video and panoramic photography— it’s media I feel defies one kind of visual direction. Naturally, the elasticity of this media can envelop me as a performer and lend itself to modes of sculpture. This exhibition presents a question of media direction to forms of extraction. Coal mining is an act of moving ever deeper into the earth’s surface.

Similarly, scrolling social media as an inadvertent tool of surveillance capitalism thrives on behavioural mining, which forces one’s fingers into repetitious swipes from an infinite media resource below. These vertically-scaled structures and media flows shape our economies of exchange. I like to think that seamless or immersive forms of media allude to new energy paradigms and that pushing against these aspect ratios, so to speak, is what living through our historical moment is about.

In pieces like Fish Tank Website and the series Revival Cage (Untitled) TLCD 1-4, you juxtapose ‘organic’ components, like live fish and taxidermied canaries, with ‘inorganic’ components, like LCD screens and PC hardware. What drew you to create work that brings together such disparate elements?

These pieces could be best described as new-media sculptures; this combination of elements feels natural. When reinterpreting the original canary resuscitation cages, one can already see a technological augmentation of a raw bird. Additionally, the image of a miner with a canary is a poetic juxtaposition.

I was interested in using these poetics to consider what this idiom could tell us about our current moment. In my work, the taxidermied canaries are set in chrome dioramas surrounded by an architecture of PC hardware, SIM cards, and convex mirrors. I’ve thought about the canaries as cyborgs travelling beneath a technological dystopia, which suggests that the user may be the canary in the coal mine. Because the oxygen tanks attached to these works were made for humans, there’s also an implication of a need for air in a breathless oscillation of media-as-encasement.

I wanted to take the work for the Fish Tank Website and invert it like one could distort a seamless stereographic image— I thought of the Revival Cage works flipped inside out. Through cartography and map projections, images can be distorted in a way that can change how they’re seen. For me, the fish tank presented another frontier of extraction: sea mining for polymetallic nodules. It’s also a navigable work that a click-and-drag mouse gesture can operate, so it worked best as a website. It seems like computers are already morphing into different objects, so why not experience live goldfish within the browser?

Much like your more significant practice, this exhibition asks viewers to consider where the public sphere is today. How have your ideas of public space changed through your work?

In the exhibition is a piece called “Public Core,” which documents a performance I did in the center of a Wyoming Highway bordering two major coal mines. I was interested in the center of the street because it’s where virtual public space has been defined on Google Street View. As a browser-based utility, Street View is unique because it positions the user in the center of the road, an unlikely place to experience public space physically.

Public Core is about a kind of personal retribution and simultaneity towards forms of extraction. One is an extraction of geographic data that monetises the center of the street through a photo-based virtual reality. Adjacent is a physical excavation that’s operationally opaque and ecologically destructive. A deeper consideration of what characterises these boundaries is emerging from the performance work, i.e., the space between the double yellow lines or the space within a line itself. Much interest has been in thinking about space as a continuous drawing and an ongoing act of mark-making.

What is more important: knowing or not knowing what you’re doing?

Over the years, I’ve learned how I work, which tends to be backwards from a subject or idea. There’s no way for me to understand the greater meaning of what I’m doing while doing it. Additionally, so many things change in making art— some are failures or successes that can cause epiphanies in the work. I’m interested in following the threads or clues the practice offers, which I hope leads to new or discursive approaches— I like to be surprised.

One for the road… What are you unafraid of?

Illegibility. Failure. Poetry.