Text by Ana Prendes

In 2015, the leading thinker and philosopher of science Donna Haraway wrote in Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin, Who and whatever we are, we need to make-with – become-with, compose-with – the earthbound.

Haraway’s pioneering thinking teems with all kinds of different creatures calling for the need of a multispecies earth. Amid an ecological crisis with an unforeseeable end, this symbiotic paradigm has resurged from its niche within the biological sciences in recent years. Deepening into its ecological, social and cultural implications, designers are exploring alternative narratives, asking how intervening in symbiotic relationships might catalyse the emergence of a better understanding of our bio-social relationships.

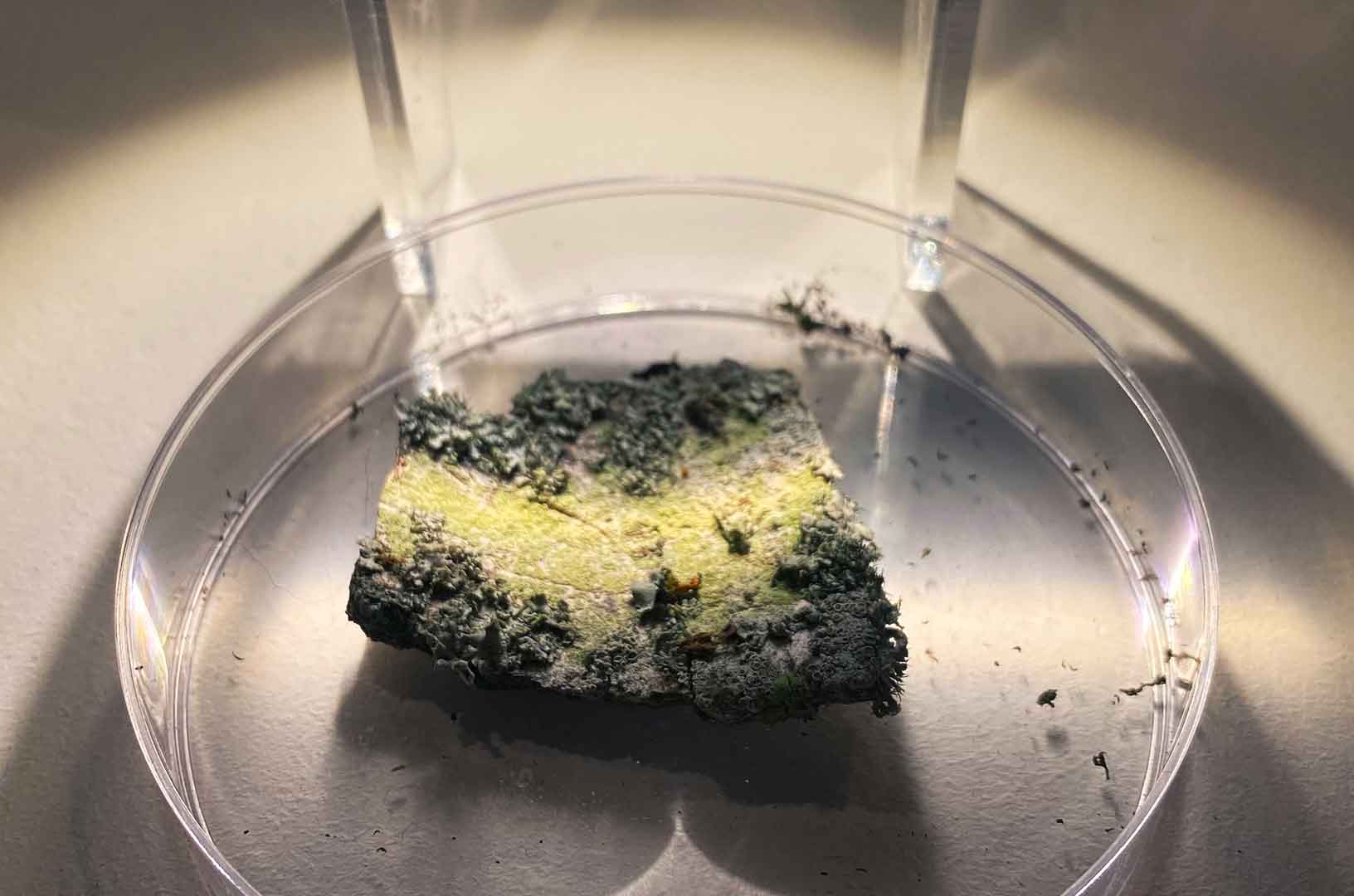

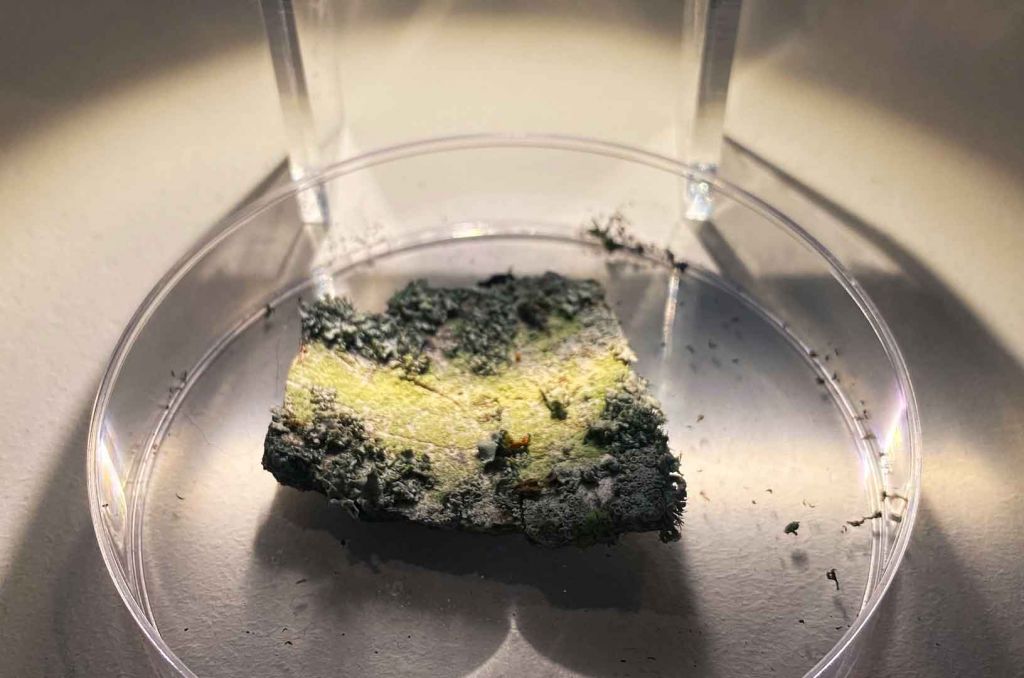

Redefining the concept of ecological service, Habitate is a bioengineered wearable that mimics the ash tree’s bark to support the unassuming organisms’ airborne reproduction that populates their structures.

While studying at the Royal College of Art, designers Yishan Qin, Thomas Hartley and Yuning Chen came across ash dieback. This disease eradicated 80% of the ash tree population in Europe’s temperate climates.

The consequences of this problem affect over 900 species of lichens, fungi, and bryophytes that inhabit their bark. Genetically modified ash trees resistant to this disease may lead to these forests’ repopulation in 50 years. However, their temporary disappearance from these ecosystems will cause the secondary extinction of associated species, which will not survive without ecological networks.

Traditional biodiversity conservation methods usually focus on speciesism, which drives scientific efforts to protect specific organisms due to its familiarity or convenience to humans. This species inequality in scientific research which fails to look at the scale of habitat loss of silent species, encouraged Qin, Hartley and Chen to research temporary spaces for these organisms.

After our investigations, we understood what we needed to do to protect an endangered species from losing habitat and extinction. The key conservation objective is maintaining healthy populations and genetic diversity, which requires a healthy amount of habitats and connectivity between them, Qin, Hartley, and Chen told CLOT.

To better understand the living conditions of these species, the three designers conducted a multispecies ethnographic study in collaboration with an ash tree specialist and a mycologist. The designers identified acidity levels, moisture capacity, texture, and light levels as the key parameters determining these species’ living conditions.

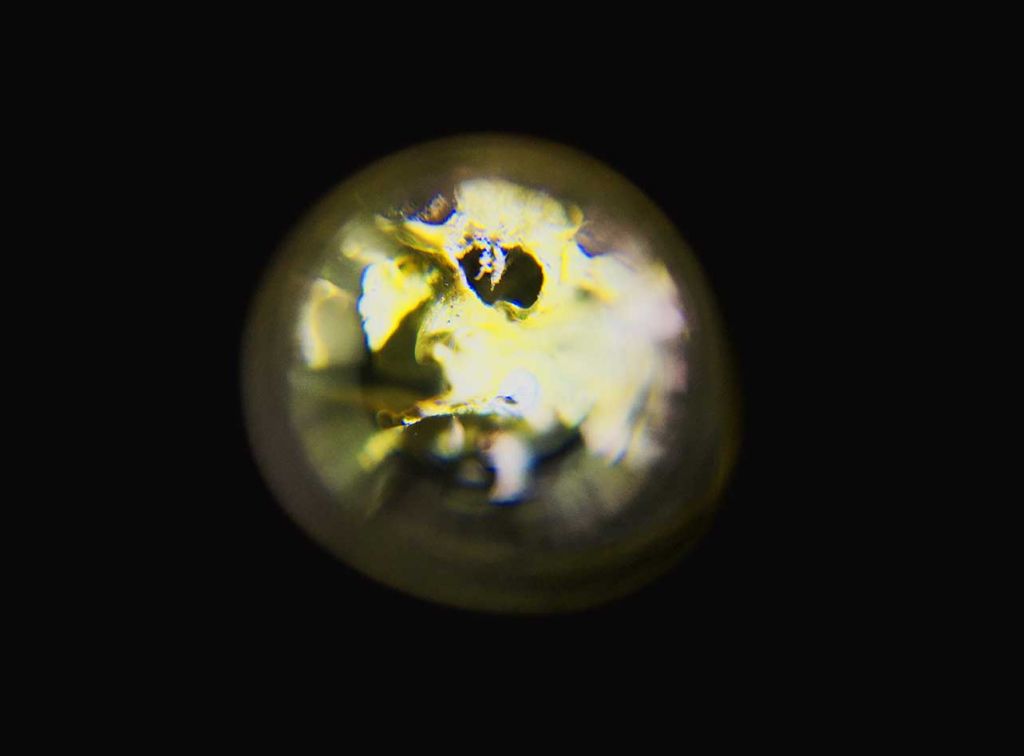

Consisting of a multilayered material, the wearable aims to reproduce the ash tree habitat through biomimicry. A top concentrating lens layer matches the relatively high light intensity that the organisms receive on the bark, which results from the characteristic low canopy density of ash trees

Employing high-resolution thin polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) film patterning, the second structure replicates the bark’s topographic microstructure, which is crucial for cell attachment growth on the wearable. The base material, made of modified plaster, mimics the moisture-holding capacity and the slightly acidic pH level of the bark, enhancing the ability to thrive of the targeted organisms.

During the development process, the designers came across the habitat connectivity for these species to flourish and reproduce. By simulating natural interdependent networks through human social dynamics, Habitate draws on the human as a vehicle of nature. Worn around your arm, the ecological interaction of the species living in Habitate is mediated by human social interaction.

A handshake, a hug, or a conversation facilitates spore dispersal, boosting genetic diversity and population growth. Creating new symbiotic relationships, the designers explore how fusing their habitat with the human body will provide the species with a host which can support their survival.

The varied backgrounds of the designers are reflected in the systematic approach employed for the design of Habitate. Coming from the environmental sciences, Chen pivoted their study towards design. Influenced by kin-centric ecology, cross-species language studies, and object-oriented ontology, she uses discursive design to render different imaginations of how human and nature might coexist together.

Throughout his electronic engineering degree, the technical expertise he learned led Hartley to Innovation Design Engineering to tackle problems at the intersection of design and technology, driven by his excitement for transdisciplinary collaborations.

Qin has a more traditional ‘artistic background’, with a degree in product design and personal practice in UX design and fine art. We found each other because we all wanted to do something to expand our imagination […] We all had a similar level of curiosity, craziness and diverse skill sets to allow us to tackle a project from all angles – rational and emotional.

Design provides the tools to contextualise and understands complex system-scale problems, empowering communities to ideate local solutions to global crises. Habitate mobilises the concept of symbiosis by mapping emerging symbiotic collectives to deepen our understanding of habitat loss’s cascading effects. Inviting people to be temporary hosts and encouraging others to do the same allows us to play an active role in maintaining biodiversity and challenges our limited human-centred perception.

As the three designers remarked, the visible symbol of support for these species is further designed to create a cultural impact in addition to an ecological one. […] It’s critical not just to protect the physical presence of endangered species, but also their cultural and mental presence. […] Increase the sense of relevance and encourage active engagement in species conservation, leading to a better coordinating pattern between human and nature.