Words by Diana Cano Bordajandi

In recent years artistic experimentation in music has been gaining more exposure to larger audiences. This results in unorthodox compositions that depart from conventional norms and push the traditional boundaries of music. Serge Vuille, a Swiss freelance percussionist and composer, is an expert on this subject.

Vuille, who lectures in musical experimentation at the Royal College of Music, founded the contemporary music company We Spoke in 2008 and currently directs the Kammer Klang series at Cafe Oto in London. The series consists of live events that explore innovative ways of creating and delivering musical pieces while attempting to connect performers and creators across disciplines.

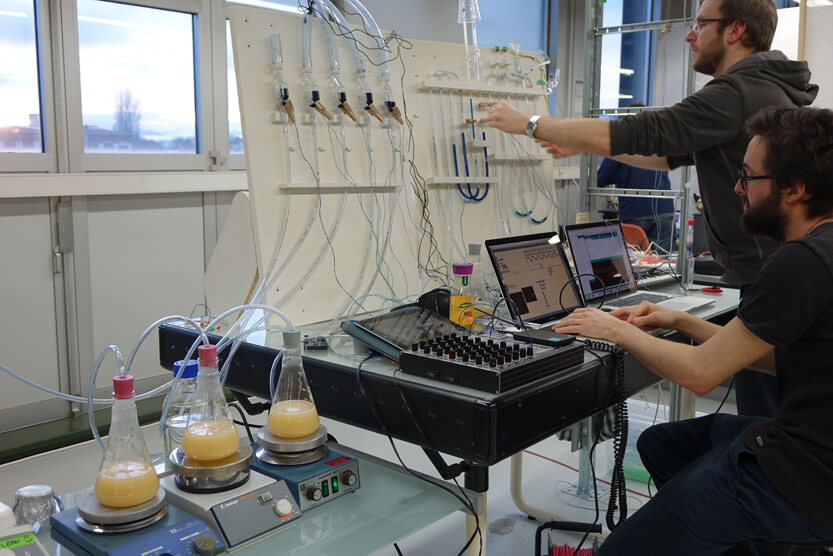

The project Living Instruments – born under the umbrella of We Spoke and the Do-It-Yourself biology community of the Hackuarium laboratory – was recently displayed as part of the Kammer Klang series. The idea behind the project was to build a set of instruments that use biological information as signals that can be converted into sound.

The musical instruments are based on living microorganisms, plants and minerals. They include a “bubble organ” set in motion by fermenting yeast cultures and a “moss carpet” that can be stimulated through physical contact.

The activity that the organisms generate is detected by sensors, recorded as collated data and converted into sound through synthesisers. Essentially, by stimulating the living instruments with pressure, movement and heat, semi-improvised live performances can be delivered by scientists and musicians.

The multidisciplinary team responsible for bringing this fascinating project to life was brought together by Vuille and includes various We Spoke musicians, as well as the biologist Luc Henry, the audio designer Robert Torche, the electronics specialist Oliver Keller and the product and media designer Vanesa Lorenzo. Together, they have created something brilliantly unique, merging music and biology.

By demonstrating that biological processes can be used to create musical pieces, Living Instruments exposes a connection between the arts and sciences and makes us think about the role of music in living organisms.

For those who are not familiar with your project, Living Instruments is a live performance using micro- and other organisms to generate sound. Could you tell us the intellectual process behind the inception of Living Instruments? How and when the interest in mixing sound and living systems (or other natural world systems) came about?

LH: The Living Instruments project was born in the autumn of 2015 when Serge Vuille paid a visit to Hackuarium. We knew each other from childhood, but it was the first time he visited our community laboratory in Switzerland, and he immediately suggested we should do something at the interface between music and the Do-It-Yourself biology we want to promote at Hackuarium. Very quickly, we had a team interested in building instruments that were based on living microorganisms. The result is what happens when a musician, a biologist, an electronics expert, an interactive designer and an audio designer get together.

SV: There are two aspects to the project. The first one is to use natural processes and living organisms to introduce an organic feel to the music. We interact with microorganisms, plants and minerals but cannot control their behaviour completely. We can observe or stimulate them, but ultimately, their natural reaction will define the output. Most of the sounds are generated using computers or electronics, but unlike most human-computer interactions, this living layer means we can only have ‘soft control’ over what is happening.

The second aspect is about how we interact with life. Some of the instruments are very passive, in observation mode, while others allow controlling the microorganisms and ‘forcing’ them to move in one direction or the other. It can feel a little uncomfortable at times. We would like our audience to have an emotional response to these various types of interaction too.

Living Instruments is an interdisciplinary and multifaceted project, with different people developing different instruments. What were the biggest challenges you faced in its development?

SV: The project developed very organically around the different skills present in the Hackuarium community. Musicians from We Spoke joined one by one, and the project grew naturally. Dealing with very tight timelines is the biggest challenge for the team. We worked over three months towards the first performance.

On the one hand, this may seem like a really long time for musicians to work on one project. On the other hand, developing completely new instruments from scratch is extremely short, with complex sensors, microcontrollers and synthesisers communicating with music software.

LH: Because we all normally work in different contexts, with their own rules and codes, it is difficult to understand how others think, what they expect and how we can bring complementary aspects to the final result. We are still unaware of some of the technical details others master, and we are learning from each other each time we meet to perform or to develop the project further. Also, because we live in different places, logistics can be a challenge.

What direction do you see taking the project or idea behind living instruments into?

SV: We are currently working towards a longer version of the piece, about one hour. It will include a ‘documentary’ introduction, looking into how the instruments were built, background information on the organisms we’re using and on team members too.

We’re also rethinking the piece in terms of musical composition, developing sounds that relate to the concept, and allowing for interesting combinations between instruments. We’re learning to improvise on stage, really using the devices as ‘musical instruments’, and fine-tuning the use of live video on stage too.

LH: We also want to keep the project open, allowing to include more people, more technologies, and more ideas in the future. While we do want to have a more stable, controlled version to be performed, Living Instruments should also keep a work-in-progress dimension, potentially including new discoveries and ideas in the future.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

LH: Uniformity is killing creativity. As a scientist, I find it radically refreshing to work with individuals who have a completely different background education, come from a different culture, and who can question things and bring new ideas to the table. Living Instruments would be a completely different project if it were just me and a group of biologists trying to make music.

SV: I think creativity and the arts need urgency and time in equal measure. If the situation is too comfortable, one might not explore ideas as far as one could. On the other hand, the brain needs time to refresh, and I think periods of apparent inactivity are important too. The enemies could be both uninterrupted comfort and uninterrupted stress.

You couldn’t live without…

SV: Learning something radically new every day. I think I’m a generalist. I prefer to know a little bit about everything than everything about a little bit. In this sense, I always need new fields to explore and new directions to test.

LH: A place filled with curious people where I am free to experiment outside my comfort zone and learn from everyone. That is why I initially founded Hackuarium, and even if technical skills are crucial to making things, the arts often bring a purpose or a critical dimension to what we can achieve with technology.