Text by Lyndsey Walsh

Art & Science Node, a Berlin-based platform for art, science, and technology intersections, in collaboration with the EU CHIC Innovation Consortium, a research and innovation project supported by EU Horizon 2020, has brought together an extensive gathering of scientists, artists, innovators, and experts working in and around the disciplines of art, food, health and agriculture for their program Our Bio-Tech Planet: Future of Plants and Humans.

Our Bio-Tech Planet: Future of Plants and Humans, which took place in Rome’s historic Botanic Gardens, aimed to foster new dialogues concerning the vegetal realm and our future through workshops, an exhibition, talks & panel discussions, a video program, live performances, and AR experiences.

Weaving narratives between kingdoms and disciplines, Our Bio-Tech Planet examines our present fraught with crises and ecological devastation and asks how the future can be shaped and steered toward a more hopeful and sustainable vision. From this imaginative and critical lens, the curatorial team has brought together artists Jill Scott, Marille Hahne and the artistic collaboration between Alex May and Anna Dumitriu as their artists in residence.

Works of the events’ Rhizospehre, including artists Joanna Hoffmann and Andre Bartetzki, Larys Łubowicki, Paulina Misiak, Jadwige Subczyńska, Piotr Słomczewski and the programs’ Future of Plants and Humans artists Sanja Andelković, Funda Zeynep Aygüler, Ismaele Bonomi, Lilia Chak in collaboration with Olga Kisseleva, Neo Christopher Chung with George Dyer, Tuana Inhan, Rob Kesseler, Olga Kisseleva, Yujue Liang, Maisha Maene Miyuki Oka, Felicitas Rohden, Eric Schockmel, and Laurent Mignonneau and Christa Sommerer.

The topics and themes in this programming feed into the critical discourse woven into its additional panel talks and discussions, featuring topics such as How Artificial Intelligence transforms our understanding of biological systems led by Prof Krzysztof Krawiec to How to survive in an increasingly competitive world? Led by Dr Alex Krawiec.

In creating this variety of programming, curator Juliette L. S. Wallace shared with us some insights into the process of bringing together all these different views.

Wallace commented on the melding of these viewpoints stating that the unexpected synergies emerged from the relationship between our human subjects and our plant subjects. The different interpretations of this rapport, according to the participating body, be it a chef, live performers, or scientists, made clear the possibilities of collaboration across kingdoms. It was also an interesting challenge, sometimes an amusing one. The different language styles needed to communicate with people of different disciplines were very interesting on a human-to-human level.

The idea of multispecies collaborations has become a longstanding one in SciArt practices. However, within these works, many ethical issues are raised concerning consent and the agency of participating bodies. These entanglements are further explored in Our Bio-Tech Planet’s exhibition. For example, in the exhibition, the artist Liang Yujue’s work entitled Green Soup explores these multispecies entanglements. In the work, Yujue employs cyanobacteria as a narrative tool and documents the history of cyanobacteria consumption. This narrative starts from the times of the Aztecs and continues by exploring its projected use as a food source for space travel.

In using another species to frame a primarily human understanding of history and time narratively, Yujue reveals specific motivations, politics, and cultural values, such as the continual human pursuit of increasing our lifespans. The work then offers a moment of critical reflection on the exploitation of cyanobacteria to fulfil human desires and potential visions of the future.

In addition to multispecies dialogues, Our Bio-Tech Planet also offers new interpretations of a more historical concept of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Urpflanze by featuring creative explorations of the chicory plant. Inspired by the botanical diversity of Italy, Goethe conceived the Urpflanze as a concept representing the primal plant from which all higher plants have been derived. The Urpflanze was seen by Goethe as the singular plant form in which all future plant forms already existed inside [1].

The chicory plant has been found to have inspired both the idea of the Urpflanze and the German Romanticized concept of the Blue Flower. Both figures are further interconnected conceptually based on Goethe’s aesthetic descriptions of them.[2] With its bright blue flowers, the chicory plant embodies these romanticized ideals expressed by Goethe, but it still holds contemporary importance as the centralized figure of the CHIC Consortium. The Consortium’s project launched in 2018 to find new plant breeding techniques to improve chicory’s use as a multipurpose crop for high-value consumer products [3].

Artists Anna Dumitriu and Alex May explore the chicory plant’s biotechnological potential considering its historical and cultural entanglements. Their artistic engagements with chicory are representative of what Wallace has stated is one of Art & Science Node’s hopes to achieve with these transdisciplinary collaborations with the CHIC Consortium concerning the topic of the future of plants and humans.

Wallace explains Plant breeding is a historical act, but re-situating this in a lab can make people uncomfortable. A question we ask ourselves at ASN is: does the term “unnatural” even exist? It’s worth noting, however, that the main aim, also for me personally, is to never harm our co-habitants and our earth if we can humanly avoid it.

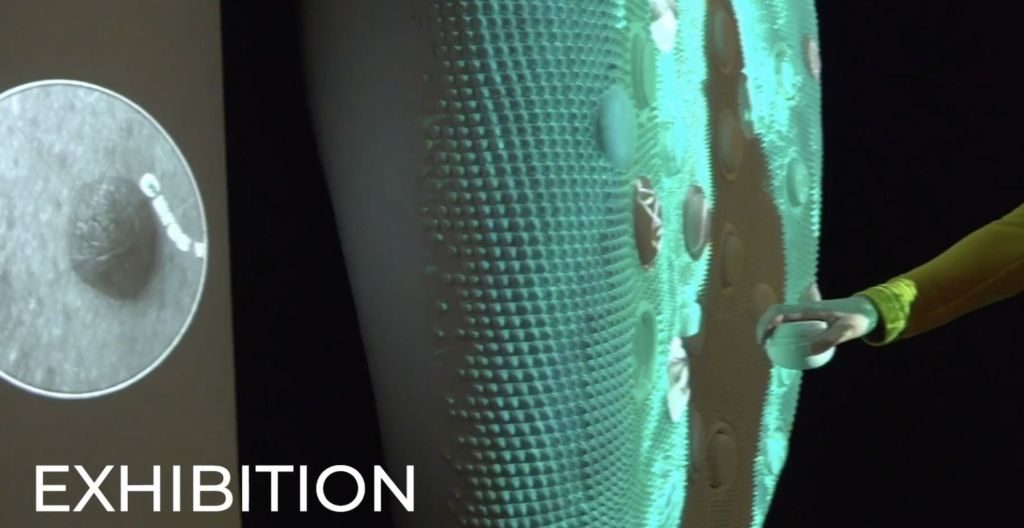

Lastly, artist and professor Dr Jill Scott’s work entitled Aftertaste features an interactive media installation artistically engaging with research on the chicory plant’s flavour, molecular behaviour, and health benefits. The work comprises three sculptural models designed to “biomimic” the sensations of flavours with images that can be experienced alongside sound compositions, film loops, real-time sonification, and recorded testimonies.

When reflecting on these works and their subject matter’s historical and cultural connotations that are deeply embedded into the figure of the “Urpflanze”, a question emerges about the nature of human and plant relationships and how this will continue to develop in the future.

As seen deeply embedded into the CHIC Consortium’s mission, agriculture and uses in agriculture tend to play a predominant role in dictating how plants are culturally valued. This predominance of agricultural influence on human and plant relations extends beyond the act of human hands intervening with and rebuilding genomes. It is also deeply embedded in how we select plants for preservation and conservation measures.

As a preparation measure against a potential ecological catastrophe, the Norwegian government, the Nordic Genetic Resource Center, and the Global Crop Diversity Trust have created the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on the island of Spitsbergen in the Artic Svalbard archipelago. However, in this Global Seed Vault, there are 1,165,041 seed varieties currently being stored to safeguard plant biodiversity as a measure to protect the future of human food supplies.[4] This excludes other plants with ecological value or other cultural value outside of agriculture.

This absence of non-agricultural plants in our current doomsday preparations is felt deeply in Jadwiga Subczyńska’s Marsquakes, which speculates about potential life on mars. Set in a vision of the future without diverse flora, the work explores how digital plants could fulfil this human need. The scarcity of botanical diversity is also pervasive in Tuana Inhan’s House Humans. The video and karaoke installation speculate on the fetishization of house plants as a human coping mechanism to deal with a world where the consequences of our social, environmental, and global crises persist.

These shifts in perspective are at the core of Our Bio-Tech Planet‘s investigations, as the program sets out to critically examine the relationship between humans and plants. This is something that Wallace has found most interesting in the curation of the exhibition stating, “Have you ever considered that, rather than grass being used for decoration and comfort by humans, that grass uses humans as a seed dissemination tactic to spread their presence across the globe? Other plants do this in the same way. Shifting our perspective creates endless possibilities…”

It is hard to tell what kind of future will emerge from these endless possibilities. However, the creativity emerging from Our Bio-Tech Planet asks us to both reflect on our all-too-human motivations and grow toward creating a vision of the future that explores what a more-than-human kinship could be.