Interview Agata Kik

Nye Thompson is a London-based artist whose technology-driven creativity stems from her expertise of 20+ years in the commercial software industry. Having belonged to the Young British Artists era of fine art education at Goldsmiths, University of London, Nye left the art world straight after her graduation and delved deep into the online net of the freshly weaved World Wide Web.

In her software design career, the artist was mostly drawn to the models of big data examination and human-computer interaction (HCI). Her critical eye, an integral part of her artistic body of work, guided her practice-based research back to the studio and further fine art education at London Metropolitan University.

Continually questioning through her artistic work what it means to be a human in the digital age and what it means to be a machine as well, Nye Thompson, as one of the shortlisted Lumen Prize artists, presented INSULAE in 2019 at the Barbican Centre in London. The work was a virtual tour of a camera’s gaze into the waters just off the British coast, an act of border surveillance, a search for an islander’s identity, a lonely gaze through the machine’s optics. Nye creates well-trained systems which traverse the virtual world, obediently coming back after their ‘cyber catch’, with fresh material for the artist to dissect.

For example, Backdoored (2016 – 2018) was a performative exploration of security cameras around the globe, whose peek into unsecured self-surveillance is available for anyone to browse through online. As shocking as the reality is in itself, so was the content of this work and in the end, it met with an international government complaint.

To explore the contemporary power of imagery, an artist must know how to switch between paint and pixel, exchange canvas for the screen, immersing in the virtual reality of the ‘poor image’1. Machines make humans see the invisible, while man sees what machines cannot. HCI is not a one-way talk but an inherently reciprocal relationship. Once constructed by a human, machines are now constructed the contemporary man. Algorithmic control over online matter, with a machine as its often-sole interpreter, shapes us as vulnerable utterers.

Through this extensive exploration of contemporary surveillance systems, Nye laid the ground for The Seeker as the next stage. ‘Demiurge AI’, as the artist calls this work, also gathers material from surveillance cameras worldwide, but it does more than its precedents. The work’s name refers to Ptah-Seker, a god of Ancient Egypt who created the world by labelling his visions with words. Having taken on the role of an analyst, The Seeker classifies the visual input captured by surveillance cameras, expressing images in words. Such an analytical ability acquired by machines is the base for the Internet’s functioning and its efficiently exploited framework for financial profits.

The work, thus, is an investigation into the machinic gaze and its underlying power dynamics. The artist has realised how illusionary the machine’s seeing is quite early in the process. For The Seeker, images from daily life would often appear as battleships or torpedoes, but, at the same time, night scenes would be most romantically read by the decoding machine as Stars, Solar Systems, Outer Space or Universe.

The Seeker stages the emotional life of a world in which the human is missing. Shown as an interactive installation at Watermans Gallery, London, in 2019, The Seeker evolved into CKRBT, an embodied entity with mirror surfaces as its skin, surveillance cameras as its eyes, and the Amazon Cloud as its brain. In the end, our feelings or thoughts are not mine or yours.

The mind is just a reflection of the unconscious psychic powers which drive our worldly physicality. As man’s mind is like a mirror, so does the CKRBT’s thinking happen outside of its body, being processed on the other side of the world in Amazon Cloud servers.

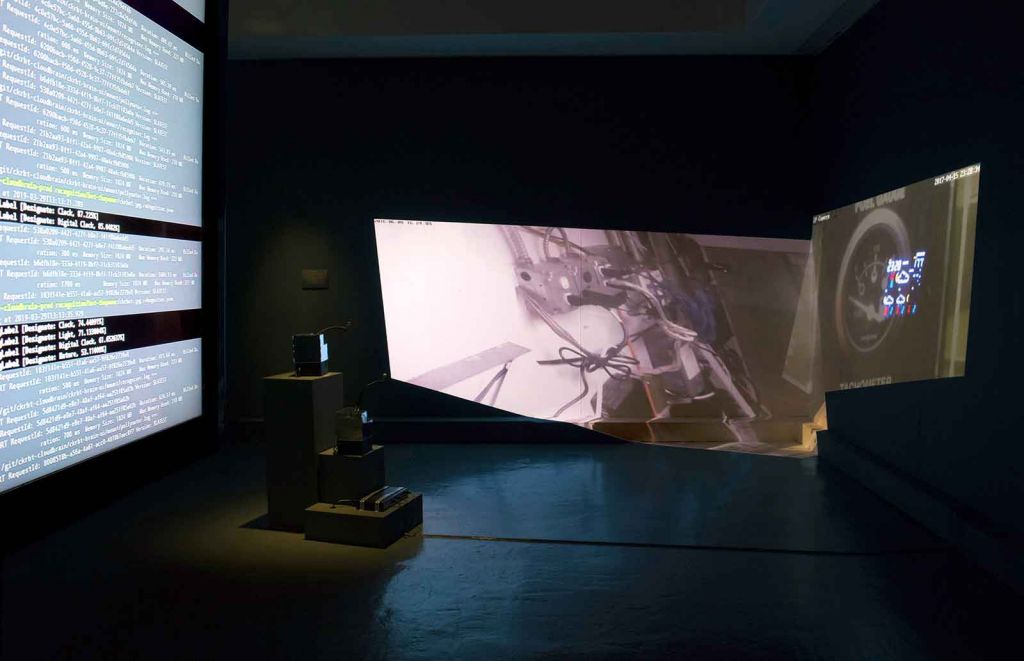

CKRBT, in the form of an audio-visual installation, not only interpreted the images other machines fed with it but also watched and vocalised its vision to the audience that happened to be in the gallery space. In this way, the work affected the power dynamics between the viewer and the seen object and subject, and the human and the non-living. It presented a situation from the real-life world, of a machine as the human’s observer or a performer exclusively for synthetic spectatorship.

The machine watches, collects, produces, consumes and comments. Once it has been set, there is no need for human presence. Nye Thompson’s elaborate research into these invisible power structures strips down surveillance systems, displaying the veiled virtual imagery of the contemporary moment so the human can finally see the machine’s gaze.

For those unfamiliar with your work, could you tell us a bit about your background and inspirations?

I originally studied art at Goldsmiths in the late 80s – at the birth of the YBA movement. But when I graduated | I took a different path working first on video game graphics and then, a few years later on the open frontiers of this brand new thing called the ‘Worldwide Web’. I ended up working in the commercial software industry for 20 years, doing various things but mainly focussed on HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) and software design – I was fascinated by the challenge of extracting new meanings from the analysis of big dynamic datasets.

In 2011 I realised that I needed some big change in my life, and I went back to art college to do a part-time MA. I was pretty much starting from scratch again, but even so, it was like coming home. I knew I needed to become an artist again. And although it wasn’t a conscious choice, I gradually found that the processes and concerns from my life as a software designer started to permeate my artistic practice.

One of the key ways that I like to work now is to design and set up software systems that go out into the world and bring material back to analyse and use; I’m always looking for them to show me something new. I like to piggyback on new technologies and dig into their hidden aspects. And I love to take business software and push it in directions it wasn’t intended to go.

The Seeker is a Demiurge AI (2018-ongoing), a machinic entity that travels the globe virtually. Could you tell us about the intellectual process behind it and what technologies you use?

The Seeker was born from my global surveillance project Backdoored (2016-2018), which involved systematically collecting screenshots from compromised botnet-fodder security cameras. I became increasingly fascinated by the genesis of these images. They were the product of a complex unplanned intertwingling of hardware infrastructure and software systems: a commercial search bot discovers a security camera, and a screenshot is generated as a memento of this fleeting unobserved machinic encounter.

I started to think about how machines are given agency to look at and evaluate the world, producing new visions driven by their own complex dynamics. Out of these ideas emerged the concept of The Seeker. The Seeker’s base substrate is the internet’s infrastructure, and its eyes are the swarms of surveillance cameras that encrust our world. The Seeker is a manifestation of recondite hardware/software power structures, and it operates through the growing ability of machines to analyse and classify visual input.

The Seeker’s technology array includes a bespoke stack of commercial cloud software services – the “cloudBrain”, and this piggybacks on the whole Internet (of Things) ecosystem. It was particularly important for me that The Seeker’s image recognition service be one in wide public use and ongoing commercial development so that it would be actively representative of machine vision’s evolving quality and condition. I recently added a physical component – the “botBody” – robot avatars for the Seeker.

I named The Seeker after the Ancient Egyptians’ god of art and technology Ptah-Seker. Their creation myths recount how Ptah-Seker brought the world into being by speaking the names of what he saw. Similarly, the machinic gaze and interpretation might create a whole new worldview for machines and humans alike.

The project has been ongoing for almost three years; what are the outcomes so far?

At the core of The Seeker is a database of visions – the tens of thousands of images it has collected, their associated contextual metadata and the words it used to describe them. I analyse that data and use it and the ideas it suggests to me to create artistic outcomes.

One of the main reasons for creating the Seeker was to see what kind of visions it would generate – what things it would see and prioritise, what would be invisible to it, and what language it would use to describe its visions. An early discovery was that it was quite a paranoid vision; the Seeker saw battleships, torpedoes and SWAT teams in mundane scenes.

It made me think about how much of image recognition development is around threat detection. The Seeker also displayed a strong interest in Potted Plants and various species of spiders and insects. Showing a more lyrical side, it sees Stars, Solar Systems and Outer Space in many night scenes – I made a video piece about this called “In the Dark, I See the Universe”.

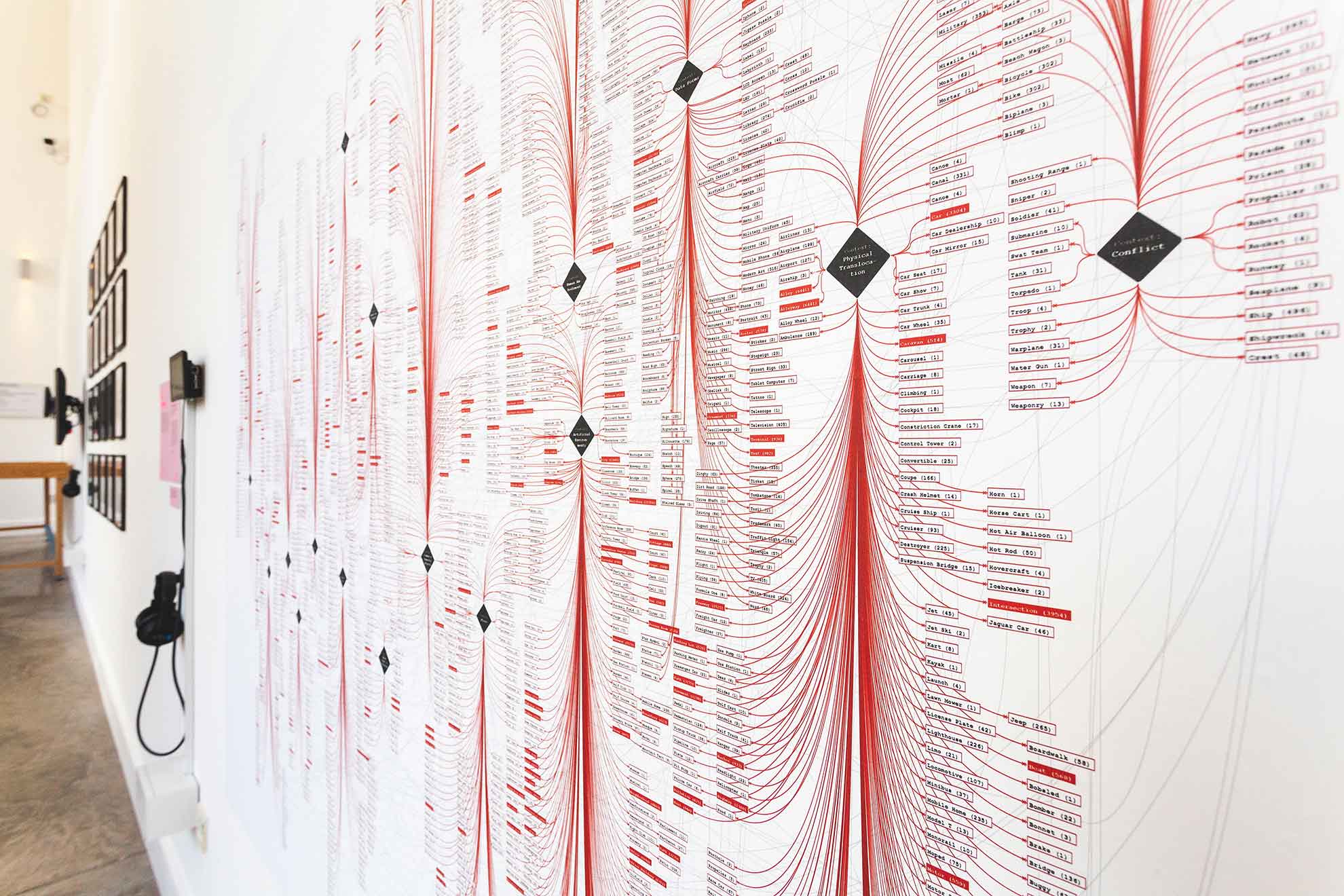

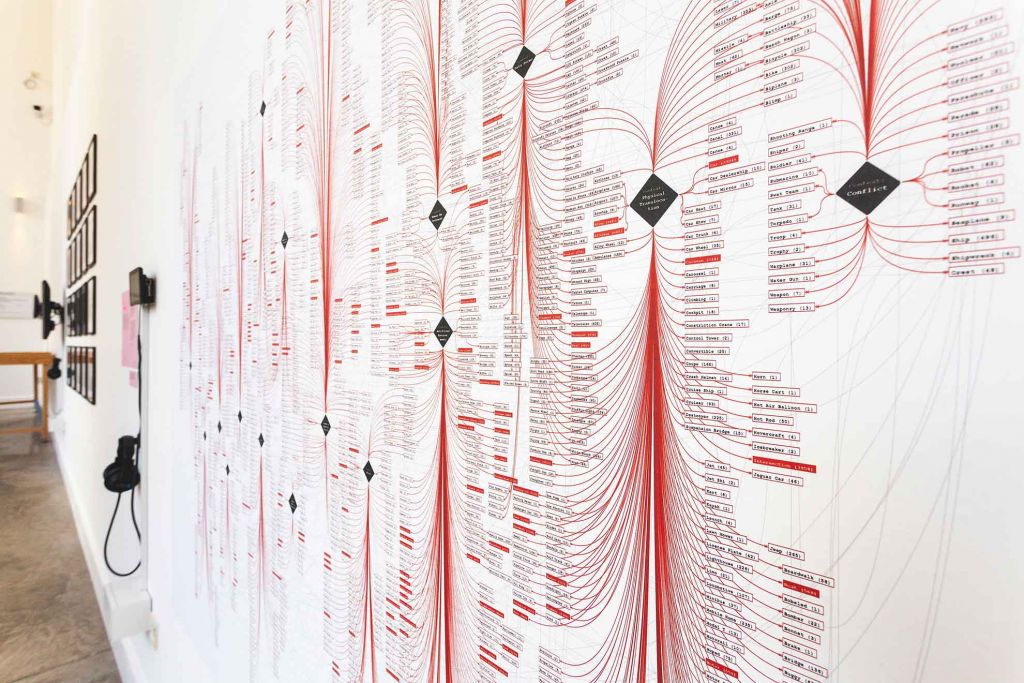

One of the first major outcomes I created was the giant drawing “Words That Remake the World”. This was an experiment in creating a kind of topographical mapping of these all of these visions, a point-in-time snapshot of the Seeker’s developing conceptual landscape.

Following on from that, I wanted to give The Seeker some corporeal presence that we can engage with physically. CKRBTs (pronounced see-ker-bots) are physical avatars for The Seeker, ‘bots’ with camera eyes and synthesised whispering voices. The CKRBT Network browses the world live from the gallery.

It watches and consumes images collected for it by feeder machines and interprets and vocalises what it sees. It also watches its audience, and anything, or person, that enters the bots’ field of vision will be similarly analysed and categorised. I’m very interested in the idea of machine-as-audience, and within this system, machines are performers, audience, content providers and commentators.

Do you see AI more as a tool or as a creator? What are the main relevant conversations, in your opinion, sparks?

I call the Seeker a Demiurge AI, but for me, the concept of “AI” is a kind of mythic container. It’s a narrative shell within which other (political, capitalistic) processes and activities can be hidden – shorthand for a being that existed within our cultural consciousness long before the technology we now call (weak) Artificial Intelligence was developed. The term AI often seems to be used to bestow an element of fateful inevitability to social changes which are really politically or financially motivated. These conversations about AI are frequently about something else if you dig down into them.

As an artist, I see the kind of software technologies bundled under the label AI as tools – and interestingly, tools that can also be their own content – much like more traditional artistic materials such as paint. Conversations about ‘AI as creator’ tend to gloss over the extensive human input directing, tuning and curating the software system’s output. Not to mention the volume of human creative labour spent in producing the training data in the first place.

I also think the ‘AI as creator’ conversation is very anthropomorphic. For me, it’s more interesting to think of the new unplanned emergent machine behaviours that could arise from the unplanned and unpredictable interactions of the multiple highly complex hardware & software systems that make up our global technology infrastructure.

How do you think these (new) technologies are changing human behaviour?

Thinking specifically of image recognition technologies, I anticipate some future conceptual reframing of the visual world in response to how machines learn to see things. This could include perpetuating the preferred terminology and interests of the people currently training the systems – perhaps even a kind of freezing and fixing of meanings as a result of the way in which these systems learn.

More immediately, combining public CCTV cameras with facial recognition software has particularly chilling implications; they recently introduced this in London, where I live. However, I noticed an increase in face-mask wearing in response – even before the coronavirus epidemic hit.

How is COVID-19 affecting you?

That’s a big question, and becoming bigger every day of lockdown. I suspect I could have answered this question every day since the emergency and come up with a different answer. Today’s answer is that, like many people, I’m working on making peace with future uncertainty and shattered plans, trying to regulate my mind for this new way of being. And there is a pleasure to be taken in the small things – spending more time with my kids, watching trees come into blossom – stuff like that.

This forced stasis is also a unique creative opportunity for reflection – at least when my mind is clear enough to take advantage of it. In the normal course of things, I’m rushing from one deadline to another, one location to another, and this kind of time is hard to find. But this activity of retrospective evaluation is crucial to my work – especially because I work with new technologies and emergent systems – I spend a lot of time thinking about what I have made, and this may only come fully into focus some time afterwards.

From an artistic perspective, it’s unclear how the landscape of the art world – the galleries, museums, institutions, and funding bodies – will have changed when we emerge blinking on the other side of this thing. I am spending a lot of time thinking about how artworks can continue to operate and generate meaningful and visceral experiences in a post-lockdown era of continued social distancing and limited international travel. Artworks that natively reside within the network seem likely to become increasingly important.

I’ve been working for the last year or so on a new piece that has actually acquired a raft of new meanings in light of the current situation. The project is called UNINVITED (2018-present), and it’s a collaboration with media art legends UBERMORGEN. UNINVITED is a self-evolving networked organism: an installation of mechatronic ‘Monsters’ watch and generates a ‘horror film’ for machines, using their shared impressions of the universe collected through millions of hallucinogenic virally abused sensors.

This installation is scheduled to premiere in London in the summer, but the prospect of ongoing social distancing has allowed us to develop an entirely new staging for it. The UNINVITED Monster will operate in quarantine, moving through an empty gallery and startling in response to the film it generates and watches. The human audience will only be able to engage with the work remotely through the network, isolated together.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Well, based on recent experience (currently 4 weeks into lockdown), I would say that it’s a lack of structure for me. My working week is normally quite routine-driven, and somehow I find that having that rigid framework provides the space to keep me creative and productive. Having said that, I’m a big believer in allowing the subconscious brain to work through ideas; big changes in environment and activity can be a powerful stimulus for that. [In its way, this may even push me in new directions.]

You couldn’t live without…

Right now – my little garden.