Words by Maren Häußermann

Matadero in Madrid was a former slaughterhouse, and now one of the most important cultural spaces of the city was once again where the L.E.V. festival took place. It was the second time the L.E.V. – which stands for “Laboratório de Electrónica Visual” (Visual Electronics Lab) – came to the Spanish capital after its edition in Gijon, where it has its roots and was first celebrated thirteen years ago. Due to COVID restrictions, there were no live acts on-sight which made this year’s events different in Gijon and Madrid, where I participated for the first time in general. I found a very different atmosphere from the one my colleague experienced last year. It was a real virtual festival.

Entry was limited and only possible with previous reservations. We had to wear the regular mask covering the nose and mouth and one around the eyes to protect the VR glasses from our skin. With not only eyes and ears but also mouth and nose covered, I have to admit that at times, I needed to remind myself that I was still able to breathe so I would not panic. The glasses had to be cleaned after every usage, which robbed some time, as well as the difficulties technicians faced then adjusting the glasses without being able to put them on themselves.

The festival comprises three branches: Vortex on-sight, Ciudad Aumentada (Augmented City) in the area, and parts of Madrid and Planet L.E.V. online. The first one invited us to test VR and AR technology in the dark halls of the Matadero itself. In Nave 0, we could listen to the sounds of Sigur Rós and alter them by touching with our hands the virtual forms appearing around us. Lifting them up would increase the sounds giving them a shrieking, almost dreadful tone. Figures reminding of hearts (the organ) would pump tones in and out in a regular beat, calming the oeuvre.

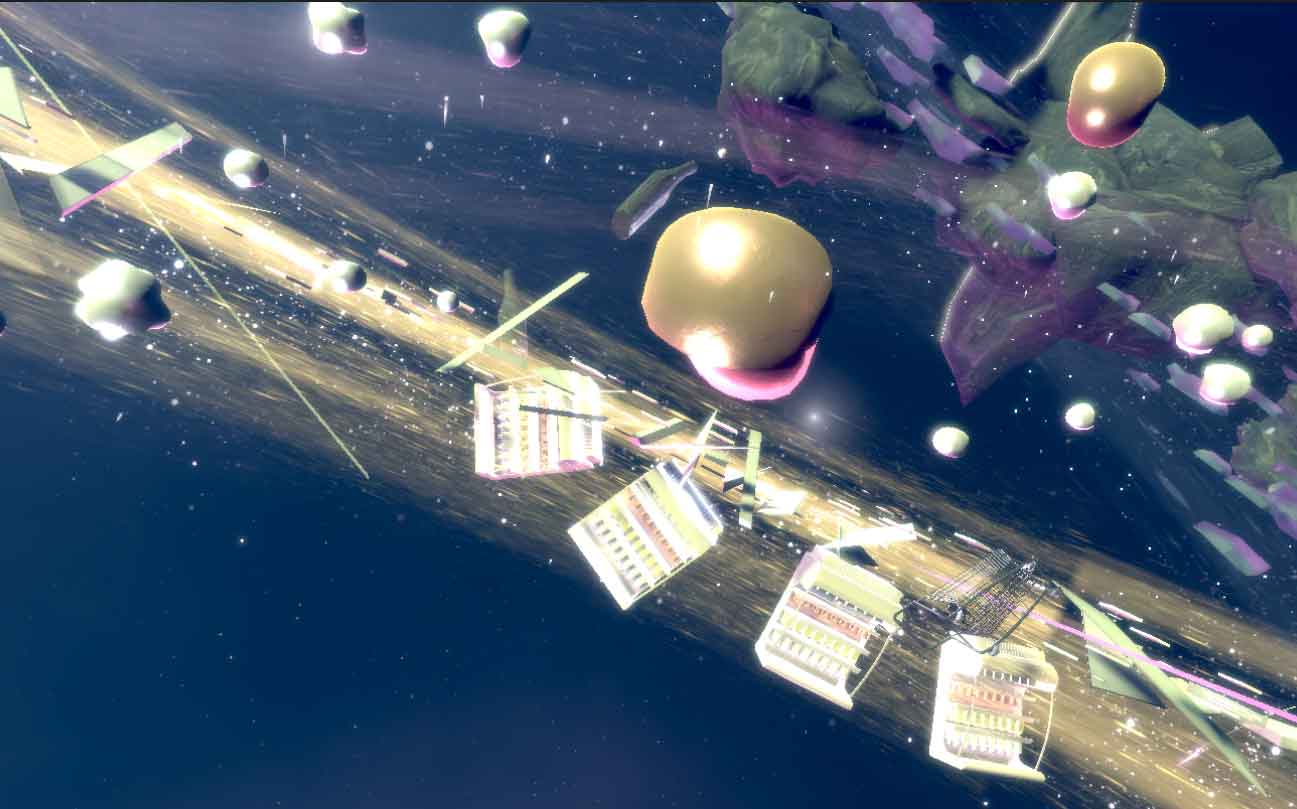

Also interesting in this regard was the Symphony of Noise VR part, which consisted of four chapters. We found ourselves in different scenes, surrounded by various objects. With the remote control, we could move or destroy them and thereby change the sounds accompanying the experience that was designed by Michaela Pnacekova and Jamie Balliu and inspired by Matthew Herbert’s book The Music, in which the artist and musician create soundscapes by the association in the mind of the reader.

With the Spheres projection by Eliza McNitt in the Archivo, I found myself in space, where I saw how the planets appeared around me. I could move them with the remote control and look into them by moving my head. I would hear their magnetic fields’ sounds and get sucked into a black hole. In three chapters, the voices of Millie Bobby Brown, Jessica Chastain and Patti Smith explored with the audience the human connection to the universe.

Above the Archivo was the entrance to Planet L.E.V., a virtual landscape created by the Children of Matadero. Here, with VR glasses, the audience could explore the works of different artists like in a virtual gallery. With the remote control, we could walk through and thereby slowly discover the area or just pick concrete places on the map to go there directly. The technology made it possible to climb the mountains, walk through grass and go into various installations. The scenery reminded me of a mixture of northern landscapes, icy nature and vast deserts.

Among the works exhibited in this virtual world was Spin by visual artist Lucas Gutiérrez and composer Robert Lippok. An audio-visual installation of two vertical rings hovering and slowly turning above the ground. A meditation space where sounds of nature and civilisation meet, and chaos, silence, wildness, peace, evolution and disaster are in constant motion. The artistic collective MSHR/Birch Cooper and Brenna Murphy presented the Concentric Core Reflector, a sculpture where synthetic forms reflect organic systems. The audience could enter the work that reminded them of a building and discover it from the inside.

On the third out of four days in Planet L.E.V., I saw a life set by music producers Sinjin Hawke and Zora Jones. After entering the live area by pointing the remote control on a small pyramid, I found myself in what reminded me of a huge public viewing area. Around me, there was no sunlight, only a soft glow on the horizon. In front of me, on the wall, I could see abstract figures moving in an interactive experimental performance.

Outside the buildings was the Ciudad Aumentada, a virtual world made accessible with the help of different apps. Among other things, we could see a sculpture created by local artist Claudia Maté. Not only in the Matadero area but also in three other places all over the city, we could see its variations.

On the walls of the buildings, on-sight were paintings of small creatures which came to life on the smartphone displays when the cameras were directed at them. In the Taller, another building on the premise and part of Vortex was a 3D cinema in which the seats were arranged at a two-meter distance to each other and on which we could move around to see what was happening in every direction.

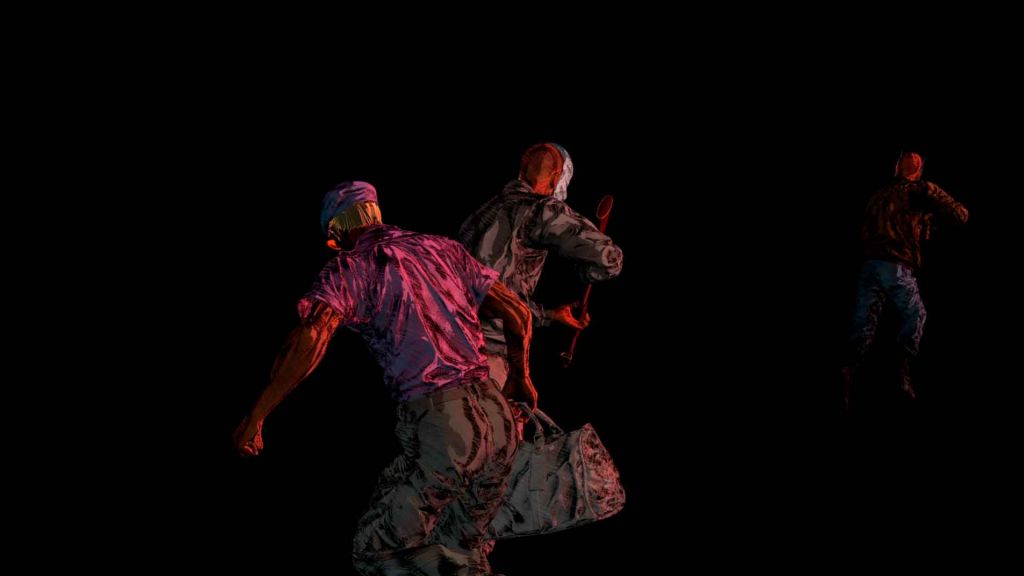

I was fascinated by the VR film Black Bag by Chinese director Qing Shao who used a hand-painted art style to create a twelve-minute intense, high-quality thriller. I found myself in the scenery, caught in a dream, a money heist, a shaft that I was trying to escape being put in the position of the protagonist. It was not the only time that I felt a bit nauseous.

The all-over experience of L.E.V. Matadero 2020 was impressive and contemporary. Although the lack of live acts and the small amount of audience created a not-festival-like and individualised atmosphere, it also made it possible to appreciate the artists’ works profoundly.