Words by Eleanor Wakeford

Defying fantasies of control, corroding internal integrity, and ignoring the borders that define and defend identity, contagion is considered a threat to individual, national and global security. [1]

— Alison Bashford and Claire Hooker

While not exactly the ‘great equaliser’ as espoused by celebrities and politicians during the current Coronavirus crisis, the contagious disease has a notorious disrespect for borders. It reveals the fragility of systems maintaining global, societal, and individual divides as it emphasises our dependence on the actions of others. While usual reactions to external threats attempt to reinforce these borders, [2] Marianna Simnett’s contemporary fairy tales take her audience under the skin to challenge distinctions between self and other:

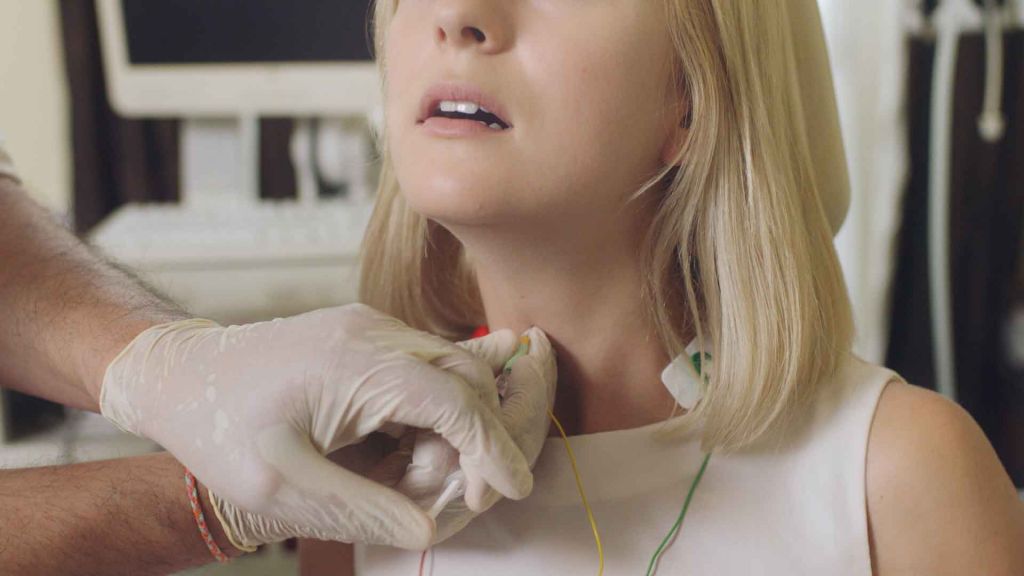

I [Simnett] watched the footage of my neck being punctured by that little hole and imagined the world being incorporated into the bottomless depth of my body. Dissolved of borders, I imagined not being separated by surface, the gloriousness of the utopian body that could melt into other beings, liquid-like, collapsing ‘hes’ and ‘shes’ and ‘theys’ and ‘wes’ through evaporation and perspiration, like this vanishing act accomplished through a brutal physical procedure. [3]

The ‘utopian’ or borderless body takes centre stage in Simnett’s most extensive piece Blood in My Milk (2018), a video installation that comprises four of her most important standalone works: The Udder (2014), Blood (2015), Blue Roses (2015), Worst Gift (2017). Weaving together these four chapters, Simnett foregrounds bodies that are under threat from internal or external forces; bodies that need to be controlled and contained. Increasingly, however, they are shown to be beyond medical control. In the clinical sites of Simnett’s narratives, bodies are revealed not as static vehicles for the ‘self’, but agential, rebellious, and distinctly ‘other’. As the borders between inside and outside begin to dissolve, Simnett destabilizes the ‘self’, the ‘capital I’, and instead highlights the dangerous yet radical power of ‘embrac[ing] otherness and accept[ing] it as part of ourselves’. [4]

Questions concerning selfhood and the ‘other’ lie at the heart of discussions of contagion, stemming from the association with ‘contact’ that differentiates it from infection. Deriving etymologically from the roots of ‘con’ (with, together), and ‘tag’ (to touch, handle), definitions of contagion have circulated around the idea of harmful contact: [5] ‘hurtful, defiling, or corrupting contact’. [6] Bashford and Hooker write that this focus on intimate, body to body contact meant that contagion invited ‘uneasy consideration of connections between things – people, animals, organic objects, intimate objects – things with which humans do not know, or always wish to know they are connected’. [7]

The body is represented, therefore, as a contested site; both protective boundary and potential site of contamination. The rise in ‘quarantining strategies’ during the nineteenth century, ‘of isolation, containment, barriers, the policing of spaces’, highlights the anxieties surrounding contagion and the threat it posed to the integrity of the individual and wider social body. [8] Bashford argues that this was part of a broader concern with distinguishing ‘clean and unclean, normal and pathological, healthy and unhealthy, self and other’ and the defining of ‘normal’ bodies. [9] In these binary distinctions, contagion is aligned with the unclean ‘other’ that threatens to pollute and destabilise the ‘self’ or the social body.

In this line of western thought, the female body has generally been associated with the ‘other’. As Donna Haraway states, ‘women are imagined … [to] have less selfhood, less individuation … less at stake in [white] masculine autonomy’. [10] This has played a role in the intense policing of female bodies and sexuality; bodies that have been marked both with less personhood, but also as a dangerous, contagious force:

The representation of female sexuality as an uncontrollable flow, as seepage associated with what is unclean, coupled with the idea of female sexuality as a vessel, a container, a home empty or lacking in itself but fillable from the outside, has enabled men to associate women with infection, with disease, with the idea of festering putrefaction, no longer simply contained in the female genitals but at any or all points of the female body. [11]

In Blood in My Milk, Simnett foregrounds female bodies breaching their borders, particularly through liquid and body fluids. The first two chapters of the piece, The Udder and Blood, draw together two liquid secretions associated with the pubescent female body: breast milk and menstrual blood. In both, Simnett investigates procedures and practices that attempt to contain the female body; in The Udder through the concept of chastity, and in Blood by drawing on a turbinectomy performed on one of Sigmund Freud’s patients, Emma Eckstein, to treat hysterical symptoms related to menstruation and masturbation.

Set on a contemporary dairy farm, The Udder juxtaposes textbook descriptions of the management of mastitis, a contagious bacterial infection in the udders of cows, with historically laden notions of chastity. Through Simnett’s wordplay, chastity and the strict surveillance of bodily borders are presented as the only protection against contagion and bodily invasion. We are told by the farm’s herdsman that:

Chastity is the practice of restraint. It’s about staying well behaved and keeping an eye on what’s right and what’s wrong. When used correctly it can be a powerful tool in preventing harmful diseases and unexpected attacks.

The udder is the protagonist of the piece, given voice by nine-year old Isabel who lives on the farm with her mother and two brothers. Isabel is presented as a stereotypical image of innocence, purity and beauty. On the cusp of puberty, however, she becomes a potential host for a different kind of contamination, one signified by her sexualized double, distinguished by her bright red lipstick: ‘the corrupter’.

Isabel’s mother’s warnings become infused with a dual meaning; regulating against infection alongside the policing of female sexuality and bodily borders: ‘She said that I was too beautiful to play outside’. Isabel and the udder become objects of strict scrutiny, constantly observed by Isabel’s mother, the herdsman, and multiple surveillance cameras to prevent the risk of infection or corruption through ‘exposure to the outside world’.

The paradox of a milk-producing yet chaste udder highlights the impossibility of fantasies of what Haraway would call ‘autopoiesis’; a body that is self-sufficient, able to reproduce and maintain itself. [12] While the herdsman explains the importance of chastity and maintaining sealed bodily borders, Simnett draws attention to the microbial life that already proliferates within the body, enabling the organ to function. Isabel and her family are depicted inhabiting the porous walls of the udder itself, portraying the dynamic and essential bacterial life that cohabit the body. The organ is constructed from a red scrim, a gauze cloth that can turn from opaque and impermeable, to translucent and porous, highlighting the fragility of the body’s boundaries. As the border between inside and outside begins to dissolve, Simnett challenges the notion of bodily integrity and the unified, autonomous self, instead foregrounding the body as a site of contagion, of intimate connections with countless strangers: ‘to whom does “our” refer?’. [13]

Drew Leder calls this the ‘absent body’: ‘the whole set of organs under the skin that functions as an absence, independent of the subject’s awareness or control’. [14] The absent body is both intimate kin and inherently ‘other’, operating beyond the control or direction of the subject, but on which the individual is dependent for survival. The otherness of our own bodies erupts into our consciousness when we are sick: ‘a body both threatened and threatening, an “it” that reveals itself as something different from me, something stranger and harder to control’. [15] Slipping through the translucent scrim, Isabel is depicted as the misbehaving absent body with an autonomy of her own. Unlike her brothers held within the walls of the udder, Isabel is marked as a threat to the body that she inhabits as she explores the dangerous outside world.

Questions around bodily ownership, autonomy and control spill into Simnett’s next chapter, Blood. Isabel returns as the central protagonist undergoing an operation to remove the swollen turbinate bones inside her nose. Again, Simnett uses a scrim to depict a corporeal interior that is both intimate and warm, womb-like and yet disconcertingly alien, even threatening. Two girls, playing both Isabel’s friends and her turbinate bones, spin Isabel while she begs them to stop. Isabel’s autonomy over her body is undermined and she is overcome by symptoms such as nosebleeds, stomach cramps and headaches. Yet while her turbinate bones are depicted as a threat, they remain intimate kin, singing ‘But we belong to your interior and you cut us out. / Without us you’re just a cavity, a sack of depravity’. In her analysis of Blood, Filipa Ramos asks:

do my bones continue to be mine after I’ve removed them from me? When they were inside my body, why did I call them ‘mine’ and not ‘me’? What is ‘me’ if not the sum of all the parts of this body I call mine? [16]

Despite interventions that attempt to contain and control the body, either through the language of chastity and disease prevention or medical procedure, Blood in My Milk suggests that contagion, this intimate kinship with countless others, is the nature of the body and of being itself. While Isabel sings that she would ‘rather be alone’, her turbinate bones continue to haunt her, both repulsing and enticing her as they threaten to turn Isabel into a ‘monster’.

In Blood in My Milk, Simnett’s protagonists embrace this otherness inherent in the body by becoming monstrous themselves. Simnett describes her girls as ‘revolting’, playing on its dual meaning to revolt and to be revolting: ‘Make yourself as ugly as possible … and I’ll smile through the blood as you look at me’. [17] The female body and its association with otherness, as lack or ‘cavity’, means that it is also a site of potentially explosive disorder: ‘a leaking, uncontrollable liquid, a formless flow … a formlessness that engulfs all form’. [18]

Blood, in particular, becomes a central image of their revolt, of transgressing borders, and the violent eruption of the absent body into consciousness, unsettling not just the individual, but the wider social body. In The Udder, Isabel slices off her nose in defiance of the restrictions placed upon her body, saying ‘Now let’s see who’s too beautiful to play outside’. This act of self-mutilation mirrors the story of Saint Ebba who, alongside her sisters at Coldingham monastery, reportedly cut off her nose to protect her virtue from invading Vikings. While initially repelled by the mutilated nuns, the Vikings later returned to set fire to the monastery, killing everyone inside. Like Saint Ebba, in cutting off her nose Isabel spites her face; as the alarm system sounds, it is clear her actions have led to the development of mastitis. Isabel is now a threat to the entire herd. To control the infection, Isabel is quarantined until she is ‘made clean’ by the herdsman who restores her nose.

In Blood, Isabel is offered no such resolution. As the gauze is removed from her nose, Isabel recounts the post-operative effects of Eckstein’s own turbinectomy as documented by Freud:

At that moment strong emotions were welling up inside me. There was moderate bleeding from the nose and mouth. The odour was very bad. Before anyone had time to think, at least half a meter of gauze was removed from the cavity. The next moment came a flood of blood. The patient turned white, her eyes bulged, and she had no pulse. The poor creature was unrecognisable. I felt sick.

As she speaks, a huge length of red fabric is pulled from a papier-mâché nose, depicting this powerful and unsettling breach of borders. The absent body erupts into an uncontrollable presence, viscerally infecting the bodies of those around, including Freud’s own corporal schema. The female body as ‘cavity’ is inherently leaky. Yet this potential to spill out beyond its borders marks it as ‘dangerous’, a transgressive, contagious force that threatens the parameters of the supposedly contained body of the white male ‘self’. [19] Like in The Udder, however, Isabel is not ‘made clean’. The audience is left with the image of her mutilated face that is as viscerally unsettling for us as Eckstein’s disfigurement was for Freud: ‘I felt sick’ he claims.

Simnett states that part of her work attempts to connect to ‘the inside of the person watching … an inside of my body connecting to the inside of your body’. [20] Assumptions of bounded, autonomous selfhood are overturned, and instead, bodies are revealed to be multiple, other, and inherently interconnected. The supposedly ‘already breached’ female body becomes a powerful, contagious force in Simnett’s work; systems of control and containment are undermined through the images of blood pouring down the faces of Isabel, Eckstein, and Saint Ebba, transgressing the borders between inside and outside, self and other. [21]

Liquidity and contagion are what Grosz calls ‘borderline states … disruptive of the solidity of things, entities, and objects’; [22] they unsettle the ‘status quo’ and reveal the gaps and faults in our own borders. [23] In my forthcoming article, I will focus on the last two chapters of Blood in My Milk, Blue Roses and Worst Gift, to explore how Simnett poses a logic of contagion, of radical interaction with the ‘other’, as a necessary act of resistance in a time of advanced capitalism.