Text by Simon Coates

A pandemic while we’re in a global culture and information war wasn’t the scenario I was hoping for. Instead, it’s been a clear signal showing problematic global inequality and our societies’ vulnerabilities to propaganda. How easily divisive rhetoric can drive people into small cultural clusters stigmatizing others and helping to weaponize information in these times.

Dutch-born, Berlin-based artist Constant Dullaart is reflecting on how the coronavirus pandemic has affected society. And how has he been affected? It’s been a surreal reflection of my social anxiety; perhaps it will turn cathartic. Catharsis is something of a speciality for Dullaart. As is highlighting divisive rhetoric. Marked – not unfairly, it turns out – as an enfant terrible of the post-internet art movement, Dullaart is a disruptive influence with an altruistic mission.

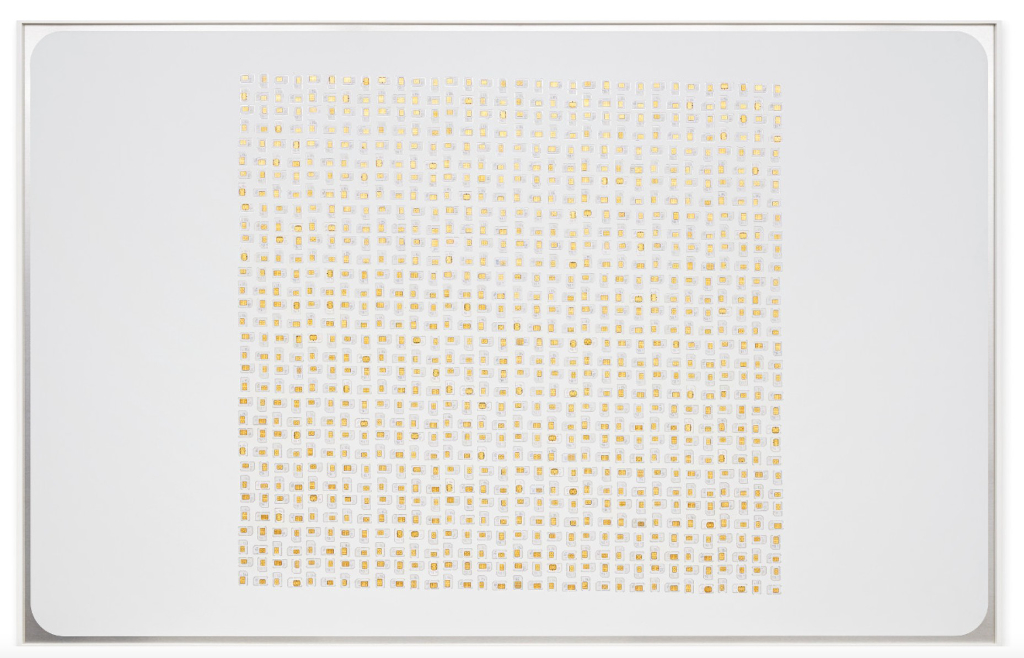

For his 2014 artwork High Retention, Slow Delivery, Dullaart created a kind of web-based level playing field by purchasing 2.5 million fake Instagram followers and distributing them evenly across what he saw as key art figurehead’s Instagram accounts so that each one was followed by exactly 100 000 accounts, both fake and real. The bogus followers were bought on eBay, and the Instagram accounts that benefited included those of über-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and artist Jeff Koons.

The definition of social capital (the network of relationships that hold a society together) in the twenty-first century has shifted to include the validation provided by approbation on social networks like Instagram, something Dullaart is keen to highlight. The fact that one can feel to be hoarding quantified social capital is closing minds, he says. Through targeted advertising, invasive behavioural tracking and loss of privacy, identity has become a precious commodity. As a result, much of society is getting defensive and more conservative in fear of change.

For 2015’s The Possibility of An Army project, Dullaart recruited volunteers to create five thousand fake Facebook accounts. Each account was given the name of a real soldier recruited from the German state of Hessen-Kassel by the British army to fight battles during the American Revolutionary War. Six years later, the fake Hessian soldiers still maraud the Facebook foothills, spreading fakery as they go.

The artwork was a prescient comment on social media manipulation and how fake accounts are allowed to wander unchecked across the platforms. One year after Dullaart launched the project, Donald Trump was elected US president, and the UK left the EU on the back of, amongst other strategies, the robust use of targeted Facebook advertising and social media analytics. Constant Dullaart had made his point.

Why does the number of followers a social media account has make such a difference? And how do we know which accounts are real? Facebook, Twitter and Instagram are flooded with fake followers that can be bought online via increasingly simple processes. Platforms that employ user-driven content – feedback, reviews – are also susceptible to hype. For example, online watchdogs Fakespot suggest that up to 60% of reviews for a product on Amazon can be fake. On the other hand, there are multiple stories of serial reviewers writing positive reviews in exchange for free products.

These flagrant abuses of the world wide web, and all that it has to offer besides, are concerns that intrigue Dullaart. The term ‘post-internet art’, incidentally, was coined by American artist Maria Olsan in 2006. Somewhat confusingly, it doesn’t mean art after the internet. It means art created using the possibilities that the internet presents, from the technical (bots, apps, memes, crowd-funding campaigns and algorithms) to the emotional (togetherness, vanity, entertainment and paranoia).

Dullaart also uses the term ‘internet-aware art’ to describe his work, …since it would make the relationship to the medium more implicit. The idea behind post-internet seemed to be that networked culture – something many people call internet – had become so ubiquitous that one could only think of a world or artwork that included it somehow. And that the significance of the internet moved beyond the point of it being relevant enough to discuss. I still think this position is naïve, apolitical to the point of dark sarcasm, yet excitingly simplistic.

One notable by-product of the post-internet art movement has been the dissemination of the NFT (or non-fungible token). While the layperson can be forgiven for thinking that NFTs are nothing more than very expensive animated GIF files, the art world is currently trumpeting their advent as a breakthrough in artwork as a commodity.

In March 2021, Twitter founder Jack Dorsey sold his first-ever tweet as an NFT for more than $2.9 million. In July, Reuters reported that the NFT market was worth $2.5 billion and growing. What does Dullaart think of NFTs? The NFT is not yet an art form. It can become one. I’ve been experimenting in the field since early 2014 and strongly believe this is a way to make the art world more interesting. But for now, it is still an extension of existing, previous forms of art – like generative art – and not used to its full potential yet. Is the financial side a distraction?

Hopefully, the speculative bubble won’t remain distracting forever. It is still very self-referential, hinging on the artificial relevance of systems that appear to be a black box of magic to most people. Dancing around the mystery of a few lines of code is not going to keep us warm for long. But the idea of commodified actions will.

Not content with simply pulling the rug from beneath pervading internet modes of behaviour and commodification, Dullaart is redressing the balance by launching its social media network. Common Garden is an ad-free, web-based space where registered users can build their own social environments and interact with others.

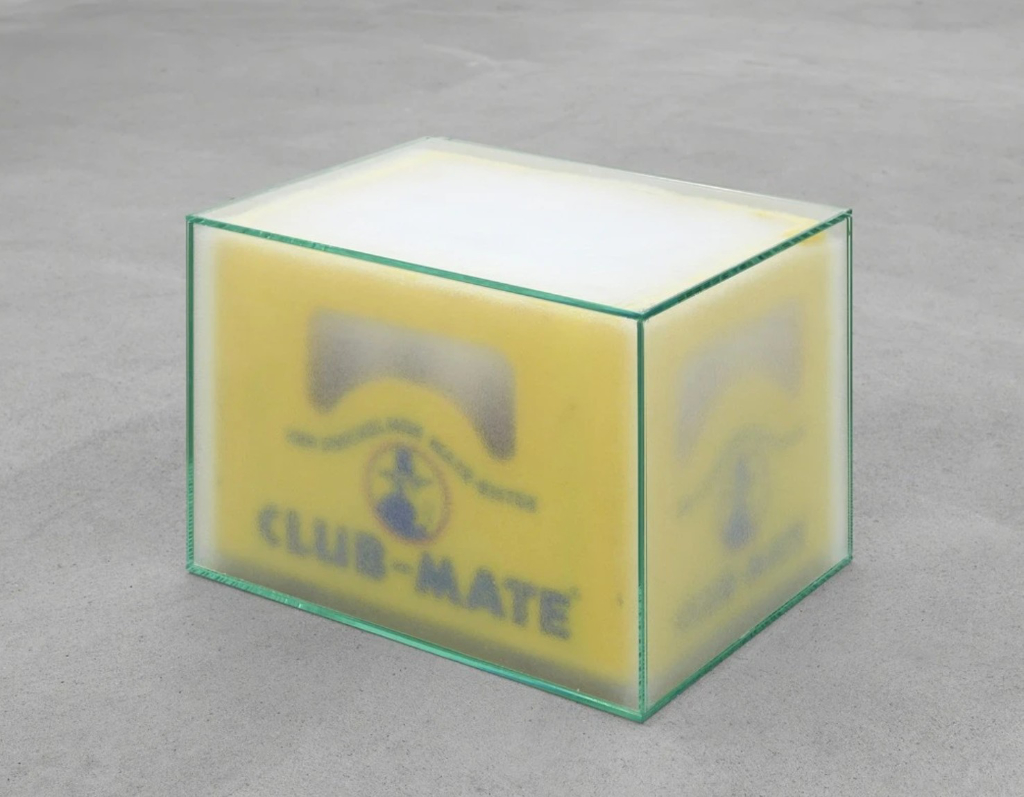

Dullaart has already used the platform as a virtual site for his most recent exhibition, This Unjust Mirror, wherein online visitors can peruse the show’s artwork remotely, led by video, embedded sound and images. Using the Common Garden is a dizzying experience that fits perfectly with Dullaart’s vision of the internet as a blank medium that can be disrupted for the greater good rather than existing as a place for exploitation and uncertainty.

Taking the form of commentary on a global, social scale, Dullaart’s investigations uncover and ridicule the psychological viruses that stalk the internet. It must be wearing to inhabit a world packed with serotonin fixes and doublethink, though. What is it that keeps Constant Dullaart going? The joy of shaping something oppressive – like a social construct exploited for commercial gains – into something symbolic, something playful, human and fun with a simple gesture.