Interview by Ana Prendes

Aimée Portioli, aka Grand River, is a composer and sound designer whose experimental electronic music conjures up an atmospheric depth over shifting rhythmic structures. Growing up at the foot of a mountain, Portioli became fascinated by the subtle nuances of the ebb and flow of a nearby river, which partly inspired her stage name and permeates with her compositions.

With a background in traditional music composition, choral singing, classical guitar and piano, Portioli weaves contemporary sonic research with traditional compositional techniques to craft compelling experimental narratives inspired by minimalism and ambient music after living in Berlin for almost a decade.

Her third album All Above, builds guitars, strings, organs, voices, and synths around acoustic piano compositions. The intimate presence of the piano throughout the record, from clean and present constructions to more fluid, distorted, or airy environments, outlines the narrative thread so that ‘all the tracks belong to the same world’, describes Portioli. Mapping her inner moods onto different instruments and arrangements, the delicacy of the acoustic instruments intertwines with the immensity of synths, creating swirling soundscapes that bring about her time-specific feelings to the outside world.

Trained as a linguist, Portioli’s work is deeply rooted in the communicative function of music. On All Above, her sonic vocabulary builds an emotional language of self-expression, transcending any visual or verbal form of communication. ‘We absorb sound. We inhale it; we transform it. Then, it triggers something. I always keep present the powerful communication tool that sound is’, says the artist.

All Above follows her 2020’s album Blink A Few Times To Clear Your Eyes and 2018’s Pineapple, on which the influence of electronic rhythms was still dominant. As a producer, Portioli founded the record label One Instrument, where she invites artists to experiment by following specific guidelines – to compose a piece using just one instrument. Following the release of her own track with a Korg MS-20, One Instrument has released over 20 works, including recent tracks by Pluhm, Suren Seneviratne, and Elisa Batti. As she mentioned in another interview with CLOT, limiting the compositional process to a single instrument allowed her to discover the monophonic synthesiser patiently. She found the overriding of constraints as a powerful creative drive.

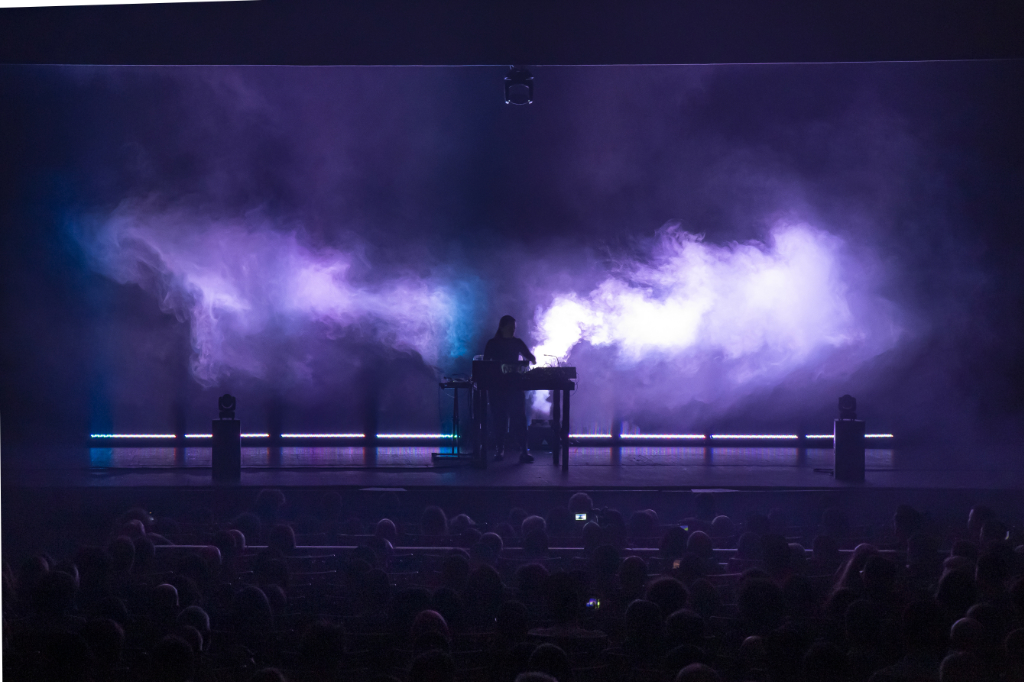

After the premiere at Silent Green in Berlin, Portioli is touring with the live presentation of All Above, conceived in collaboration with her long-time partner Marco Ciceri. The non-linear narrative, constructed through the synchronised interplay of light and sound, alternates explosive bursts with dark spaces for self-reflection and deep listening between our internal and external selves. It becomes a zone of participation in the pursuit of listeners to free up, open out and deepen at the same time, acknowledging the potential of sound to communicate.

Following her show at LEV Festival in Gijón (Spain), we sat down with Portioli to discuss the creative process behind her compositions, externalising intimate emotions through sound, and how her work is all about communication.

How do you approach sound, composition and production?

When I go into the studio and start composing for an album, it’s an externalisation of what I’m feeling at that moment, everything that has influenced me before and what’s around me; it’s free composition. Whether I am feeling sadness, joy, fear, or I am in a more self-reflective state, I am absorbing all the time and then translating what I am absorbing. My pieces are all moments of what is inside me.

I only make conscious decisions when I have to work on a specific concept. For sound installations, I like to work within a conceptual box that drives the narrative. But when it comes to making pieces, and I don’t want a concept, I really enjoy having that white canvas in front of me where I can express the emotions tied to that specific moment.

All Above feels like such an intimate journey, merging evocative acoustic instruments with breathy electronic sources, anchored by the ever-present piano in multilayered ways. Can you share some insights into the creative process? What is the fabric that wove these songs together for the record?

I worked on the pieces for over two years. It’s the album where I experimented much more with fusing electronic sounds and acoustic instruments. As you mentioned, the piano is very present throughout the whole album, deliberately in many different ways. In some compositions, it’s quicker and more precise; in others, it is more distorted and fluid. I consistently record with the same piano in my home studio, even with the same microphone. It took me a lot of experimentation to find the exact sound I wanted to get out of it, but then I stuck with it throughout. That’s what makes them belong to the same world.

When an album comes out, it’s the moment I share the work that I’ve been doing for so long in the studio. Making it available for somebody else to listen to it feels very intimate, but it’s very exciting.

With your background in classical guitar, piano, and cello, the presence of acoustic instruments was not relevant in your previous albums Pineapple (2018) or Blink a Few Times To Clear Your Eyes (2020). What attracted you to bring them back?

It was a practical reason that my Pineapple has no acoustic instruments. When I moved to Berlin eight years ago and started working on my first EP and album, I had neither my piano nor my cello. But as my interest in electronic music grew, the circumstances allowed me to dive deeper into those sounds and concentrate on not including acoustic instruments. Then after two years, I found a piano and a cello with the sound I wanted and started reintroducing them in Blink a Few Times To Clear Your Eyes. For All Above, it was a conscious decision to integrate the piano and make it a protagonist.

I read that your background is in linguistics. In tracks like Kura and Pretichor, distorted and reverbed voices make an appearance but without much protagonism. How do you incorporate vocals into your works? Has your understanding of language translated into your composition process?

In Kura, I included some verses from Lord Byron’s poem Swimming, recorded by a voice actor. I then manipulated it in terms of the pitch, timbre and equalisation of the voice. I like to include some words, some phrases, but I don’t consider them crucial. I treat them as if they are an instrument. Even if the voice is saying something that has a meaning, it is no different from a guitar or a synthesiser playing a melody. I think of each instrument as different characters in a play, having their own characteristics but with the same importance.

I wrote my dissertation on the communicative function of music. The research into the psychology of how sound triggers particular emotions and subverts certain behaviours was very enlightening. We absorb sound, we inhale it, we transform it, and then it triggers something. Every sound is a chance to convey something. Although I do not work as a linguist, I always maintain present the power of sound as a communication tool, which is a crucial element in my work.

Your All Above live show brings the intimacy of the album on stage, crafting a non-linear narrative where the light and sound interplay alternate explosive bursts with blacked-out spaces for deep listening. What was the experience of designing the performance for the album like?

This is my first time designing a tour tied specifically to an album. Going from the studio to the stage is always a very complicated process. Firstly, the ease of access and experimentation with instruments in the studio has to be scaled down. Then, some key questions come into mind: How do I want to translate a personal listening experience into a collective one? How do I want it to be perceived by someone in a physical venue? What are the most feasible technical aspects? When creating a live show, I feel like I’m standing at the foot of a mountain I must climb. But then, when you get to the top with the whole idea, you run downhill. I always have to climb this mountain of creation. Besides, designing a live show is much more about decision-making than the freedom to compose an album.

On the lighting and stage design, I worked with my long-time collaborator Marco Ciceri. We have created performances with video projections in the past, but this time I wanted to express the album with a different visual influence by using light design. We wanted to create an immersive experience that enhances certain moments, while leaving others where the visibility is reduced so the audience can focus on deep listening.

We worked intensely together, in a trial and error process of experimentation, to achieve the synchronicity of light and sound for the experience we wanted. We encounter that the vibrance of the colours, the shape of the reflections, and the smoke distribution vary according to the size and architecture of the venue. It has been fascinating and surprising to experience how each performance becomes somewhat site-specific.

Considering the importance of communication in your work and what it involves in revealing the intimacy of your studio, how do you envision audiences engaging with your music and performances?

When I compose, I try not to think too much about the audience; otherwise, it could interrupt the creative flow of composing. For the live shows, I have a very clear idea of the order of the pieces and how I want to play them because I want to create a concrete musical timeline.

But I like to put myself on the other side and imagine myself as a listener. I know what I like to listen to when I go to a concert. Sometimes it’s not easy because I’m always very critical as a listener of my material. But I usually ask myself, what would I like to hear now? I spend a lot of time working out the details and being precise. As I said, it’s all part of the whole communication process.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

There are many more layers to this profession than just composing music. Overthinking the dynamics of the music industry could dramatically hinder your creative process.

Also, I try not to think too much about the end goal. The time you spend worrying about what will happen, you’re not enjoying the process. In the end, what we have is just a process because we don’t even know when and if we will reach a certain goal.

You couldn’t live without…

Contact with nature. It reminds me of what is important and gives me another perspective of myself, of where I am and what I am doing.