Text by Silvia Iacovcich

We have heard it many times from our yoga teachers, holistic doctors, and various unofficial and scientifically tenuous channels. But does music really heal wounds? Bohemians and gong bathers have postulated for decades, asserting that the way to inner and physical vigour lies in the ‘hertz’ – the ultimate tonic for the soul and our protoplasm.

In doing so, they beguiled the mainstream audience: browse on Youtube, and you will find the terms ‘solfeggio’ and ‘flautism’ (magical gamma, beta and theta frequencies supposedly waving you into heedfulness) as conventionally acceptable as Justin Bieber, harvesting millions of viewers per year worldwide.

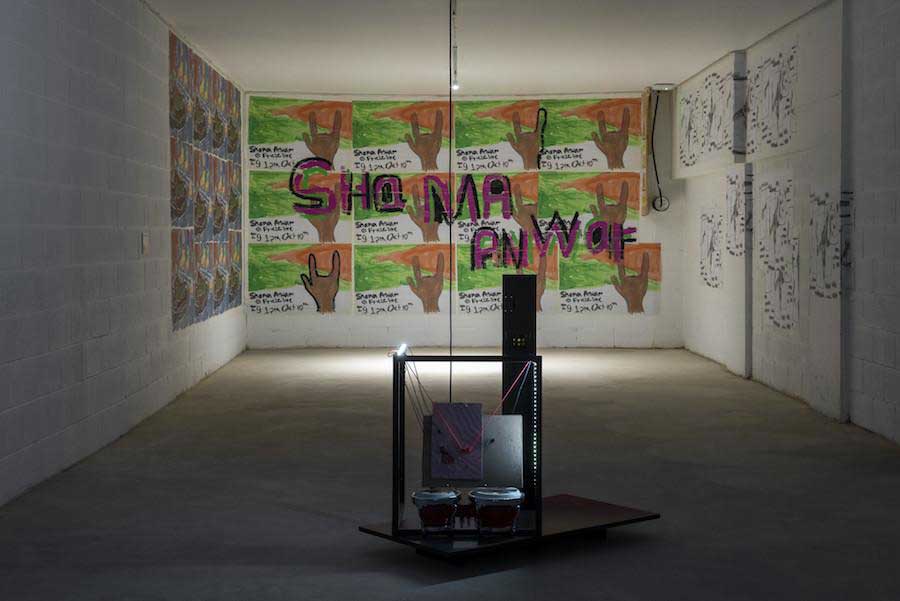

It is not surprising, therefore, that we find symbiotic echos in the terrain of art and sound. A recent exponent was given at Frieze 2020, with Haroon Mirza’s investigations into the psychological properties of the frequencies of 111 Hz, the scientifically ‘certified’ resonant frequency of certain prehistoric megalithic structures that were once hubs for sacred and ‘divine’ rituals. The artist – well known for his wild ventures into sound, light waves and electric currents – designed the Institute Of Melodic Healing with Victor Wang, ‘to promote community and healing by thinking through sound and body support artistic experimental development’.

The extrapolation of 111Hz and its Neolithic associations appears in many sound artists’ ‘expeditions’ – not least Flinton Chalk and Brian Barritt’s 111hz Cairn T Soundtrack, a research project encapsulating a ravishing corollary of sonic vibrations. The video features an archaeo-acoustic soundtrack performed and recorded within Cairn T’s ancient chamber, a monument dating from the 4th millennium BC in County Meath near Dublin – an area dense with Stone Age archaeological finds.

After 10 minutes of listening to the track, the listener is induced into an Alpha trance state. While increasing Theta wave brain activity, it triggers ‘the potential to train the encephalon to stimulate longer-term neuronal activity in the brain’s right-hand hemisphere- producing cell regeneration. We experience strong and defined as if our body was recognising and incorporating these waves.

The Hertz’s fascination comes from imbibing it into a mix of agnostic, scientific and spiritual beliefs. 110 Hz is, for example, used in Buddhist and Hindu chambers; Neolithic stones ‘resonate’ through this ‘holy frequency’ – and stimulate a part of the brain, whose ‘fault’ is often the consequence of mental health conditions which often have genetic components. Releasing endorphins, the frequency induces the expression of the Cytokeratin 16 gene and Keratin 16, which speeds up the wound healing process – or at least acts as a panacea for pain relief.

The English musical trio, Marconi Union’s Weightless, delved into the intrinsic therapeutic properties of music in 2011: through a collaborative project with the British Academy Of Sound Therapy, the eight-minute track was proven to induce a mammoth 65% reduction in overall anxiety, reducing blood pressure and lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

The song is so effective it can make you drowsy – which is why neuroscientists don’t recommend listening while driving, and it’s used instead to calm patients before surgery. In a different direction, Brian Eno’s Quiet Room For Montefiore was conceived to implement sound therapeutics into hospitals directly. His audiovisual immersive installation, built at Montefiore Hospital in 2013, was made exclusively for patients and their families. The aim was to improve their psychological well-being by selecting soundscapes that could work as a functional mood-setting therapy.

Through the experience at Montefiore, Eno opened the doors to a specific branch of ambient music that has been refined during the past years: a disciple of the cause, alchemist and performer Yoko K. Sen has been trying during the past years to alleviate patient’s suffering, through transforming sound design in hospitals – fighting the cacophony of clinic rooms’ invading noises.

The sound artist has been reshaping a new idea of the clinical environment through sonic art: collaborating with Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington. She has been researching how sound can effectively affect and improve a patient’s emotional spectrum beneficial way for the body.

Just as Haroon Mirza adopted a more scientific approach to introduce the concept of healing in sound art, sound artist Torkom Ji is influenced by thousand-year-old healing practices, like gong bath meditation experiences – through a series of vibrations produced by quartz crystal bowls, shruti box and other ritual instruments.

The master sound weaver and electronic musician claims to ‘follow the tradition of Pythagoras and many other sound mystics’, fusing ethereal knowledge with synth techniques to produce a soundscape that can only be described as ‘transcendent’, tuning his sounds to 432 Hz – ‘a pure tone of math fundamental to nature’ that ‘is mathematically consistent with the patterns of the universe’.

Torkom Ji’s soundscapes and the work of many other sound artists like C.Lavender and Jessika Ekomane, seem to be the organic evolution to the pioneering 1983 album Koyaanisqatsi, one of Philip Glass’ most famous scores for the homonym experimental documentary on humanity and its disconnection with nature through technology: the album is still considered one of the best sounds to accompany yoga postures and meditation.

Sound has positive effects on our brains. But what about the rest of the body? Recent studies from Drexel University assert treatment with low-intensity ultrasound could help chronic wounds to heal. It could actually be possible, considering our bodies and cerebral cortex resonate as well, so it would only mean discovering the right frequency for each one of us – which helps the healing process be fast enough to be considered a cure. And just as some claim it heals, conspiracy theorists claim the converse.

The integrated 440Hz has allegedly been used for managing crowds and thought control, replacing the original and more ‘natural’ 435Hz (the one used by Torkom Ji) and 432Hz. Adopted in 1885 by the Italian government as the standardised frequency to tune all instruments in orchestras, to perform concerts homogeneously, 440Hz has felt to many as an unnatural, aggressive frequency conditioning subliminally people into a state of fear, irrationally chosen over the pure mathematical 432Hz – the natural frequency of the universe, being in relationship with the Phi, the Golden Ratio.

Body sound sensitivity – and its state induction through sonic frequencies – was experimented by artist and composer Ben Vida through his multisensory art project, Damaged Particulates. Originally commissioned in 2016 by Unsound Festival NYC, the piece coalesced as a single, through-composed live sound installation that utilized tactile sub-bass speakers that interfaced directly with the audience, transferring low frequencies the body.

Vida claimed that both ‘speech and music could be thought of as ‘particulate’ systems in which a set of discrete elements of little inherent meaning are combined to form structures with a great diversity of meaning’; the cognitive processing of what can be communicated through speech and music is different but communal into the way it structures itself – and it connects with the deepest part of ourselves emotionally and physically.

Sound is and will be a medicine that takes you away and gives you the power to understand the world from a new perspective, a permanent role enduring to our evolution. Tweaking the famous quote from Jimi Hendrix: if something is to be changed in this world – and our body – it can – or might well – only happen through music.