Interview by Silvia Iacovcich

As nature preservation has become a major global concern, artists Rachel Pimm and Graham Cunnington scrutinise the magnitude of the physical world and its undisclosed history, exploring the concept of memory and human integrity. The duo likes to wipe off the dust from what we can’t perceive through projects that are imbued into layers of punk, science and contemporary art.

The two artists have been recently guiding us into the realm of matter and its archival weight: an earshare/to cassay the earth crust, is a multi-format project on view via Afterness Online, analysing the consequences of our intricate relationship with collective and organic remembrance.

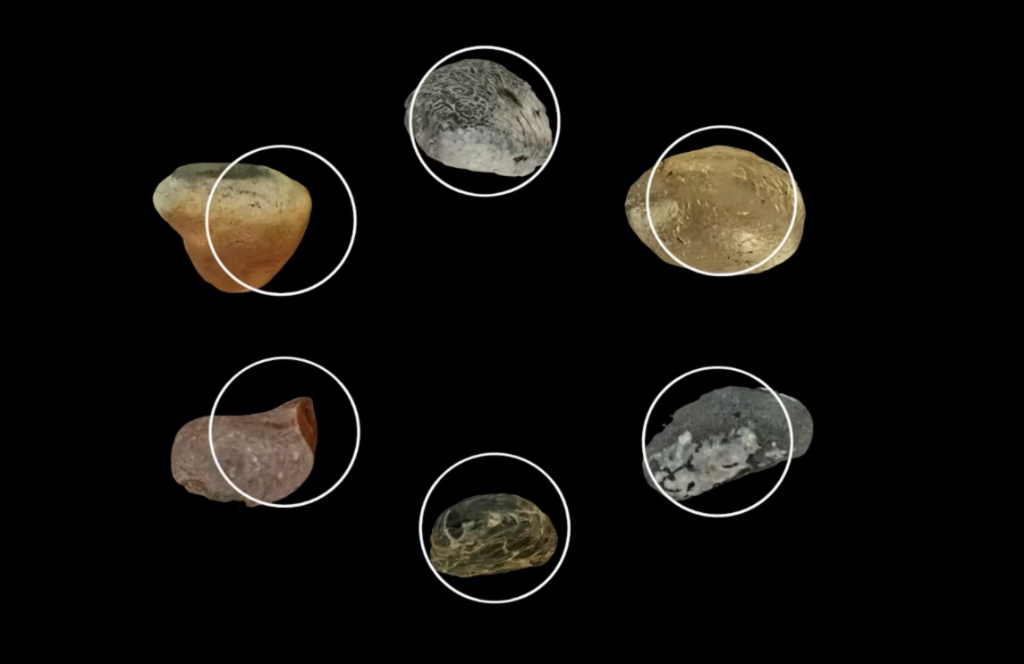

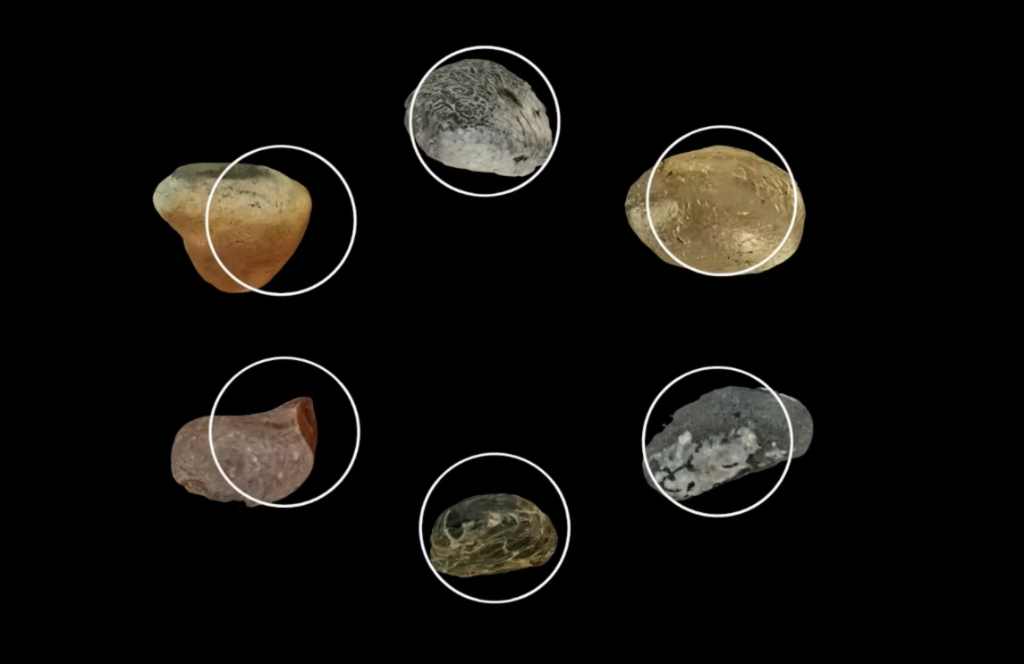

Scraping through the historical camouflages and references disseminated around the land of Oxford Ness – a decommissioned military testing site, where research into weaponry and covert radio systems was conducted between the First World War and the Cold War – a pebble is turned into an energetic narrative tool, showing us the bond that links human actions to environmental alterations.

Geology becomes a lens in the artist’s hands that conveys a sense of constant, mutable state, in a display that shows how our earth silently absorbs the impact of our societies. The result is a deserted land that speaks: a forensic journey that expands through lapsed chronicles and quantum mechanics to point out that nature’s awareness and its oblivion is inexorably connected to the loss of our collective (and perhaps spiritual?) identity.

The duo’s projects are always palpable immersions into deductive, methodical observation, routing through disparate connections, using low-cost and tech material as the bases and media of their artworks – where inanimate features loom in their wisdom to tell their own tales.

In India Rubber, the audience examines how rubber turned into a currency of global trade, interpreting its path from plant factory to the final product: a significant segment in our ordinary lives, passing through unobserved. An inquisitive search that measures the density of human economies in production, focusing on human implications in our global future.

Searching for the perpetual relationship between nature and human-made products – Graham does it with sound, Rachel with images – their values are shared and combined through their experience of political activism, protest and counter-cultures: resilient, collaborative, creative, and unconventional, they vocalise the need for a change of perspective – reflecting on perdurable and unchanging bonds that can’t be simply washed-up into a cumulative amnesia.

Graham’s experience fits in perfectly with Rachel’s visions; he’s a founding member of the industrial collective Test Dept, and his meticulous sound investigation stems from political situations, music, science, indeed “all aspects of life”, as he mentions in this interview. Dissecting basic elements of the anatomy of sound, he produces soundtracks of elapsed reverberations that come from situations and surroundings, giving the sound a new expression, letting the antimatter be vocal, and manipulating sources that combine into a parallel journey to vision.

While technology advances, Graham and Rachel’s artworks seek to evoke new feelings and let the audience reflect upon its intrinsic role on earth, a reminder that the viewer is part of the whole, shaping our landscapes, creating characteristic heterogeneity and biodiversity patterns – and that nature is a mirror that reflects our blows.

For any of our readers who might not be familiar with your work, when did you meet and what have been your biggest sources of inspiration in your careers?

Graham Cunnington: We met while working together at the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton, London, which was quite a special place at that time, an incredible hub of creative people who used the flexibility of the job as support while developing their work. It was also a place of solidarity and activism, which through periods of strike action, we tried to drag the pay away from poverty wages. Rachel and I knew something of each other’s work, but it wasn’t until later, when Rachel asked me to work on the soundtrack for India Rubber, that we started to uncover the complimentary creative values and ideas we shared.

Rachel Pimm: Yes, the Ritzy was a really important place for me, too – much more of a queer and culturally diverse place than most art schools, for sure. Also refreshingly politicised. Being part of a group taking industrial action together produces very real solidarity. Things, places and people are inspiring. My behind-the-scenes conversations with individual people whose curiosity and desire to learn are always the most inspiring. Other artists, chefs, writers, musicians, climate activists, gardeners, scientists…

The list is long, and anyone who has had one of those behind-the-scenes dialogues will know who they are. Often, it’s the recommendations that come out of these – a book, an event, a material, which challenge me and change my whole path. I learnt that another friend and collaborator who I have also been lucky to work with, Lori E Allen, was an archaeologist. I like that meandering and tangential biographical details come up the times when you are speaking with someone on time, paid by someone else at a paid job, and you’re not there with them to take something from them, so the meandering takes you elsewhere.

Now, perhaps as I’m employed more as an artist, I find myself meeting people with a bit more of an intention, based on their accumulated expertise, in a more focused way – with an agenda. But actually, working with friends or people you meet in a sideways way, organically, I think, has been much more rewarding, like adding something to a friendship.

GC: I’ve also taken inspiration from the people I’ve met, developed ideas and worked with over the years. Inspiration has come from film, music, politics, locations, science, and all aspects of life. I feel inspiration is a continuous process of development and discovery; however, early specific sources are the DIY aesthetic that developed from Punk, although musically, the post-punk experimentalism in the immediate aftermath was more of an inspiration.

The explosion of creative ideas of the ‘Proletkult’ movement from the early revolutionary period in the USSR; Pierre Schaeffer’s Musique Concrète and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop; the ongoing fight against the politics and consequences of the neoliberal period.

Afterness Online is a series of digital commissions inspired by Oxford Ness and the intersection between present and past. Can you describe the creative process? What were the main challenges behind an earshare/to cassay the earth crust?

GC: There are so many interesting aspects to Orford Ness, with the history, particularly the military history of the last century, with the uniqueness of the landscape with its strange structures and its flora and fauna.

But it was also its sense of the hidden, the unspoken that drew us in – though we had an idea of what went on there, from the research of archive material and talking to the people who work there and know the history – we still couldn’t quite place it, didn’t really know. It was an investigation into that aspect, and that led us to explore what could be witness to those hidden aspects, hence the pebble as the central character.

RP: The landscape of the Ness is pretty inaccessible- hard to travel to and unforgiving in terms of comforts. We were lucky in the way the commission unfolded because we were able to attend the opening of the installed works before we had finalised our own contribution, and that gave us the space to learn from the work we’d witnessed and apply that.

One thing we felt we wanted to do was to avoid being only poetic about the eerie. The violence was quite tangible to us, and we didn’t want that to get hidden or softened. This meant not shying away from some of the uglier subject matter.

GC: Yes, the place has such an otherworldly quality that it would have been easy to make that the focus, but for me, it was also the unspoken questions in that landscape of what this was all for; why these tests were being done and what would be the real-world result of the experiments?

RP: Yeah, we could guess at it, but I’m sure the reality would be worse and weirder than we imagine. Personally, also, I felt like there was just so so much to condense into a screen – military history, biochemistry, literature, physics, mythology and the types of imagery which ranged from microscopes to 3d scanning. And in order to include it all, it took a while to settle on a good form to hold it and then making was frenetic and quite gruelling. Many long hours and last-minute improvements.

GC: We discussed having different approaches to it, which became the multi-format work it is, although it needed to be screen-based for the online platform. Two films arose out of that condensing of so many aspects, along with the separate text and images: part 1 is research, image and dialogue focussed; part 2 allows space for the sonic element to come to the fore.

RP: In terms of the components of what you’ll see going into the imagery, I found myself looking for some of the etymologies of the language of the quantum in Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, which turns out to become a very useful storytelling device – its obfuscation and hybrid writing style was a mirror for my experience of looking at the site and seemed to also tackle the scale and abstraction of the violence.

Then the motifs of various enigmatic objects like the flashes of yellow poppies and the salt-loving vegetation, as well as the chemistry of the buildings and their own place in the calcium cycle, complicated the architecture and its decay into the bodies that have also been lost. A lot of collaging later, and it works more like a container of the question of ‘what took place?’ and ‘What is it made of?’ which is, I suppose, always my question.

I was also really open to expanding on this idea of bones and shells in conversations with Gray about our own experiences of our bodies in physical pain, which comes full circle to the audience of the work – online allows access for anyone who can’t get there.

GC: I really like the way that Rachel’s enquiry opens up channels that are not immediately apparent, the weaving together of disparate connections. With the components of the sound, I wanted to create the sonic journey by referencing those varied elements while limiting the sound sources to the elements that were present on the Ness.

We were lucky enough to be able to stay on the Ness for a couple of days, and I recorded so much material. However, it emerged that the main element would be made from the pebbles and their interaction with the environment or the empty buildings. There are also elements made from the sonic properties of the metal railings and stairs from the Bomb Ballistics building, which have a unique tone when struck and a hum when the wind is passing through them.

So the whole soundtrack is basically composed of about 90% pebbles, with some of the metal railings and brackets, wind and sea manipulated through sound processors in the studio afterwards.

Your collaborations span a range of years and projects: India Rubber, from 2015, was a documentary-style video following the evolution of the finite natural resources of rubber, converging technology, industry and economy into a work of art. Scientific method and exploration of the creative process become strongly aligned in your projects; inquiry is at the heart of both of these methods as if art and science are two ends of the same process – was this duality your intention?

RP: The rubber project was one of those conversational tip-offs – another artist I met told me you could visit plantations and watch the tapping in forests early in the morning. Then once I’d seen that the whole process opened out to me – each part leading to another. I was just curious to see as much of it as possible. Manufacturing being outsourced means we don’t really know how things are made.

This was actually the start of my working relationship with Gray and the way he uses sound. I was really struggling to edit the volume of material I had, and my partner at the time (who had taken most of the recordings to free up my hands for the camera) suggested I work with someone who could compose a soundtrack.

The sound of each location seemed to shape and voice the story of this thing in transformation. I immediately thought of Graham and how he would open it up, and I was very lucky; he said yes to scoring my edit because it has completely transformed how I think about sound since. I now think of it as a way of using voice without the anthropomorphic desire to speak ‘for’ or the default colonial-financial imprint of the English tongue.

Sometimes I have a lot to write, but if I want to avoid speaking on behalf of something, I’ve since found that sound can leave that open. It feels like Gray’s soundtrack recontextualizes the extractivist subject matter into a new language and can allow ethics of close listening.

Though the collaborative projects we are discussing have been initiated by me, I am very influenced by the historical biography Graham brings. Anything industrial and historical, I tend to think of his work. Of the politics he brings.

GC: Rachel handed me many hours of sound material from the original recordings, which I went through, without reference to the original footage, to pick out small cuts of sound that I felt were interesting in themselves, and could be manipulated to build a resonant journey that worked with the image. Although it was all original source material, and in small parts crossed with the source filming, it was not a naturalistic soundtrack. I wanted to support the film with an energy that came from the source but which expressed that parallel language.

Rachel, you co-founded the artist-run project Auto Italia South East in 2007 – the space targets programming focused on new artistic formats through a collaborative approach. How do you see Auto Italia and its evolution in the next few years, and how do you see the role of technology in our physical spaces?

RP: I’m really proud to have been able to be part of the history of the project space. Whenever anyone asks me about this, it feels a little disingenuous to answer, given that my years of involvement were so long ago now, more than a decade, and the number of contributors and evolutions that have taken place since are many.

I watch on with real admiration for its continuation and feel really happy that it went on to be this sustainable. I don’t think it was a great time of my life- happiness-wise- and I have reflected on that time period so much, on how to improve my boundaries and working relationships, limit how much of a workload I take on, how to work equitably, and how to look after my mental health. Perhaps I enjoy starting things more than seeing them through.

Or perhaps there’s an opportunistic nature to how I like to work collaboratively, carving out new spaces for others to take up. I have no idea what they’ll do next, but I know it will be so much more expansive than any of us thought at the start.

As for the role of technology? I honestly feel like less is more. To me, technology means more than just screens, AI and space colonisation (none of which pose much of a future to me); it can also mean growing things, language evolving, unlearning and more, but at a slower and more sustainable pace. These technologies of mutual aid are the technologies I’m interested in, ones that have the potential to massively re-distribute power away from where it’s been historically concentrated.

Gray, you and I have talked a bit about spaces being less available now for squats or urban exploring as a result of the gentrification of cities, changes to empty buildings, landlords, property law, policing, civic liberty around ‘public’ spaces and more. I think we’ve spoken about how both of us are not sure how it would look were we to start working now, given the differences of availability and the price of rent. Do you have any thoughts on that?

GC: Yes, definitely! When I was starting to work in the 80s, signs of the decline in manufacturing were all around, and the urban population had long been shrinking (strange to think when you see today’s proliferation of mass building projects); there were empty houses, factories, warehouses and disused land all around us in South London. Squatting was still legal, and small independent housing co-ops started up everywhere. These spaces provided cheap or free housing and spaces for creative work.

It also led to people coming together in groups or collectives as some things could be more easily achieved with shared skills. This also meant the development of creative spaces and social centres, which enabled ideas and political activism to develop. I realise that we were so fortunate to have that, although living was far from easy.

That coming together is so much more difficult now – although technology has created new types of space for interaction – and the scarcity of physical space is a major limitation. Perhaps new opportunities could open up with more flexible work patterns and less need or desire for fixed work environments, as there is definitely a need for change, although the comforting pull of the previous normal might stall that development.

Graham, you are one of the founding members of the British industrial music group Test Dept, one of the most important and influential early industrial music acts. The approach of the band was marked by the use of ‘found’ materials, of making ‘more’ with less, through a political lens on the artistic world. Are there elements you have maintained from the switch from musical to video projects/installations?

GC: The two elemental threads weaving through my work are the use of found sound/materials and the search for a political and/or social context for the work, especially with Test Dept. These elements are present in the video/installation work.

However, whereas the work with Test Dept was more about using found sound, materials and locations in a larger context, I am interested in the forensic examination of sounds, as in an excavation of sound material, be that field recording, dialogue or short sample, to uncover the deeper aspects resonant in the subject, site or source material. This also applies to a continued interest in uncovering the human aspects and consequences of a subject.

Collaboration has also been a major element I’ve carried through to much of my work; I find that I get to discover more, gain knowledge and new ideas and learn more about myself, and hopefully give the same, through that creative interaction.

You worked together on an audio performance piece at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry for Nocturnal Creatures at Night in 2018, reanimating through sounds a space that was once the founding house of the bell Big Ben. How was the process of research and ‘building’ of old and new sounds?

RP: The bell foundry was one of the few industrial places I’ve worked where I wasn’t supervised in some way or discouraged from crawling around dangerous holes. That meant I could go at my own pace to find things. Little scraps of metal or handwritten notes in the workshops, old tools – clues that I could follow up as to the labour histories. ç

An ingredients list. Horse and goat hair, loam, tin, copper, water. And then a list of instructions written on the floor. A recipe. Actually, casting is a lot like cooking – there’s a technical side to what quantities and materials are involved, heat and time-based processes.

The life in guardians performed alongside a former member of staff – and the actions that took place and materials used were those I learnt from the outgoing owners and their hundreds of years old relationship with suppliers (some of whom sent me samples and images to use), so the commercial change over of the property from the site of labour to development was really present.

We made a kind of silent workshop with a live score – 4 hours of sound – which took the place of the now-absent sounds of bell-making. Ghosts of industrial processes. One of the many things I learnt is that British bells historically have a sad tone to them. We apparently love to commemorate a moment with sombre sounds.

We didn’t make a recording. I’ve often wished I could listen back, but its ephemeral nature was probably more appropriate. There were a lot of people in the audience who were there to listen to the whole duration. That felt really special.

Usually, viewers of my performance work don’t stay that long – they look at it all, get a sense of it, and then move on, having experienced a part only. Perhaps Gray’s audience privilege duration or have more openness to that endurance. Perhaps the public interest in the charisma of the building itself had an impact, but the openness to that endurance was impressive.

GC: The Bell Foundry was another special place with such a unique and important history – both Big Ben and the Liberty Bell were made there. The sonic elements of the piece were taken from recordings made at the foundry together with recordings of the materials that Rachel had gathered (the sound of horsehair falling and landing on a surface, the mixing of ingredients, etc.), plus some archive source material like an old film of bell manufacturing.

There were still some bells dotted around the place, both large and small, and a lot of the machinery was still there. We made sections relating to the elements and processes that went into the making of a bell and linked them to the specific tunings involved, and that fed into the creation of the work and the cycles of the performance.

It was also something that very much related back to my work with the Test Dept, where we would develop work in empty industrial spaces, pulling out the ghosts of their pasts, not only to uncover those stories or hidden histories but also to present or illustrate present-day relationships or social issues.

Sonically, the piece for me was partly a celebration of the creations, processes and people who worked there, but also a kind of elegy for the building and its industry. It is interesting what Rachel says about the sound of British bells having that melancholic tone to them.

The Whitechapel Bell Foundry was the oldest continuously running company in Britain, and its demise was due to a number of reasons, not least the decline in demand and rising costs, but although not the main reason, the changing demographic of the area must have been a factor and the mist of gentrification hung over the place with its imminent transformation into a boutique hotel.

What’s the chief enemy of creativity?

RP: Lack of curiosity and inability to change your mind when presented with new information. People who think they already know everything are missing out on a lot. Perhaps also too much self-criticism and self-doubt because overthinking it, along with useless emotions like guilt and shame, can really stop you in your tracks. As can stress. Also, given that we are talking about collaboration, I think isolating yourself makes you less creative. Working together tackles everything. Including big power structures which need to fall.

GC: Agree with all that Rachel says. Self-criticism and self-doubt are the main ones, wherever and however they arise and finding ways to understand and overcome those obstacles are important in a creative path, although they can also have some positive aspects in helping to focus work and reveal stuff about ourselves and develop creatively.

RP: I also think it’s almost so obvious this shouldn’t need saying, but lack of safety, precarity or oppression are huge obstacles to making. I wish there were a universal basic income so everyone had the opportunity to meet their basic needs and then explore their creative potential. We’d have much better art.

You couldn’t live without…

RP: eating well and sleeping well.

GC: ditto that! Some form of an audio recording and playback device, too, maybe.