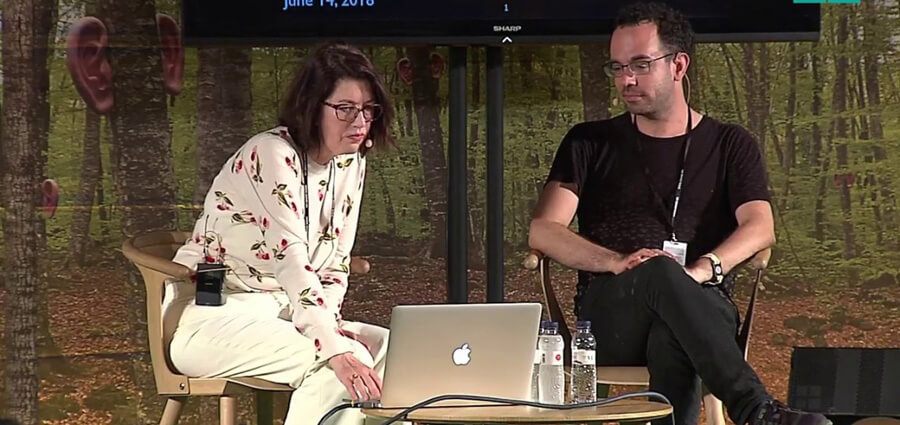

Interview by Bahar Emirzade

Susan Rogers is the director of the Berklee Music Perception and Cognition Laboratory in Boston. But before that, she became famous as one of the first successful female sound engineers in the 80s. In her talk in Sónar+D this year, she talked about her work in psychoacoustics as well as the inescapable: Prince.

Enduring the music industry for years, Susan Rogers, alongside her remarkable work in research, is most known for her work with Prince, surely one of the most famous names in the music industry. After 4 years full of endless hours of work with Prince, later with David Byrne, Tricky and many more, she quit and decided to get a PhD in psychology and psychoacoustics from McGill University. Her current interests in psychoacoustics include detecting diseases musicians are likely to experience, such as Tinnitus, as well as the psychological effects of music.

In her talk Musical Intelligence at this year’s edition of Sónar+D in Barcelona, she mentions how the sound waves affect the brain to create a happy-relaxed mood that otherwise is only achievable right before falling asleep.

As an expression of life, emotions, ideas and much more, music is a sui generis form of art. Unbound to language barriers, melodies are free from race, nationality or gender. Just like other forms of art, music feeds from the heart, but perhaps what makes sound so special is the fact that music is a unique way of expression interlinked with the sense of touch, making it more intimate.

Despite its importance in the development of cultures and societies, many aspects of music remain a mystery. This is where the contribution of science steps in. Discovering new ways of creating sounds and, more importantly, understanding why and how music affects people the way it does is a sector of science. Once fully uncovered, the scientific findings could introduce avant-garde approaches to music. From the music industry to academia, Susan Rogers jumped between tenacious fields and managed to make her name big in both of them. For this, she is an influential woman, a powerful figure illustrating how science and art can nourish each other.

For those that are not familiar with your work, could you tell us a bit about your background?

I’m a PhD in music cognition psychoacoustic, and I teach at Berklee College of Music in Boston. I teach in both the arts and the sciences. I teach music cognition and psychoacoustics, and I also teach record production and analogue tape recording because my background is in music and record making. I was a recording engineer, producer and mixer for 22 years from 1978 until 2000 in Los Angeles, New York and Minnesota.

I’m best known for my work with Prince. I was Prince’s engineer from 1983 until 1987. Then I made records until I had a hit album in 1998 with Canada’s Barenaked Ladies. From there, I transitioned to a student in the sciences.

Prince’s sound engineer and David Byrne’s producer. What did you learn from them?

With Prince, the job was to work very quickly because his ideas came so fast. My role was to make sure the signal was flowing. He could not tolerate technical difficulties. He had his instruments all around him so he could work, work, work, and go from one instrument to the next and get his music onto tape (this was the ‘80s, so we were recording onto tape).

Because Prince was his own producer, he didn’t spend a lot of time changing the arrangements or experimenting with sounds. Prince often worked with his band to arrange parts, but mostly he had an idea in his head and he alone, one track at a time until it was completed. He did that very quickly. I also made records with Geggy Tah, David Byrne, Michael Penn, and many more… I had the opportunity to see how rare and typical artists work.

Working with David Byrne was great because he’s a very pure artist and very experimental. David Byrne is open to new ideas and willing to try new things. He has an aesthetic that he’s going for. What I learned from David Byrne and others was the great variety of musical, and artistic thinking and the minds of musical artists. We, engineers, support and facilitate music-making. So you learn to adapt your style to suit the artist you’re working with.

You hold a PhD in Music Cognition Psychoacoustics and teach music cognition in psychoacoustics and record production and analogue tape recording at Berklee College of Music in Boston. Could you tell us more about your current research?

I was particularly interested in auditory short-term memory, which is different from long-term memory. I wanted to know how acoustic waves in the air become transduced into music and how the brain treats musical signals.

Does it regard consonance and dissonance as different? Is an octave and a perfect fifth different from a tritone as far as the brain is concerned? We know culturally, they’re different, but what does the brain care about? So I explored that, but along the way, I became very interested in a very hot topic in music cognition, which is the difference between the musician’s brain and the non-musician brain. Musicians have more neural architecture devoted to processing sounds, and they can hear the local details of sounds that non-musicians don’t hear.

So, in general, I’m interested in how the musician’s brain develops. At Berklee, I can explore the difference between drummers, singers, people who play the piano and guitar, and people who play the horn. What I would like to know is how musical training in childhood shapes the auditory path. However, currently, the most important work I can do at Berklee and for musicians, in general, is to work on hearing health.

So lately, that’s been my focus. It’s great to have a well-developed auditory path, but if you can’t hear, it’s not going to serve you very well. We need the musical community to become aware of damage through prolonged high-intensity noise exposure. They should understand how the mechanism of hearing works and how it gets damaged.

We should regard intense noise exposure in the same way, we regard intense sun exposure. If you overly stimulate your hearing mechanism, you can lose it over time, so you have to be really careful. Hearing protection is something that is a passion of mine. I would like to help our young musicians at Berklee understand that there are new technologies for earplugs that will reduce the overall level yet keep the frequency response the same. It should be thought of as wearing a condom or wearing sunscreen—protection for a long healthy life.

For this year’s edition, Sónar+D presents five key topics: space exploration, music, audiovisual experiences, the Internet and intelligence while asking what the new creative and technological territories that remain unexplored are. What would be for you in these territories?

As far as music technology goes, this exciting time is allowing us to create musical instruments that don’t physically exist. So in the acoustic era, when I listened to a record, or anyone listened to a record, we had the option of fantasizing that we were in the room with the musicians because we know what guitars, pianos, keyboards and drums looked like.

We can picture ourselves there. In our new worlds that we can create with sound design, we can create sounds that have no physical correlation. That sonic world doesn’t exist. Sound designers can do sound paintings like abstract art that doesn’t represent reality. That’s a different experience for the listener because there’s no scene to imagine. You have to use your own creativity to imagine what might have made that sound. Now, I think that the future of music will involve innovation in sound design.

Psychoacousticians and sound designers will work together so that we can create sounds that fool us into thinking that a large object is actually getting smaller as it approaches us or that a sound source is jumping around in ways which would be physically impossible but electrically can be designed. It’s kind of like virtual reality technology with vision. However, this will be an artificial world of audio. That’s going to make music listening a slightly different experience going forward in the next 25 years.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

It’s probably a belief system. Beliefs are very powerful. Motivation and momentum, and intentionality are very, very powerful. When people believe that they are not creative, if they believe that they are not smart, they can stop themselves before they’ve ever had a chance to be creative.

Art and innovation need to be understood as thinking that results in many more failures than successes. We must explore our craft and be willing to do years of bad art, years of bad thinking, and years of stupid ideas that go nowhere because all of that is the foundation of good ideas.

So the enemy of creativity sometimes is a belief system that we either have high creativity or we don’t. Allow yourself to be yourself. Be your own work of art. And if you express yourself to the best degree you can, then you are your creation, and you will make other things that reflect yourself.

You couldn’t live without…

I absolutely need non-human species to see and, watch and think about: birds, dogs, insects, frogs, squirrels. It doesn’t matter. I entered the sciences because I am extremely interested in the brains of other species, how other sensory systems, other beings, how they hear and see and smell and touch and taste and what they do and what they think, and I have a craving to see them and watch them and understand them, read about them.

The central question in my life from down deep inside is what it is like to be another species. I couldn’t live without seeing other animals and thinking about them.