Interview by Meritxell Rosell

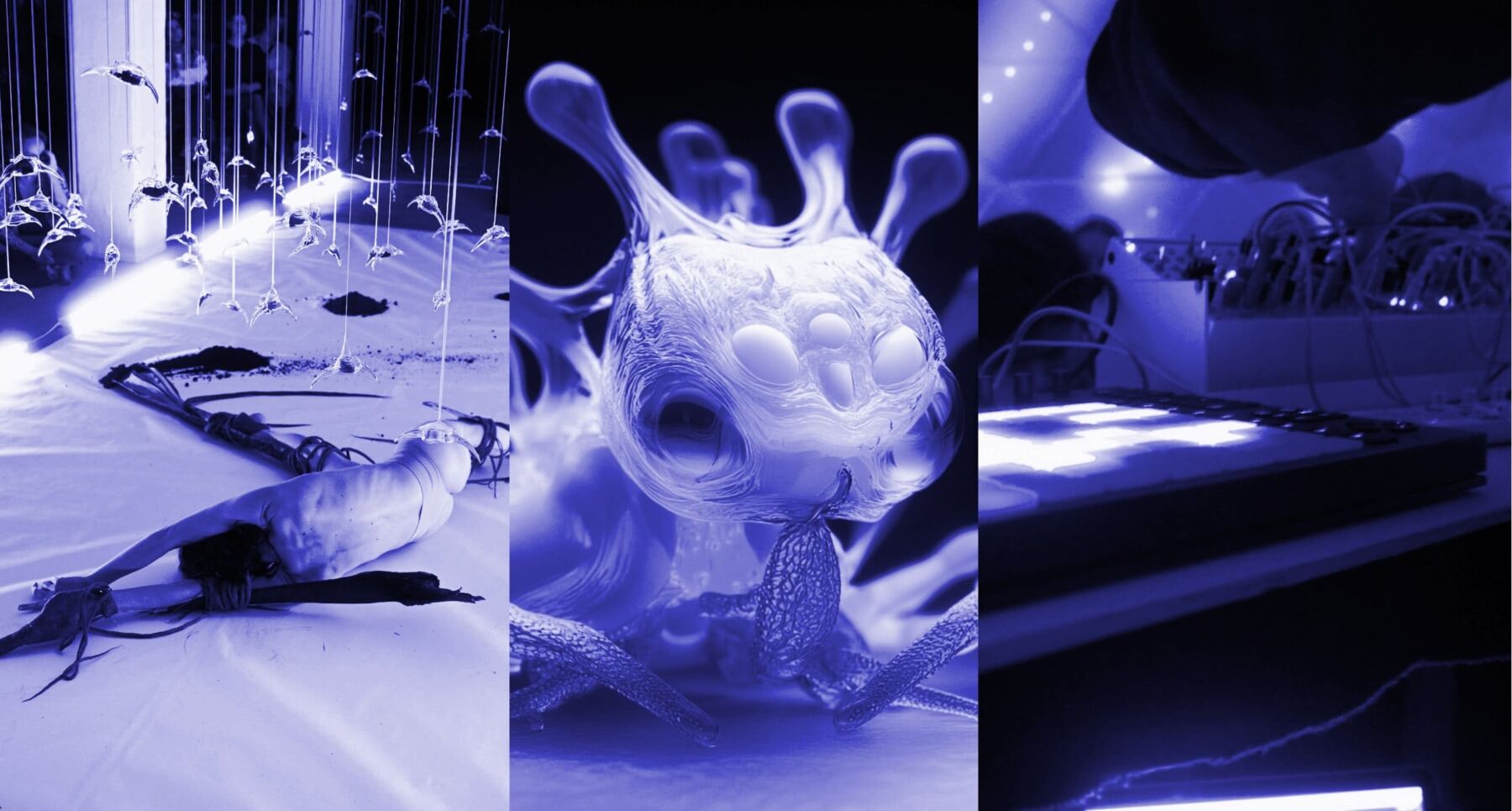

Rafael Anton Irisarri has emerged as a leading figure in experimental and ambient music, crafting intricate sonic worlds where emotion and atmosphere converge. His work challenges listeners to engage deeply with sound, not just as an auditory experience but as a means of exploring memory, identity, and transformation. Layers of drones, field recordings, and subtle melodies weave into compositions that evoke a sense of place and time yet remain unanchored, inviting personal introspection.

With a career spanning over two decades, Irisarri has carved out a distinct niche in contemporary sound art. From Daydreaming (Miasmah Recordings 2007) to the recent Façadisms (Black Knoll Editions 2024), his albums offer immersive experiences inviting listeners to confront temporality, reflection, and transformation themes. His compositions unfold like vast landscapes, where textures converge and dissolve, evoking a sense of place that is at once familiar and elusive.

In Façadisms Irisarri addresses the idea of façades, both literal and metaphorical, as he delves into the tension between authenticity and deception. The album’s textured soundscapes evoke a sense of peeling back layers to reveal hidden truths. The juxtaposition of immersive drones and decaying noise creates a sonic landscape where what is concealed becomes as significant as what is revealed.

An enthusiast of languages, Irisarri´s work is imbued with a playfulness in the rhythm and tonal quality arising from those. As if each of the different languages, each with its distinct rhythms and cadences, finds a voice in the textures and tones of his soundscapes, creating a dialogue with sonic expression.

Sirimiri (Umor Rex 2018) offers more intimate meditation inspired by the persistent, quiet drizzle for which it is named (a Spanish word originating from the Basque language, which even has a more suggestive pronunciation). Here, Irisarri shifts focus to subtlety and fragility, crafting soundscapes that feel like fleeting moments—raindrops tracing patterns down a glass or the whisper of wind across a field. The music unfolds slowly, drawing the listener into its gentle rhythms and enveloping warmth, evoking a sense of quiet contemplation.

Other albums like Solastalgia (Umor Rex 2019) and Peripeteia (Dais Records 2020) further Irisarri’s exploration of displacement and change. While Solastalgia captures the anxiety and sorrow linked to environmental degradation, Peripeteia (which includes collaborations with Lawrence English and Yamila among others) reflects on personal upheaval and the cyclical nature of history. His ability to meld analogue textures with digital processing enables these works to resonate on both a visceral and cerebral level, presenting sound as a medium to grapple with the complex interplay between our surroundings and our inner world.

As he continues to explore the connections between identity, environment, and the passage of time, Irisarri’s work reminds us that sound can be a powerful map—one that charts not just the spaces we inhabit but the journeys we undertake within ourselves.

Your music is often described as transcending genres, merging ambient, drone, and classical elements. Could you share your early influences (doesn’t necessarily need to be musical; for example, La Monte Young recalls growing up in Idaho where he was exposed to the constant hum of wind, electrical power plants, and machinery), which played a significant role in shaping his interest in sustained tones and drone music? Was there a particular moment or experience that led you to experiment with the unique sonic landscapes you create today?

My early influences stem from the unique environment and culture of my childhood in Puerto Rico. The island’s sounds—especially the ocean and the crashing of waves—shaped my perception of music as something that interacts with nature. The music press has often described my soundscapes as “oceanic waves of sound” or “a hurricane passing over an ocean, gathering heat and force while simultaneously cooling the waters below.” Growing up on the coast of a Caribbean island that experiences so many tropical storms and hurricanes instilled in me a fascination with those elements. I think I subconsciously try to recreate them through textures and atmospheres, which I later incorporated into my creative explorations and musical output.

A pivotal moment for me was hearing The Orb for the first time as a teen. It opened up a whole new world of sounds and kicked off a long journey of musical discovery. From there, I started experimenting with combining elements from totally different styles of music—like blending ambient textures and drone sounds with dub syncopation or the weight of heavy metal guitars—to create unique sonic landscapes. My exposure to classical music (especially works emphasising minimalism and sustained tones) also fueled my desire to explore these ideas further. Artists like La Monte Young and Terry Riley and minimalist composers like Arvo Pärt have heavily influenced my approach to composition, helping me appreciate the power of repetition and simplicity. I feel like my unique mixed cultural heritage, and personal experiences come together to create a sound that doesn’t fit neatly into any specific genre or style yet feels distinctly my own.

Delving into your sound feels deeply meditative, almost like a process of excavation, uncovering emotional or sonic layers. When you begin a new project, do you adopt a particular ritual or mindset to enter this creative space? How do you navigate the transition from idea or feeling to tangible sound, especially when dealing with abstract concepts?

For sure! My creative process is kind of like therapy—more like digging within myself to uncover the emotional core. I don’t have a strict methodology, but I do have some rituals that help me get into the zone. I love waking up really early; there’s something about the sound of the world at 6 AM that feels so fresh and crisp. In that quiet time, I often read or write down ideas in my notebook. When it comes to turning an idea or feeling into sound, I embrace the abstract. I usually start with a concept that speaks to me and let it guide my exploration.

Sometimes, I’ll sketch out rough sounds or just dive into some improvisation. From there, I layer textures and let the piece evolve naturally. I believe in going with the flow and trusting the process. Often, what starts as one thing turns into something completely unexpected, and that’s where the magic happens. Ultimately, it all comes together to create music that comes from a genuine place connected to my emotional state at a given time.

Your compositions often emerge organically, as if they are living, breathing entities rather than fixed pieces of music. Do you allow spontaneity to guide your process, or do you start with a clear structure in mind? How does intuition versus intentionality play a role in shaping the direction of a track or an album?

The way I work begins with improvisation, which I always record first. I then search through the recording to find moments that stand out—motifs or sections that can serve as building blocks. Once I’ve gathered a palette of sounds and motifs, I begin arranging, editing, and composing from there. Often, this process is intuitive, though at times I have a specific sound in mind. For example, the other day I was improvising with a new fuzz pedal on my guitar and recorded a riff on my voice memo. That riff became the foundation for a piece, as I could already hear a vocal melody over the main motif, which eventually turned into a composition for fuzz guitar, cello, and choir. Moments like these feel incredibly special.

The production process and techniques I use play a crucial role in bringing these moments to life. As I mix my work, I rely heavily on automation and LFO modulation to manipulate the parameters of hardware, software effects, and synths. This creates dynamic movement and variation throughout the tracks, keeping the pieces in constant motion. I apply the concept of ‘invisible hands’ from modular synthesis to my entire studio, treating it as both a creative tool and an instrument in itself. This approach breathes life into the recordings and pushes them in new, surprising directions. Curiosity is key—staying curious about possibilities in the studio (and in the world at large) is essential.

Identity resonates throughout your music (maybe shaped by your Basque heritage and your experiences living in different countries and states across the US). In addition to speaking several languages (among those Basque, Spanish, Italian, and English). How has all this background shaped your compositional process? And, for example, do these languages’ rhythms, intonations, or sonic textures subtly inform how you shape and structure your sound?

Absolutely, my complex identity plays a significant role in the music I write. Having a mixed European background and living in various states across the U.S. has influenced my compositional process. Each place I’ve lived has contributed its particular sounds, rhythms, and stories, blending everything together—from the Afro-Caribbean beats I heard growing up to the metal and grunge I encountered in the U.S. mainland. Knowing different languages adds layers to this complexity.

The rhythms of these languages find their way into my music, subtly informing how I shape and structure sounds. For instance, the adaptability and intonation of English, the sing-song quality of Italian, the cadence of Spanish, and the percussive qualities of Basque—think of the affricate consonants Ts, Tx, and Tz in Euskara, which sound like hi-hats to me—can all inspire rhythmic patterns. While most of my music is instrumental, each language opens up a different avenue of creativity, giving me a much larger palette to draw from when composing. Ultimately, my identity and life experiences contribute to an artistic practice that’s not just about sound but also about storytelling, culture, and connection.

And identity too, has been a recurring theme in your work, with many of your albums reflecting personal, social, and even political struggles. How do you navigate the fine line between personal catharsis and broader social commentary in your compositions? Do you think music as an abstract form can communicate these deeply human experiences effectively?

I’m not necessarily trying to create social commentary in my work, per se. I think living in this current timeline is a natural byproduct. Whether we like it or not, we are influenced by what surrounds us, and our art becomes a reflection of that. We’re all products of our time, and art tends to mirror what’s happening in the world at large. Even escapist or seemingly vapid art is a reaction; it can provide a respite from the struggles we face.

In my case, I’m not looking to provide answers, point fingers, or virtue-signal. For me, it’s more about how I react to what’s going on around me and how it makes me feel. Often, I’m just trying to make sense of it and process those feelings through my compositions. Navigating this line happens very organically for me. With the instrumental music I create, the absence of lyrics allows me to reflect on a theme without necessarily telling people how to think about it. This leads listeners to draw their own conclusions. Abstract music can help facilitate this kind of contemplation.

Similarly, your compositions often evoke a sense of place but remain ethereal and unbound by specific geographical or cultural markers. How do you think about ‘place’ when creating your soundscapes? Is it a conscious process of deconstructing your surroundings, or do you subtly allow the environment to seep into your work?

I find that the sounds around me greatly influence what I create, particularly my emotional responses to that aural stimuli – they often blend seamlessly into the textures I develop. It’s such an intuitive process for me! I tend to respond to the atmosphere and feelings of a space rather than trying to pin it down. This approach opens the door for a broader interpretation of place—something that resonates with listeners on a personal level, letting them project their own experiences onto the music. For instance, I love to take a field recording from a specific spot and decontextualize it, mixing it with other sounds to craft an environment that feels both alien and familiar. Ultimately, I’m really interested in the interplay between memory and place. I aim to create soundscapes that evoke feelings and memories, allowing each listener to find their own connection to the idea of ‘place.’

With the rapid technological advancements in music production, how do you see the relationship between human expression and machine-driven processes evolving? Do you ever fear that these technologies, while increasing accessibility, might dilute sound art’s raw, emotional aspects?

I’m not so sure. When synthesizers first emerged in the 1960s and 70s, they were often viewed with scepticism, as if they might replace musicians altogether. However, over time, they transitioned into being seen as just another tool in the creative process. With the introduction of MIDI in the 1980s, synthesizers gained a whole new dimension. MIDI allowed different instruments to communicate with one another, enabling musicians to create complex arrangements without being limited by the physical capabilities of their instruments. It opened the floodgates for experimentation and creativity, allowing artists to layer sounds, control parameters, and even trigger effects from a single controller.

I view the potential for machine learning to enhance the creative process similarly—whether by controlling modulation parameters in synthesizers or developing innovative instruments— it’s truly intriguing to me. As long as a human guides that creativity, all the tools at our disposal can be fantastic. For the past 25 years, though, the way technology has been employed in pop music has often been detrimental—just think about the overuse of auto-tuning and quantization that characterizes many modern big records. This has led to a homogenized sound across genres, reminiscent of a contemporary version of “Schlager”—inoffensive, bubblegum pop. In the realm of pop music, only a handful of artists are truly pushing boundaries, like Arca and the late, great SOPHIE. Their work feels incredibly edgy and challenging, but it is definitely not tailored for the mainstream. Their innovative use of technology seems to drive the conversation in a more meaningful direction. Unfortunately, the mainstream has a lot of catching up to do. And, of course, AI-generated art, while funny sometimes, is absolute rubbish. I think the quest by social media companies for endless content (and revenue) is driving much of that.

Intricate layers of sound, blending processed field recordings, synthesis, and acoustic instruments… Can you talk us through your creative process in terms of sound design? How do you decide when to use organic sound sources versus digitally manipulated textures, and how do you balance the two?

Absolutely not, it’s a BIG guarded secret—proprietary information! Haha! Of course, I’m happy to share, but I have to say that I don’t follow a specific methodology for my sound design process. I can start with anything that inspires me, and I believe that’s the most crucial part: inspiration. The tools I use, whether it’s an old tape machine or the latest version of Ableton, matter less to me than the initial spark of creativity. I often balance organic sound sources with digitally manipulated ones. To add another layer of complexity, I might even manipulate a digitally sourced sound using an analogue machine—like running a VST synth through a tape machine.

For me, it’s all about creating a sound palette that feels unique to my circumstances. When I first started, I had limited equipment at my disposal, so I adapted to those limitations. I learned to make compelling sounds using only what I had available. I incorporated these limitations into my creative process, allowing them to drive my aesthetic. Instead of striving for a guitar sound that required thousands of dollars worth of gear—think of David Gilmour’s pristine guitar tones —I focused on finding something interesting with the little I had. This approach proved far more rewarding and has shaped how I create ever since. I’ve become quite adamant about using limitations as a creative tool.

You’ve mentioned using unconventional tools and techniques in your music, from modular synthesis to tape manipulation. In recent years, is there a particular piece of hardware or software essential to your creative workflow? How do you feel these tools allow you to push the boundaries of your sound, both technically and emotionally?

Oh yeah, many actually. I absolutely love playing the Prophet V synth. It’s a very flexible and inspiring instrument. I also have a few effect boxes I really cherish and enjoy running sounds through them and playing the effect box as an instrument. I could easily play with my CXM1978 pedal for hours. I’m a heavy Ableton user, and it’s an integral part of my workflow, particularly when improvising with the guitar. I’ve built it into a customized system that I can use as an instrument in itself. That’s been the most satisfying thing to do.

In Solastalgia (Room40, 2019), you addressed the psychological distress caused by climate change and environmental degradation. Could you expand on how you translated such a complex, intangible feeling into sound? Were there any particular field recordings or sound design techniques that captured this emotional and environmental disquiet?

When I started to conceptualize and compose Solastalgia, I was visiting Iceland in July 2018. During my time in the country, I collected many field recordings, which became the foundation of the pieces. I witnessed firsthand the thinning 700,000-year-old glaciers of the Snæfellsnes Peninsula and the massive Snæfellsjökull volcano, with its receding ice cap that scientists predict will be completely gone by 2050. It’s hard to be a climate sceptic when the evidence is right in front of you, so I took a picture of this volcano—a grainy, long shot shrouded in ominous fog. This image became the album cover, marking one of the few instances where I created my own artwork for a release. Much like the image that adorns its cover, this album represents a perspective focused on the emotional aspect of habitat loss. I don’t claim to have answers to solve our current climate crisis. This crisis won’t be solved by one person. Our impact as individuals is just a drop in the bucket. We need policy change at a larger scale—mobilization from our elected representatives to create solutions with significant impact. Companies that pollute on a grander scale, like factory farms, must also find sustainable alternatives.

Reconnection with the past greatly influenced the sound and compositions of Solastalgia, as I reflected on how our history shapes our present. I spent my childhood growing up poor in a single-parent home in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Experiencing hurricanes in the Caribbean island was incredibly disruptive. I vividly remember showering with buckets filled with rainwater for weeks after Hurricane Hugo in 1989. Our home lost electricity and running water for almost a full month. One downside of relying on rainwater buckets for our needs was the breeding of mosquitoes. Mosquitoes are nature’s most lethal killers, claiming more human lives than any other creature on the planet. In Puerto Rico, nearly every storm-related crisis (of which there are many as we are in the path of numerous storms and hurricanes) is followed by a dengue fever outbreak. I nearly died from the hemorrhagic variety of dengue fever as a kid (in fact, I had the disease twice, but that’s another story).

Having firsthand experience of how dire things can become after a major disaster, I was deeply disturbed by the lack of empathy and response from the U.S. government following Hurricane Maria in 2017. As many people know, Puerto Rico is a colony of the U.S., and despite the population being American citizens, they are often treated as second-class citizens. I felt a strong need to help someone, even if it was just one person. I invited a childhood friend to come to New York and spend a few months with us while the island was without electricity. A few days before he arrived, he sent me a picture of the modest home I grew up in (I lost all my possessions in 2014 after a truck robbery, including a lifetime of photos) to show me how it had fared after the storm, as well as a friendly “Hey, do you remember this place?” kind of gesture. That picture triggered something in my brain—many long-forgotten memories buried in time.

This experience inspired me to reconnect with some of the music from my childhood. For example, “Decay Waves,” the opening track on the album, is inspired by the string sections of a famous song called “El Cantante” (The Singer) by Héctor Lavoe, an iconic Puerto Rican salsa singer. Growing up, I wasn’t into salsa; it was only as an adult that I came to appreciate much of the music I’d hear on the radio at the grocery store. My mom was into English-language pop/rock, mostly listening to ’80s pop like Phil Collins and Chris de Burgh, along with Iberian artists like Joan Manuel Serrat, Hilario Camacho, and the Spanish icon Raphael (I have a strong connection to the Iberian Peninsula through my heritage). Salsa wasn’t something I heard in my household otherwise, only on local television or in public.

Eventually, I studied and learned the syncopation of “clave.” If you listen closely to the music, the movement of the sounds is all syncopated (though it can be pretty hard to follow, as the BPM of the track is quite comatose, but it’s there). To translate the complex feelings of loss and disquiet into sound, I added field recordings I captured in Iceland, allowing the environment to speak for itself. The stark contrasts of melting ice and volcanic activity were woven into the fabric of the music, creating an emotional landscape.

As a nod to this musical inspiration, I asked my dear collaborator, Argentine musician and singer Leandro Fresco, to contribute vocals to the composition, which he kindly recorded for me in Buenos Aires. Feeling fairly confident, I even dared to sing along myself, and layered my voice into the track. Other songs on the album are a nod to my metalhead years, playing the so-called “Devil’s tritone” chord, while other pieces pay homage to my Iberian heritage by using Eight Tone Spanish scales, which trace back to the Jewish quarters in Andalusia during medieval times. The combination of these diverse influences and personal experiences allowed me to express the emotional and environmental disquiet I felt, making Solastalgia a deeply resonant exploration of loss and memory.

And in Sirimiri (Umor Rex, 2018) (mention is one of my favourite sounding words in Spanish), the idea of a light, continuous rain evokes a slow, persistent flow of time—something subtle yet ever-present. How did the concept of ‘sirimiri’ shape your perception of time and continuity in compositional terms? Do you see this gentle unfolding as a way of reflecting on temporality, memory, or the passage of moments?

Sirimiri is one of my favourite words too! It comes from Euskera, meaning “fine rain” in Basque. It’s such a beautiful term and one of many Basque words we use in Spanish without even realizing it. Take zanahoria, for instance—it comes from zain horia, meaning “yellow root” (carrots come in many colours, including yellow). Or izquierda, which comes from ezkerra, meaning “left.” I’m such a language geek; I could go on and on!

Sirimiri has always resonated with me – not only is it typical in the Basque country, but also in Seattle, where I lived at a pivotal time in my life. This subtle but continuous drizzle is like the passage of time itself. In this EP, I embraced this idea, allowing compositions to unfold naturally and without abrupt transitions. In fact, this cassette plays continuously, having the same exact material on both sides; the idea is that when it ends on one side, it automatically starts again on the other side. Just as sirimiri gently floats in the air, the idea was to create a flow that felt seamless and immersive. It’s reflective of how I’ve thought about time, memory, and the passage of many fleeting moments throughout my adult life.

The central piece, “Sonder,” took shape during a rough period in my life as a musician. Many years ago, I broke my thumb while on tour in Italy, which made it impossible for me to play guitar. It took several months of physical therapy to regain the movement and strength necessary to play again. During that difficult time, my dear friend Carl Hultgren from Windy & Carl came to my studio, and we spent a weekend improvising together. He played guitar while I worked with effects and synths, running everything through loop pedals—much like I would on my own, but with Carl taking the role of guitarist. It was an absolute privilege to collaborate with someone I’ve admired for over 25 years, ever since I first heard Windy & Carl’s album Depths (1998). “Sonder” fits the mood of Sirimiri perfectly. It reflects an experience I had years ago when I was walking alone through the streets of Donostia, contemplating my life in solitude. I realized that every stranger around me had a life just as complex as my own—something we don’t immediately see but know is there. It’s like the drizzle: at first glance, it doesn’t seem like it’s raining, but walk in it for a while, and you’ll end up soaked. That’s the essence of Sirimiri for me: a reflection on time, memory, and the quiet yet persistent things we often overlook in life.

Let’s talk about your latest album, FAÇADISMS (Black Knoll Editions), which carries a strong thematic resonance with the concept of identity, especially in the context of façades—whether personal, societal, or architectural. How do you interpret the idea of a ‘façade’ about your own identity and creative process? Did you have any symbolic or literal façades in mind while composing the album? how is the concept of duality—inner versus outer worlds, real versus imagined selves explored? Do you think the façades that society builds around consumption and progress are beginning to crack, and how does this tension manifest in the sound textures of the album?

This album carries a duality: while it’s about the unraveling of the “American Dream”—or, as I find it more fitting to call it, the “American Myth”—it also delves into the façades we’ve all built in the age we live in. Think about the personas we project online; the hyper-curated, manicured lives many present to the world through social media are not that different from the Potemkin villages designed to impress Catherine the Great. So, what happens when these façades start to crumble? These are the things I’m really interested in exploring, whether it’s the eroding trust in the institutions that uphold our “democracies in the West” or the façades of freedom we’ve been told we enjoy. Are we truly a free people? Who does this “freedom” serve? Is it just a red herring served up by the ruling elites? Why are we all essentially enslaved to algorithms pushing us “content” 24/7? I’ve been seeing these things for years and questioning not just why they’re happening but who they’re benefiting. It feels like it’s all a façade masking a much more disturbing reality.

I’ve been thinking lately about how the shifts and collapse we’re witnessing now aren’t so different from the late Bronze Age collapse of antiquity. That process lasted many generations, so we probably won’t see the full scope of what’s happening in our lifetime; we’re just catching the early stages of it. I’ve utilized a lot of loops on this album to reflect on the cyclical nature of our history – we are all caught in these cycles that intertwine with one another, creating as a result different interactions and motifs. I’m merely trying to make sense of all this chaos. And well, simply look at the world around you, doesn’t it feel so hopeless? Like everything is starting to crumble. To me is very obvious that what we are currently doing as a species is not sustainable. We’ve been burning down our house, our neighbor’s house, and then some. And this tension informs much of the sounds on the record. There are moments of fury, but also moments of tranquility. There are moments of dissonance, but also of beautiful harmony. But mostly, there are moments of abandon.

In terms of collaborations, you have worked with a diverse range of artists across various disciplines, from musicians to visual artists. How do these collaborations influence your creative process and personal growth? Do you see this exchange of ideas as a form of community-building?

Collaborations have been vital to my artistic practice since I started releasing music nearly 20 years ago. This stems from how I view the recording process. In electronic music, where an artist often takes on the roles of producer, engineer, and performer, I believe that music becomes infinitely more interesting when a group of people are working together toward the same vision and goal. It’s essential to have a community of individuals contributing to something bigger than just one person. Along the way, I’ve been pleasantly surprised many times. For instance, my long-time collaboration with Benoît Pioulard has been incredibly rewarding. Not only have we been making music together for over 15 years, but he’s now a close friend. We’ve shared countless experiences, and that long-standing friendship, filled with mutual respect and admiration, greatly informs our creative process in the studio. We aren’t afraid to express ourselves freely, have honest dialogues, and speak our minds about music or something personal.

And of course, my collaboration with Abul Mogard which has been particularly enriching. Finding a kindred spirit to create music with is incredibly fulfilling, especially as we grow older and become more accustomed to our specific circles. Over the past couple of years, we’ve discovered how much we have in common, particularly in our working methods. Sometimes we joke that we’re like brothers from another mother, separated at birth, so to speak!

In addition to those musical collaborations, I want to highlight the importance of working with other collaborators. For example, Daniel Castrejón, a designer and visual artist who also runs the Umor Rex label, handles all the design work for the Black Knoll releases. He is one of my favourite designers I’ve worked with, and his unique vision and creativity have played a huge role in shaping the identity of the label (and studio), making each release visually striking and cohesive. Similarly, Paris-based Karen Vogt has been key in supporting label communications and management tasks. Her assistance has been invaluable, allowing me to focus more on the creative aspects while ensuring everything runs smoothly behind the scenes. She’s also a brilliant musician and artist, so I’m sure we will also work on music at one point in the near future. Those are the kinds of relationships I’m most interested in fostering and developing—working with kindred spirits from different backgrounds and exchanging ideas and culture in meaningful ways, not just in music, but in life in general.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Conformity and comfort. When you’re comfortable with what you do, it’s easy to fall into a routine and shy away from stepping outside your comfort zone to explore new possibilities. Musically speaking, this is akin to knowing only the C major scale and never bothering to experiment with other scales. Since the C major scale consists solely of the white keys on the piano, it feels very easy and familiar to play in that key. Of course, this is a rather simplistic example, but it illustrates a crucial point: for great work to emerge, one often needs to venture beyond the cosy confines of familiarity. Staying in a comfortable state can lead to stagnation and hinder growth. Embracing discomfort and challenging oneself can unlock new levels of creativity and innovation. In art, as in life, stepping outside of our comfort zones can lead to exciting discoveries and transformative experiences.

You couldn’t live without…

Any of my senses, but hearing in particular. Hearing is not only what I use to create and play music, but it’s also how I make a living. Hearing shapes how I interact with the world at large, influencing how the sounds I hear evoke feelings, spark memories or inspire my creativity. In essence, hearing is how I connect with this world.