Text by Leoni Fischer

As the grand finale of the exhibition Under the Viral Shadow at Art Laboratory Berlin, the conference held on October 9 brought together the artists presented in the show with scientists from various fields. Curated by Regine Rapp and Christian de Lutz, the program aimed to map out the interlocking research areas of biological and technological networks in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Over the day, the speakers explored multifaceted links to the overarching topic of virality – in the biological, cybernetic and cultural sense. A total of ten lectures were divided into three panels, and the following was rounded up by a keynote lecture by researcher Roberta Buiani. Finally, the event closed with an open debate, drawing again on the links between biological and technical networks, viral metaphors and new technologies’ risks in the “new abnormal” viral reality [1].

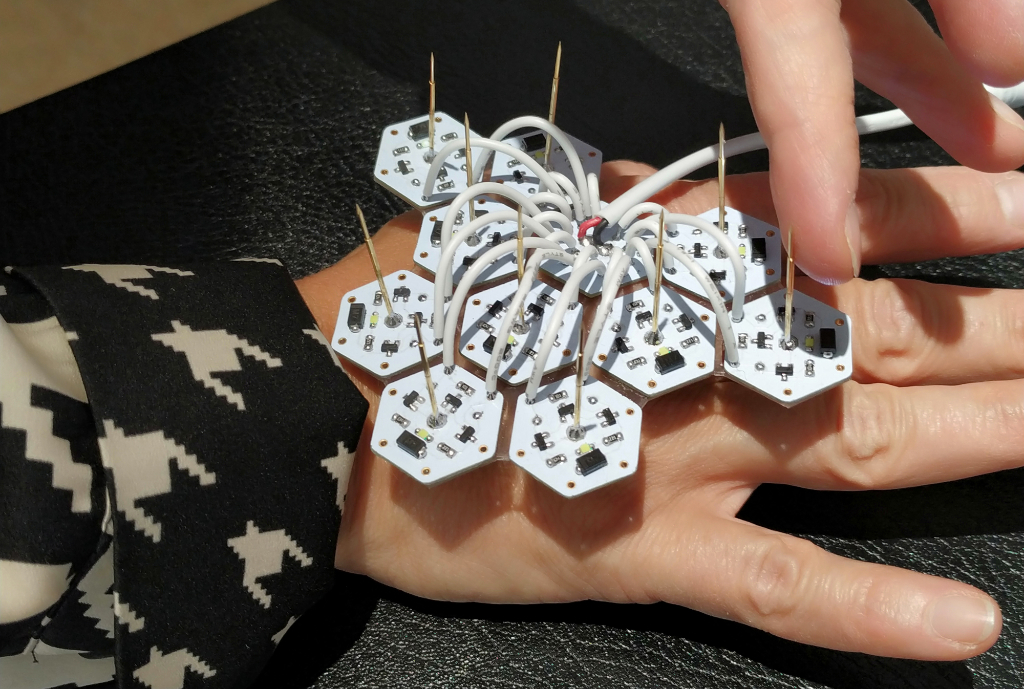

The Chinese interdisciplinary artist, designer, and researcher Vivien Xu started out presenting her Skin Series (2016/2018), two wearables that expand the human perception apparatus differently. Thereby they react to a public sphere that is increasingly permeated by technology imperceptible to the human, questioning if, as our habitat changes with technology, are we prone to change with it as well? Vivien Xu explained.

In the show Under the viral shadow, the aesthetics of Electric Skin appear strikingly virus-like. The orthosis is covered with small red honeycomb-shaped plates with a silver spike protruding from the centre as technological armour. Arched over the wearers’ chest, it resembles well-known SARS-CoV-2 visualisations, making it seem like a perfect match for the conferences’ poster motif. On the other hand, Sonic Skin makes the body’s movement audible in space, thus imitating the sonar system of bats, a species whose mythical image as a sinister creature was sadly reinforced by the pandemic.

But how do physical models change how we understand things that are generally not perceivable to the human senses? For Engineered Antibody, artist Anna Dumitriu worked closely with the scientist Xiang Li. Translating his model of an antibody, extracted from the blood of an HIV-positive patient, into a string of pearls, the artist created a necklace that precisely represents the 21 amino acids making up the antibody. However, an important aspect of the project is the reciprocal benefit of the transdisciplinary collaboration between Li and Dumitriu.

As a result of the physicalisation process, Li encountered a previously unnoticed error in his sequence, which was subsequently rectified. The reflection on art and science collaborations was one of the conferences’ reoccurring focal points. Dumitriu emphasised the importance of informal moments within such collaborations, highlighting how mutual understanding can grow, especially during waiting times between tasks in the lab. Xu also stressed that a radical transdisciplinarity could not do without intensive communication, such as using technical terms within different disciplines.

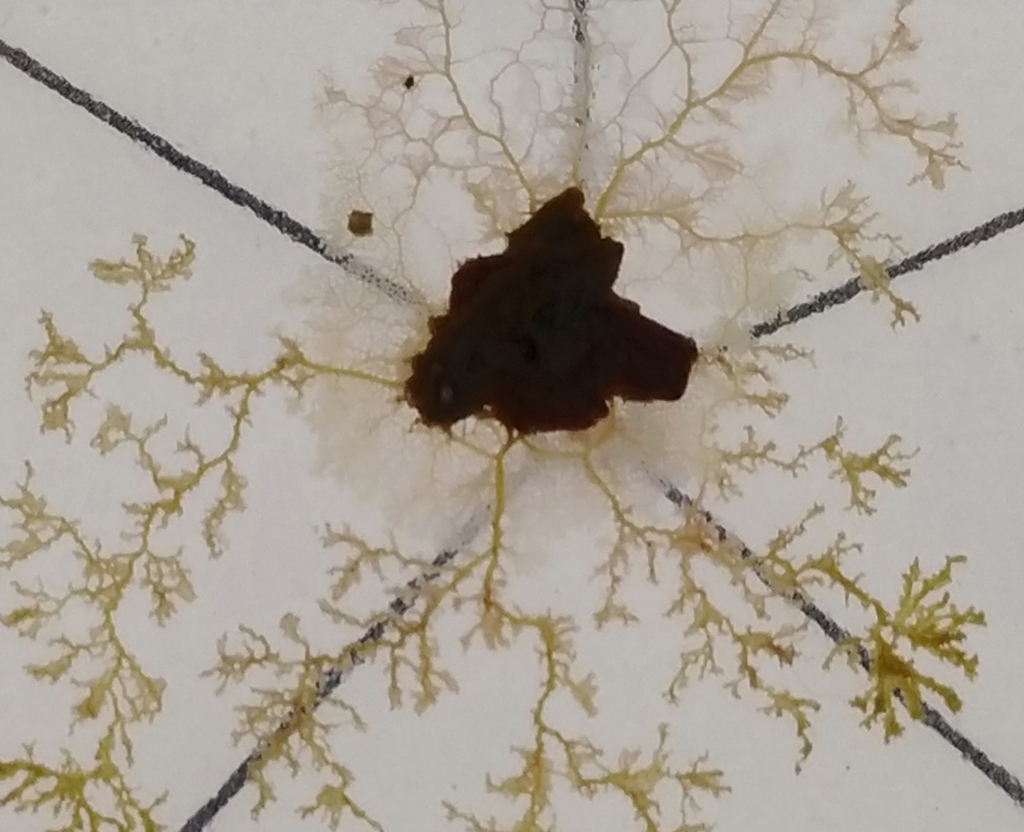

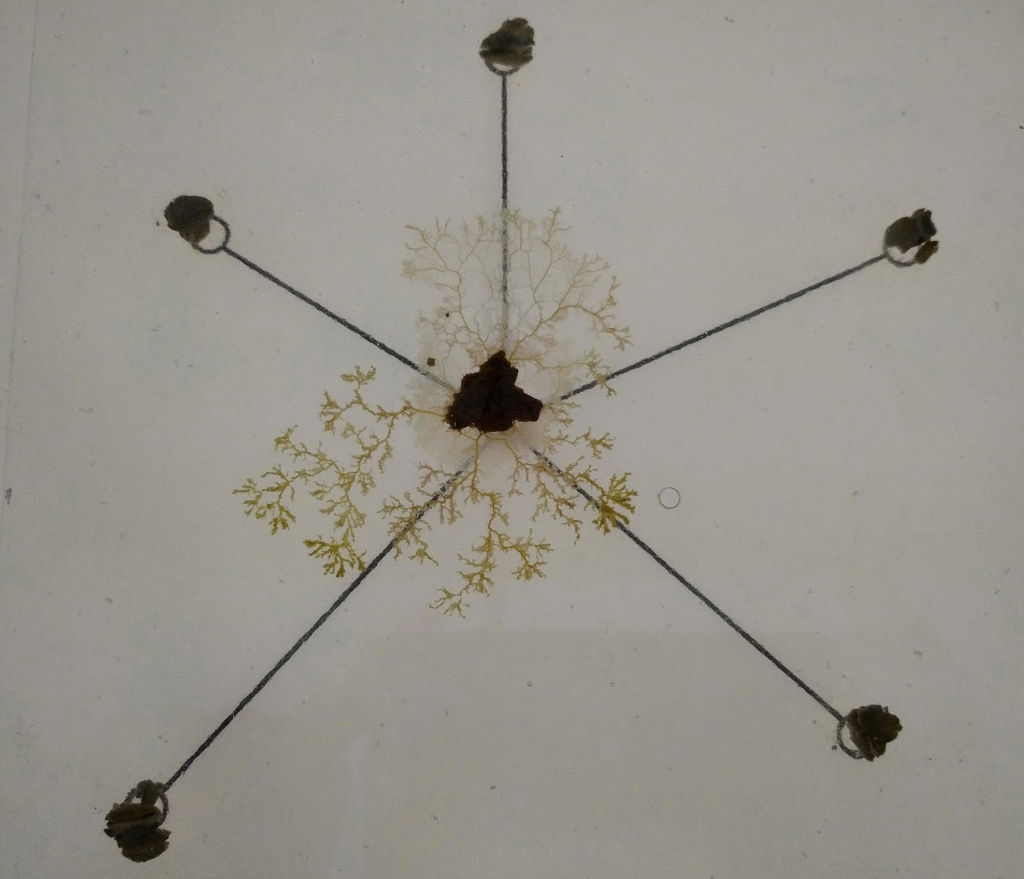

The relationships between organic and digital networks formed the core topic of the second panel. After Sarah Grant’s presentation on her artistic research with Physarum Polycephalum, Dr Christina Oettmeier from the Institute for Biophysics at the University of Bremen further elaborated on how this slime mould can be of interest in the context of network studies.

Although the slime mould is capable of complex behaviour, such as calculating risks, and thus has basic cognition, the scientist believes that ascribing consciousness to it would be premature because of the lack of clear standards for describing consciousness in general. Furthermore, cognitive processes developed independently of one another during evolution.

The slime mould thus “thinks” through “fluid information processing” instead of using a brain. Finally, posing an intriguing thought experiment, Oettmeier drew a direct link to technological networks: could a notebook, on which a person without memories documents every thought, be considered his memory even though it existed outside his body?

Following up on the topic of cybernetic networks, Danja Vasiliev presented various metaphoric misconceptions about the Internet: imagining it as tubes “connecting the world”, as something you can plug yourself into, as a corporate gateway or as a magical alternative reality, the Internet, therefore, is a vital, deeply misunderstood infrastructure on which we increasingly depend, leading to the need to deconstruct such networks to be able to understand them.

So what’s the main difference between biological and technological networks? According to Oettmeier, the embodiedness of organic networks make adaptability the decisive factor over the life and death of the system, whereas a digital system is a purely functional infrastructure. However, this adaptability becomes fatal in adapting the slime mould to the lab environment, where it has been commonly bred for decades. In this clinical sphere, it has lost part of its immunity to bacteria, a development that we see as well in the context of human life, taking place in increasingly sterile environments – consequently making the human organism more susceptible to diseases. At this point of the discussion, the “Viral Shadow” hovers over the conference for a second time.

In her Keynote, Roberta Buiani focused on representing viruses in science, media and culture, providing information about the difficulties in dealing with the complexity of scientific issues. Using various examples from the COVID-19 pandemic, she showed the reality-constituting effect of models, drawing a parallel to the visual representation of computer viruses.

For example, she highlighted the similarities between John Hopkins University’s COVID-19 map and a well-known online visualisation of global cyber attacks. Especially relevant was the connection to the violent history of virus transmissions in the context of colonial history. Presenting Trading series (2004) by artist Ruth Chuthand, she stressed the high price paid by native people in North America for their trade with colonisers who, in return, brought fatal diseases to the continent.

Finally, looking at global politics through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic made the “viral shadow” rise once more since asymmetrical power relations between the global north and south were exacerbated through vaccination protectionism and epidemiological narratives deliberately used by populists to stir up racist resentments.

After artists Benjamin Bacon and Gene Kogan’s presentations using machine learning in their artistic work, Katta Spiel and Alexander König brought two key points to the table.

A researcher at the Technical University of Vienna, Katta Spiel, explores the position of marginalised bodies in human-computer interactions. Their examples from their everyday life experience pointed out how non-binary people are discriminated against through digital interfaces like digital forms, emphasising how data and technology can never be neutral. Alexander König, a researcher at Bauhaus University Weimar, made it unmistakably clear that free research in AI is troubled by the knowledge monopoly held by Google and how artists using artificial intelligence today are always dependent on corporate resources. According to König, the central problem lies in the digital capitalism behind new technologies, leading to a loss of autonomy in research and, consequently, the arts.

As a biological, cybernetic and cultural phenomenon, the virus has become interwoven with our lives’ fabric in ways beyond the metaphoric. But what does this mean for a life in the “age of the virus” (Gray, 2021)?

First, we have become vulnerable through our increased dependence on technology during the pandemic and the fact that our social interactions were suddenly mediated through only a handful of social media portals. As Danja Vasiliev pointed out, being dependent on the Internet, a piece of infrastructure that is so often misunderstood and mystified, can quickly become dangerous.

Second, today, many of our online activities, like our shopping behaviour and even political opinions, are influenced by digital assistants who ever collect more information about us in their databases. In the coming years, our dependence on AI will only increase, while already today, Google alone holds many times more personal data than its’ competitors Apple and Amazon.

This brings us back to the viral since a company has more information. Finally, posing, the more vulnerable it becomes to man-made viruses of the second kind: computer malware. On the biological side, however, the ongoing destruction of wildlife habitats in the service of exponential economic growth will help new viruses mutate, consequently spreading to humans.

At the end of the conference, one can conclude that technology can never be better than the society that creates it. But when capital accumulation drives the social form, it seems like capitalism is the virus. And ultimately, the digital capitalism behind the development of artificial intelligence also endangers the freedom of art. Because if we allow this knowledge to be monopolised, the digital arts will increasingly be deprived of their autonomy.

If you missed the conference, you can watch it at this link.