Interview by Isabella Ampil

Michael Begg is quick to cite his sources. Talking about the wells of inspiration for his work, he credits a stranger on a train, the hills just at the edge of his childhood home, or the fear of finding himself atop a crane for the first time. He has a keen sense of the richness of the world, and his music seems to hold all the sounds of daily life that lurk just beneath the surface, which may appear to the rest of us should we pay close enough attention.

Begg grew up near the Pentland hills in Scotland, where he started experimenting with music with his friend Deryk Thomas in the 1980s. In the 90s, while attending the Chelsea School of Art in London, he worked on writing, theatre, and music outside of class, developing his talents in these areas that he continues to hold close to him.

His articles for Sound on Sound and his compositions for Moscow’s blackSKYwhite theatre company reflect his work from that decade, particularly with Russian and Polish theatre (which Begg describes as more physical and less narrative than Scottish theatre).

He reunited with Thomas in 2000, cementing their collaboration with a record deal under the name Human Greed. Since then, Begg and Thomas have released nine albums as a duo, the most recent of which is 2016’s Let the Cold Stove Sing, described by experimental music review site A Closer Listen as “moody, introspective and gravitational.”

At the moment, Begg is fresh off of a sound installation called Ghost Conference, hosted at the Bunkier Sztuki Gallery in Krakow, Poland, which suggests those same roots in Polish theatre in the 90s. Ghost Conference, created by Italian composer Lorenzo Brusci alongside Paweł Krzaczkowski and Marcin Barski, offered layers of manipulated sound – live guests with streamed voices in some parts of the room, providing expertise on academic subjects, as well as original music. Begg contributed a piece of music accompanied by spoken text that highlighted the work of John Berger, author of A Seventh Man, a 1975 book documenting the lives of migrant workers in Europe.

For connecting him with the CMMAS program, Begg credits Cryptic, an art house in Glasgow that aims to collect the best contemporary multimedia art. Cryptic puts on Sonica, an international showcase of sonic art that pops up in Glasgow every two years as an eleven-day festival but has toured worldwide since its establishment in 2012.

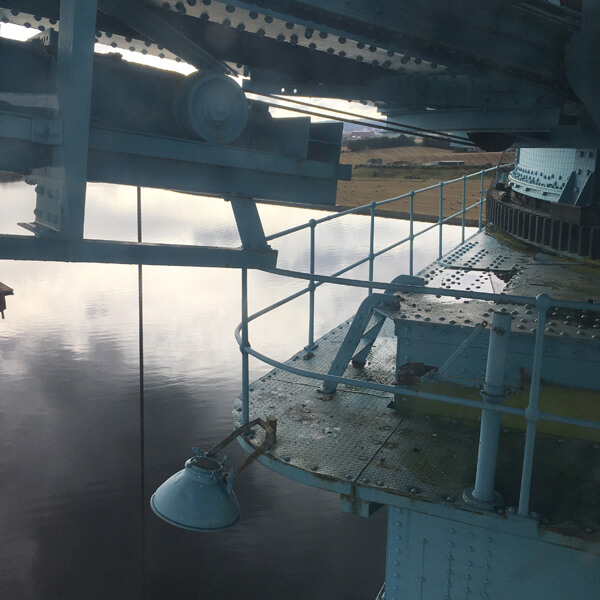

For Sonica 2017, Begg created TITAN: A Crane Is a Bridge. The work is a homage to site-specificity, using additional strings and cables to capture the eerie gusts of wind in deeply moving, harmonious phrases. Visitors to TITAN have praised the piece, which won the New Music Scotland 2018 Award for New Electroacoustic/Sound Art Work, for its ability to capture the thrill of the crane.

The purely physical dread of its extreme height and the fear, innovation, and nostalgia of industry that it represents. Yet listening to the sounds on their own, many miles from TITAN and months removed from Sonica 2017, one feels the same slow, churning sense of connection with the world, ebbing and growing, that dissipates once the album ends but lingers long in the memory.

You are a composer and musician based in Scotland. For those that are not familiar with your work, could you tell us about your background and aims as a composer and musician?

I was born in Edinburgh and raised outside of the city in a village on the edge of the Pentland hills. The proximity of the hills, the unusual safety and comfort of the nighttime hours, the immediate environment of neat, new build houses serving war baby parents and their incomparable optimism, the closed paper mills bordering the river, the dead train line leading back down to the city. I am formed of these things.

I still find it hard to talk about the work because that is the job of the work. I have been releasing records since 2001. Initially computer-based and almost entirely textural, there have always been these two competing poles of abrasive atonality and melodic sensitivity that I like to rub against each other. Whilst I work with a broader palette of instruments now and am often lucky enough to work with other incredible musicians, I am still very much bound to the processes of the studio, the studio as an instrument, to resolve and realise my work.

I have released several records with Deryk Thomas under the name Human Greed and am deeply and proudly involved in Clodagh Simond’s Fovea Hex. In the last five or six years, I have released several solo albums which are increasingly related to installations and other commissions from the likes of Cryptic, Artichoke, and National Galleries Scotland. My music is located in the place where formal composition and electronic erosion meet, a liminal space coloured by longing and discomfort.

My sense is that at the point where the recording was invented late in the 19th century, there came about a divorce between music and its place, its context of delivery. Technology drove music-making into dry, sterile studio environments where all extraneous artefacts and imperfections could be snuffed out. But this same technology opened the doors to new disciplines and forms when used outside of the studio, and which had little to do with music; field recording, ambient, acoustic ecology, the articulation of the soundscape, and so on.

In the same way that cinema plays really interesting games with diegetic and non-diegetic sound, I like to explore the emotional potential of introducing this contextual, often foley-like content into studio recordings. To my ear, it sharpens an edge that decades of studio sterility have blunted in the experience of listening to or experiencing music.

My feeling is that it makes listening to a much more attentive act if you are engaged in determining what is the music is and what the additional content—or having to consider if you are listening directly to the music or if you are listening to music that has been played and realised somewhere else and that you are listening to a recording of an event in time rather than a piece of music.

That’s a long and possibly overwrought and tedious way of explaining that I am caught up with the relationship with music, sound and place. Another side of what I am dealing with can perhaps be offered by this brief story. I was on the last train back out to East Lothian one night. It was 11 pm. There was a man sitting opposite me.

He had been drinking and was pretty drunk. But he had his headphones on and was listening to something good that he was really, really into. His fingers were picking out the full range of the rhythm, and his head turned once in a while as though he were keeping an ear forward to catch the detail. I watched the expression on his face change from absolute joy to abject pain and from a sort of zen blank serenity to an all-consuming rictus of expectation.

There were tears coming down his cheeks. I suddenly had this clear, albeit fleeting, sense that this man was being dissolved by music. There was more of him – his identity, his body, his mind, his memory – occupying the music he was listening to than occupied the train carriage. I was effectively looking at his husk. He was elsewhere.

His experience of music was akin to time and space travel and was genuinely transcendent. I’m not saying that I have ever reached the heights of being able to produce a work capable of such things. That will never happen. But that’s the yardstick. That’s the sense of what we’re dealing with.

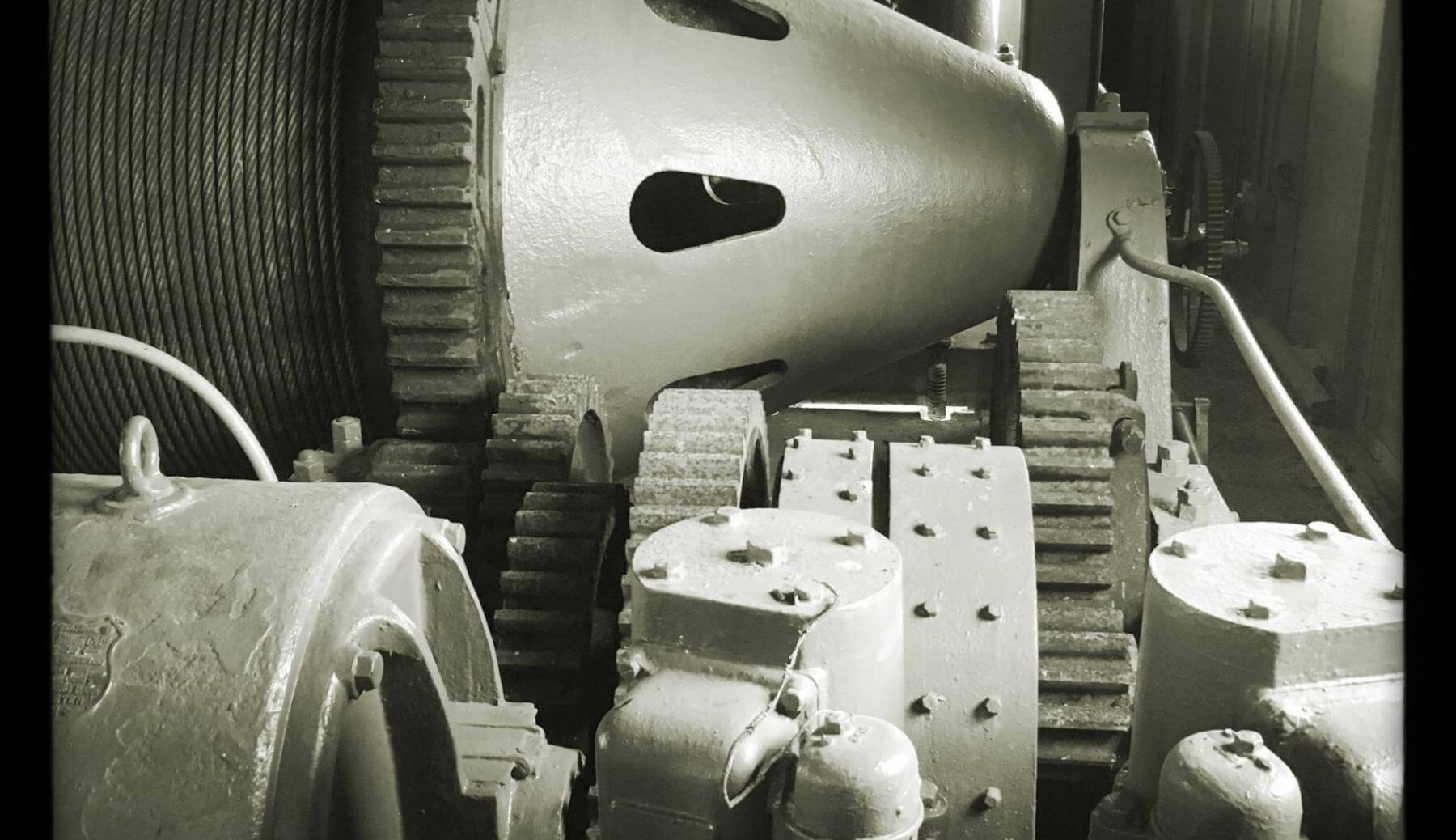

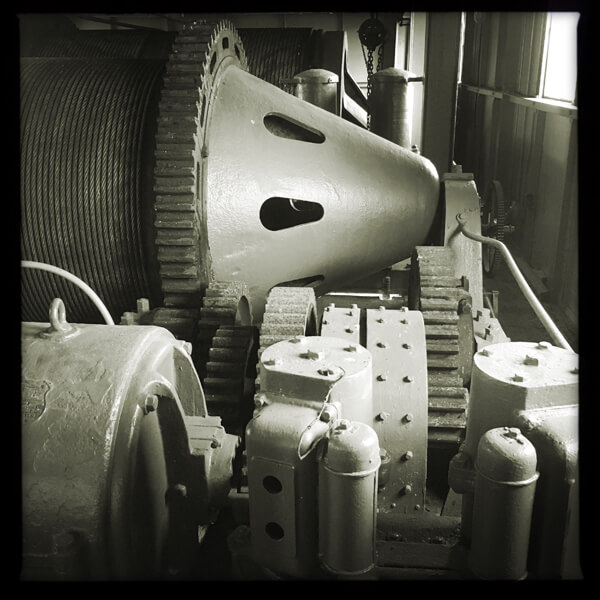

Your last project TITAN was commissioned by Cryptic Glasgow for the 2017 Sonica Festival. The requirement was for a site-responsive electronic work to be situated in the wheelhouse of the Titan Crane, 150 ft above the river Clyde in an abandoned Clydebank shipyard. What was the intellectual process behind its inception?

There was an open viewing of the site that Cryptic had organised before the project began. It is very rare that work unfolds this way, but when we arrived at the top of the crane and I stepped out onto the viewing platform for the first time, a few things happened in succession and in good order. The first thing was that in the sound of the wind whipping through the cables and ironwork, I recognised a resonance with my own acute sense of anxiety.

Very suddenly, just because this anxiety had been located and made apparent to me, the anxiety somehow dissipated. I suddenly felt calm, clean, and strong. So right from that moment, I knew I wanted to do something that would offer visitors to the site the same opportunity to gain something positive and gentle from the most uncompromising materials.

I then also understood pretty quickly that it would be pointless trying to impose a piece of music upon a structure like this. What I needed to do was find some way of getting this incredible structure to reveal its own voice and engage with it that way, as a collaboration, if you like. I spent the best part of the summer up there, alone, capturing the sounds of the crane itself using a range of microphones/contacts/hydrophones.

In the past, I had been very moved by a work of Jacob Kirkegaard called 4 Rooms and had been looking for a suitable project to try out the technique of recording an enclosed space, then feeding back the recording into the space whilst simultaneously continuing to record the same space. This comes from Alvin Lucier, of course, but there was something powerful about the political aspect of Kirkegaard’s use of the technique that really appealed. So I tried this method with the wheelhouse, with some degree of success.

Back in the studio, I would pick through all of the raw recordings and subject them to various processes and treatments, waiting for those eureka moments when something musical would appear from the soup. The great thing with well-engineered structures is that there is a kind of material harmony that runs through the construction. I think architects are slowly coming to realise this and are spending a lot more time considering the acoustics of space.

But for me, for Titan, it meant that I could come to predict what musical key the structure was built in. That made it easier for me to produce melodic elements that could fold into the voice of the crane and still remain true to the structure. There was one moment up there when an engineer told me about the importance of triangles to the strength of the cantilever form, and as soon as he said it, I was thinking – triad!

The work ran for two full days in the Sonica Festival, and I cannot begin to tell you how beautiful it felt to go up there to see how things were going and find people lying flat out on their backs in this most inhospitable space, just taking it all in, and often being clearly moved. The crane, I think, enjoyed the attention too. Titan won the New Music Scotland 2018 Holiday Inn Theatreland Award for New Electroacoustic Sound Art work in March.

What were the most significant challenges you faced in its development? We are curious about the development of the Aeolian harps.

The whole thing was a leap of faith from beginning to end. I had never undertaken a project that was anything like it. Nor had I previously worked up a quadraphonic mix – which is what I constructed for the installation. None of us had any idea what it would sound like in a metal room crowded with huge drums and cables, with the wind screaming most of the time.

The Aeolian harps came about because I needed to find a solution to turn the sound of the wind – which is a near constant up there – into musical information that would give additional dynamism to the installation. I had heard of these harps previously as window harps and understood that folk would place them by an open window to make ghostly, fluid music.

I started experimenting at home. First, with a shoebox, some rubber bands, and a couple of pencils for bridges. I placed it by an open door and was initially dismayed by the lack of sound. But when I attached contact mics to the box, suddenly, there was all this swirling, moaning, diaphanous sound. it was really beautiful. So I worked up from there, making bigger and bigger harps, and trying out different woods, different strings, etc, until I ended up with these three 6’ tall monoliths – which I called Keren, Sarah and Siobhan. Each one was constructed from a length of pre-fab drain pipe.

Each of the four sides was fitted with violin bridges to top and bottom, with 4 strings made from medium/heavy gauge fishing lines (the shark line was too thick and didn’t resonate. Anything lighter just snapped) and tuned around zither tuning pins. That gave a total of 48 strings with the potential to pick up wind. The three harps were fitted with pick-ups which fed back into the wheelhouse and into the mix. Although if you were out on the viewing platform looking down on the river, you’d have the full acoustic impact of the harps.

I never knew, right up to the last minute, whether they would work or not. Or whether there would be enough wind to make them sing. And on the first day, the wind was too strong for them, and they made very little noise. That was a surprise. I guess the wind needed to be gentle enough to allow the string actually to vibrate rather than just be pushed to one side and held there. On the second day, they sang just beautifully. There was a gentle autumnal wind, and the day was bright, with clear skies. That was a very happy moment.

Being based in Scotland, are natural and industrial landscapes and related phenomena a source of inspiration for your compositions?

It has always been there, but never really explicitly so – but it is becoming more so now. And I mean landscape, predominantly. I’ve been living in rural east Lothian for about 15 years now, and as well as being a direct influence on the work and how my days are paced, it has also, I think, contributed to my uncovering just how deep in my marrow the impact of the Pentland Hills has been upon my sense of self.

I recall many years ago working with the Gaelic theatre company Tosg on Skye, and being taken by the way their language grew fuzzy around delineating differences between the people and the land on which they lived. A word like ‘tuath’, for instance, which commonly now means north, once had a stronger meaning comprising a combination of land and people. I am now feeling that biological connection stronger than I used to. I spend a lot of time at the moment driving around the south of the city to go back to the Pentlands.

Not so much as a salmon swimming back upstream, but still looking for clues, answers, maybe even God. This will seem strange, but I sometimes feel that what I am looking for is simply to dissolve up there, under the shadow of the Black Hill. Just dissolve. Become a breeze laced with sheep shit, skirting the shoulder of Scald Law.

You know, it’s funny, but I have been observing the growing popularity of musicians working in some form of rural context or other, and I had been trying to figure out why I was finding it so disagreeable. Then it struck me recently – it’s a form of colonial expression. These are mostly urban artists, and they tend to come out here albeit with the best intentions – but end up projecting not so much the voice of the landscape but a projection of the landscape’s effect upon them.

In itself, this is fine, but when they offer their work in terms of its authenticity to rural experience or present vague politically charged agendas that misread the relationship between the urban and the rural, it becomes colonial, a projection of an alien sensibility upon a place.

You say this project has become a key point of your compositional approach and will inform an upcoming residency in CMMAS, Mexico. Could you tell us a bit more about this residency and what directions you see taking your work into?

The recognition that Titan enjoyed certainly helped assure me that my aim was true. The residency invitation came about because of the incredible support that Cryptic gave – and continues to give – my work. They really are extraordinary outfits. They proposed residency with CMMAS in Morelia as part of the British Council-supported Seeing Hearing UK Mexico partnership.

I met with their Artistic Director in London a couple of weeks ago, so the plans are evolving – but the details are still somewhat up in the air. I’ll be there no matter what, but the availability of others may impact how I spend the bulk of the time. I’ll be doing a solo show at the Visiones Sonoras Festival while I’m there. I had hoped to be able to work with a Brazilian cellist based in Mexico City who has been doing some exciting things with a 5-string electric cello with 5 separate signal outputs.

I still think we have so much ground to cover regarding making electronic and acoustic instruments work together, so this would be a great opportunity to try and make some advances with that. Unfortunately, we now know that she’s working elsewhere when I will be in the country – but there is a lot of enthusiasm for taking this forward, so hopefully, we’ll get to look at that in the near future.

Before Titan, I had completed a work for the National Galleries of Scotland called A Moon That Lights Itself. That was another site-responsive work – but the site, rather than being physical, was manifest only in a series of mid-late 19th century paintings. I worked with a cellist for that, and we just scratched the surface about how to really have fun with combining the cello and the computer.

As regards to where the work is going generally, I am in a curious position right now. There is no shortage of ideas, but nothing is taking the lead. I feel like I am floating on this sea of bright sparks. I could do this. I should do that – so I end up staring into space. The award gave me a short-lived ego boost, but I began to experience bizarre side effects that were debilitating.

Because I have now been called an ‘award-winning composer’, I somehow felt I had to act up to my preconceived idea of how an award-winning composer should behave. You know, compared to an experimental musician, which I had previously identified as. Loosely. And so I found myself trying to write out scores in pencil and consider counterpoint when I have absolutely no gift for that kind of craft.

So, I have rinsed myself and am retreating back into myself. My scores take the form of watercolours and diagrams, and handwritten notes. I stick my head inside the piano to feel the layers of harmony. I build software instruments out of wine glasses, wood-burning stoves, and broken autoharps played with an e-bow. I go out on the hills or into a building, and I make recordings there and begin the process of finding their unique voice. I build up blocks of sound and begin to chip away at them since composition is a reductive process. I liken it to building an arch. Begin with an armature, of course, wooden blocks, around which you lay your dress stones. Once the keystone is in place, you knock away the armature and are left- theoretically – with an arch.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I don’t like the word creativity, and I would always seek to avoid using it. Creativity is for people looking for an activity to make themselves feel good about doing something or making something. Like a hobby, a light distraction. What I am involved in is deeply reflective and consuming and comes with no guarantee of success in any shape or form. This is how I live, and it is only this way through being unable or unwilling to engage with life in any other way. And I am not alone in that. It’s not elitist, and it’s not a whine of complaint. It’s just the way it is.

But you never really hear much about people engaging to that degree anymore. Culture, consequently, suffers because the nature and value and contribution of good, serious, fucked up, neurotic, self-important and self-absorbed art is not viewed as being of value. Meanwhile, the grinning promotion of everybody exploring their creativity in a playful, recreational way fits in very well with the ongoing marginalisation of the arts in the UK.

In schools, music, drama, literature, and painting are all being crushed and obliterated. Creativity, in this sense, is the enemy. Its currency has become completely devalued. Real culture is the victim. It should really be clear at this point that civilisations cannot survive without embracing artistic inquiry. All you have to do is turn on a T.V. to observe that by this reckoning, this particular civilisation is lost.

You couldn’t live without…

Someone asked me the other day if I was superstitious. I said no and threw salt over my left shoulder. Then thought about all of the items that I have gathered about myself that I carry with me habitually and which are loaded with personal significance; my wedding ring, a Claddagh ring from Galway, and another ring from Athens, a string of Greek komboloi prayer beads, a cheap leather wrist strap hooked with a gold anchor symbolising hope (I like to be near anchors), a neck chain featuring the three bees of Heraklion, an art deco St Christopher keyring for my door key, a Moleskine notebook, a black Elysée pen with which Paul Bowles signed my copy of The Spiders House in Tangier, a faded sticker permitting me to take photographs in the salt mines outside of Krakow.

Of course, it would be possible to live without any of these things. We adapt to loss all the time, but we seek our pleasures and our memory triggers and our talismans wherever we can. I have no idea what I am trying to say to you. It’s a strange question to close with.