Text by Allan Gardner

I want to begin with a caveat – I have been to Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s Earwitness Theatre at Chisenhale Gallery once. I attended the opening, an incredibly busy opening, and this was the context in which I experienced the work. For this reason, I’m going to be focusing almost entirely on Saydnaya (the missing 19db) (2017) because this is the only piece with which I really had an experience on that opening night.

I suppose it might be worth highlighting that an opening is rarely the best time to experience a work, and nearly a month after the fact is rarely the best time to write about a work, but in this context, I think it speaks to the quality of the piece.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan and Forensics Architecture have been receiving a great deal of press, a great deal of conversations surrounding whether it really is art at all and exactly where the line is between political research -also with a heavy reliance on the most advanced technologies- and artistic practice, [1]. This piece of writing is my assertion that, within Earwitness Theatre, Saydnaya is irrevocably an arresting piece of art. The kind of artwork that burrows into your mind and has you talking about it consistently for weeks.

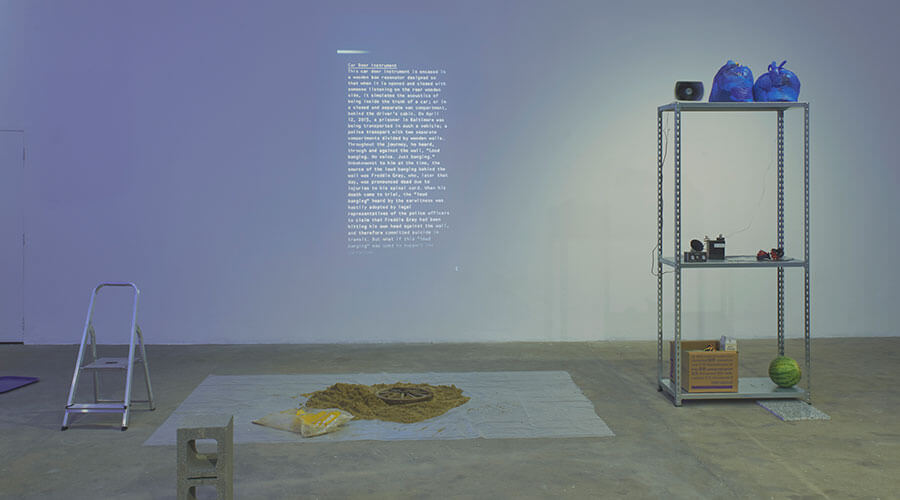

Entering the main room at Chisenhale, there is a collection of objects to the right side and a projection on the far right wall. On the left of the room, there is what appears to be a sort of hut, with a gallery assistant escorting viewers in and out. I stumbled briefly past a popcorn machine, soda bottles and assorted detritus before approaching the hut and being led in just as the audio piece began to play.

I sit on the floor with around fifteen others; two speakers pointed at us. There’s something about having these so visible, especially with their green LEDs as the only light source within the room, that feels authoritarian. We are on one side, sitting; they are above us and freely omitting sound as we observe polite silence.

The act of sitting on the floor, presided over by speakers and surrounded by strangers, re-contextualises the space powerfully. As the piece begins to play, I already feel very aware of my body. The sound of my fingernails against the bottle in my hand seems loud and intrusive, and no seating position really feels natural.

As Saydnaya plays, we hear stories about the silent prison. With verbal communication punished by beatings, sound is weaponised and turned into an authoritarian tool to manipulate and dehumanise detainees. We hear guards taking off their shoes to catch inmates talking, finding excuses to inflict pain, and enacting the beatings that all too often slide into state-supported murders.

Solidarity is explored; stories of sick prisoners coughing (also forbidden) and unable to sustain the beatings in their weakened state lead to healthier comrades taking their place in an act of empathy. As the audio plays, I become more conscious of the social event going on just meters away.

I don’t feel like part of it. The sound of people laughing and networking leaks into the space. I want to say that it undermines the experience, but maybe that isn’t correct. It inflicts itself upon it, minimising the plight examined therein.

Many of those lucky enough to survive their stay at Saydnaya leave with their hearing severely affected from the periods of strain. Test tones play at different volumes, reflecting the sounds that ex-prisoners remember the guards’ footsteps at, both before and during the Syrian Civil War. As I strain to hear the lowest tones, I become aware of my own tinnitus.

I become aware of the pain in the tops of my eardrums and the dissonance that comes from trying to make sense of a near-silence. Disregarding the leaking noise of the crowd, focusing on Hamdan’s work, focusing on the stories and the decreasing volume, the discordance of this near-silence ringing in unison with the din of what has begun to sound like a party.

With Saydnaya, Hamdan brings the conversation around freedom and the removal of freedom on a human level into a place where maybe they may not always be found. Authority has found opposition within his work, conceptually as well as material. His unique and powerful use of audio as media is what makes this work so effective.

In Saydnaya, Hamdan makes me acutely aware of sound. Sound is used as a vehicle for empathy, for education. The piece makes me aware of the functionality of sound in a way that I am normally not. In this, I am comfortable describing what he makes as both art and progressive and exciting art. I left the exhibition almost immediately, feeling it impossible to return to the crowd.