Text by Daniela Silva

Gender equality has sparked social and political movements throughout the world. While these social movements for equality are not new, social media is used to fuel them. Because users can spread information rapidly and to a broad, global audience, advocates for equal rights and feminism utilise social media as a forum to raise awareness of continuing concerns and encourage change.

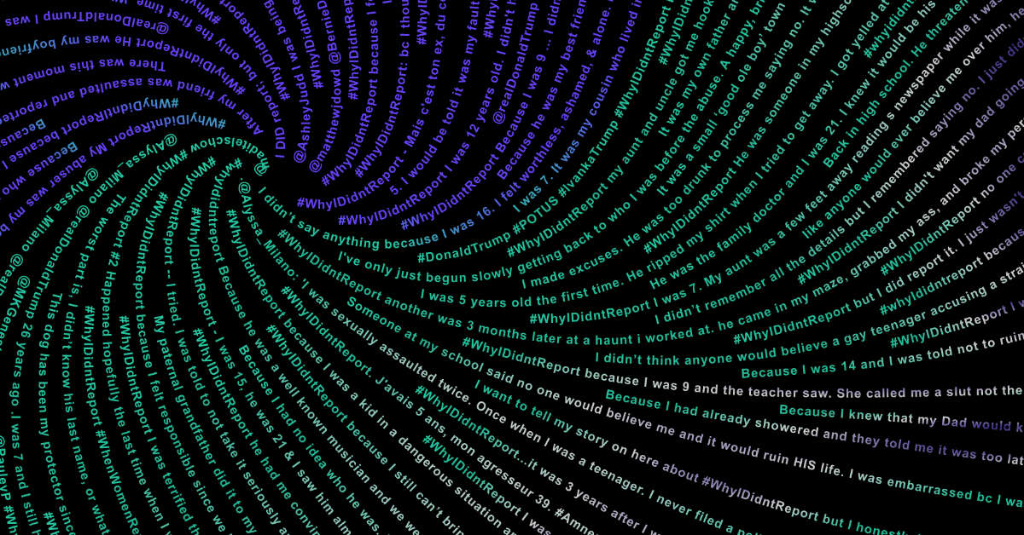

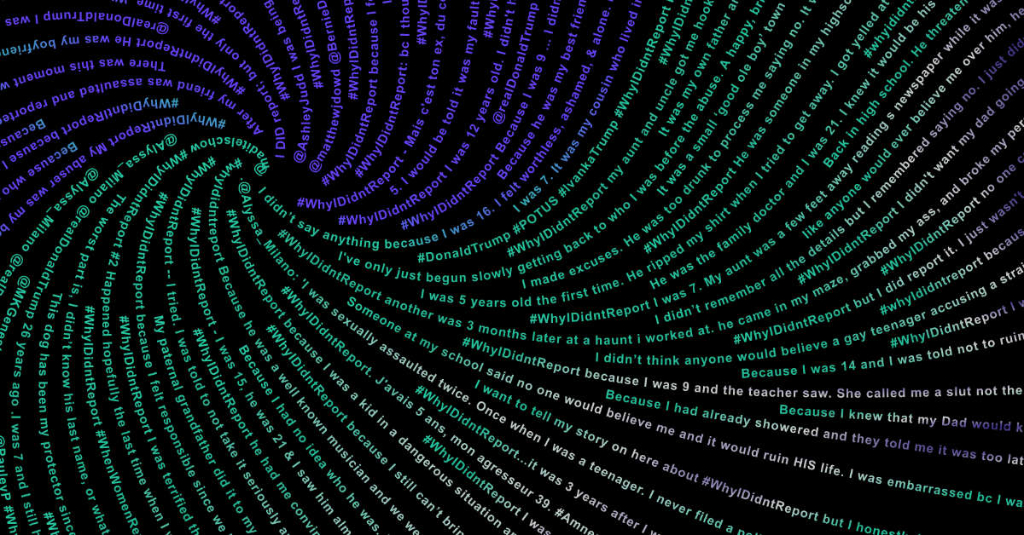

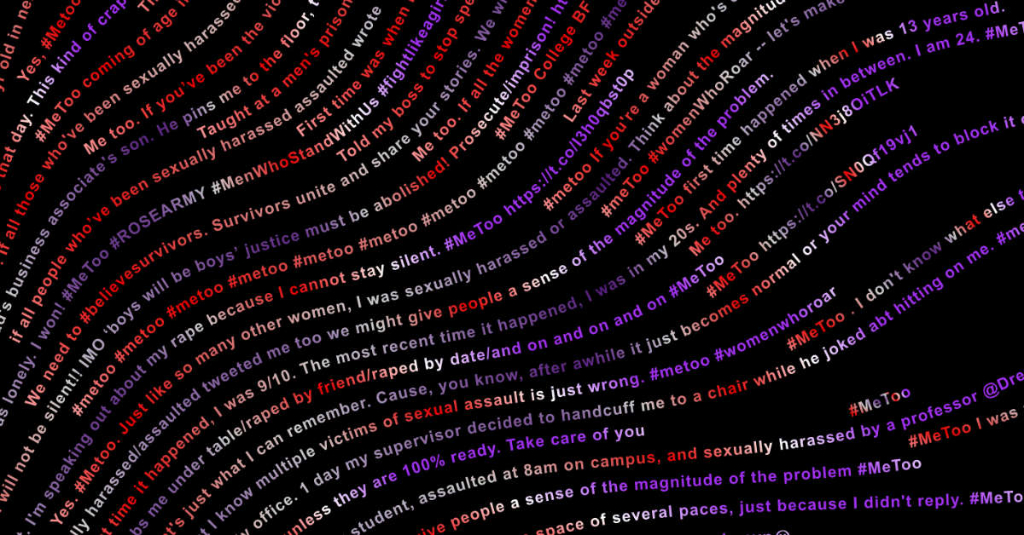

The #MeToo movement spread virally as the hashtag on social media platforms brought attention to the pervasive issue of sexual assault and harassment among women. Focused on the outcomes of this movement, a new project arose, focused on the non-networked, the unliked, never shared, and uncommented.

Over the past year, Kim Albrecht – a visual researcher and information designer, interested in networks, time, power, processes and how we can find visual representations for these topics to produce and represent knowledge – investigated, with the help of Catherine D’Ignazio, Cole Martin, and Matthew Battles, one million tweets related to #MeToo. As a result, they concluded that most networked tweets (liked, commented, re-tweeted) are not representative of the movement.

The highly networked tweets contain questionable veracity, bots, and political content. The actual tweets against sexual harassment and violence, activated by people making public allegations, are in the vast majority not “networked” in the sense of likes, comments, or re-tweets. Nevertheless, they have collected and visualised parts of this unobserved social media section to manifest the otherwise neglected.

The project started in 2017 with the initiative of the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University by collecting tweets with MeToo hashtags. As a result, the Library’s database now has more than 30 million tweets. Later, in 2020 Schlesinger and the Harvard Data Science Initiative invited researchers to study the collection.

Before we, Catherine D’Ignazio, Cole Martin, Matthew Battles, and me, started looking into the data, our idea was to observe tweets about sexual assault and harassment and their development and reflection online. How do these tweets spread throughout social media? How are the people retweeting these tweets? Are the comments positive or negative? Do comments shift in tonality throughout time?

Once I made the first data analysis, we realised that such an analysis would not be feasible. Apart from some celebrity tweets, there are almost no retweets or comments on a vast majority of tweets about sexual assault and harassment – the data rendered very differently from our conceptions. The tweets with many retweets were either spam, bot activity, hate speech, or political commentary, but almost none of the tweets we studied were about sexual assault and harassment. This became the turning point of the project towards analysing the unobserved side of Twitter, the dark matter of social media data, says Kim Albrecht.

As the project evolved, the main challenge emerged: How to analyse the non-quantified? The group started reading these tweets in a team effort to deal with the undefined. A small tool was created that allowed them to read through various tweets, comment on them, and include or exclude them from the datasets they created.

Within the process, Catherine D’Ignazio came up with the idea for one of the final datasets that we visualised: Collecting tweets with no more than six characters, meaning the hashtag MeToo in all its different writing styles: #metoo, #METOO, #MeToo, #Metoo, etc. But rather than seeing this as ›slacktivism‹, something was empowering about these tweets. They resist the compulsion to share details for media consumption and become acts of witness, solidarity, and quiet accusation in their information absence. Even without comments, likes or retweets, these tweets stand together in witness to structural violence that can barely be named, to experiences that are still too close to disclose fully. Of course, ›slacktivism‹ can be a problem, but in the case of #MeToo, the situation is instead algorithmic neglect.

When asked about the biases, misconceptions, and current socio-cultural fabrications that, in his opinion, most urgently demand to be dismantled, Kim Albrecht stated that from a technological standpoint, I am currently thinking about the politics of networks. Nowadays, social networks are self-regulated. For example, on Twitter, anyone can follow anybody else. This openness leads to the power-law distributions described earlier, where very few accounts hold the majority of following while most users are not followed at all. Network restrictions or incentives can change these distributions. I am currently modelling how a network evolves under various circumstances. For example: How would a network grow in which you can only follow 100 individuals or vice versa anyone can only be followed by 100 other accounts? What would happen if your »friendships« on Facebook would not last forever but would start to dissolve over time without interaction? Thus far, the conceptions of social networks are highly simplified concerning human interactions. I am speculating about shifting networks into other directions, creating restrictions, and adding dimensionality to move away from the rich-get-richer paradigm in which power is distributed so unevenly.

Tarana Burke’s purpose when she first launched the MeToo campaign more than a decade ago was to promote “empowerment through empathy” among women of colour who had been sexually abused. Actress Alyssa Milano sought to “give people a sense of the gravity of the situation” when she helped launch the current phase of the movement two years ago. #MeToo has always raised awareness of sexual violence’s prevalence and harmful effects. But the trend isn’t just an online phenomenon; it’s a post-digital one in which the online and offline worlds collide and become difficult to distinguish at times.