Text by Annique Cockerill

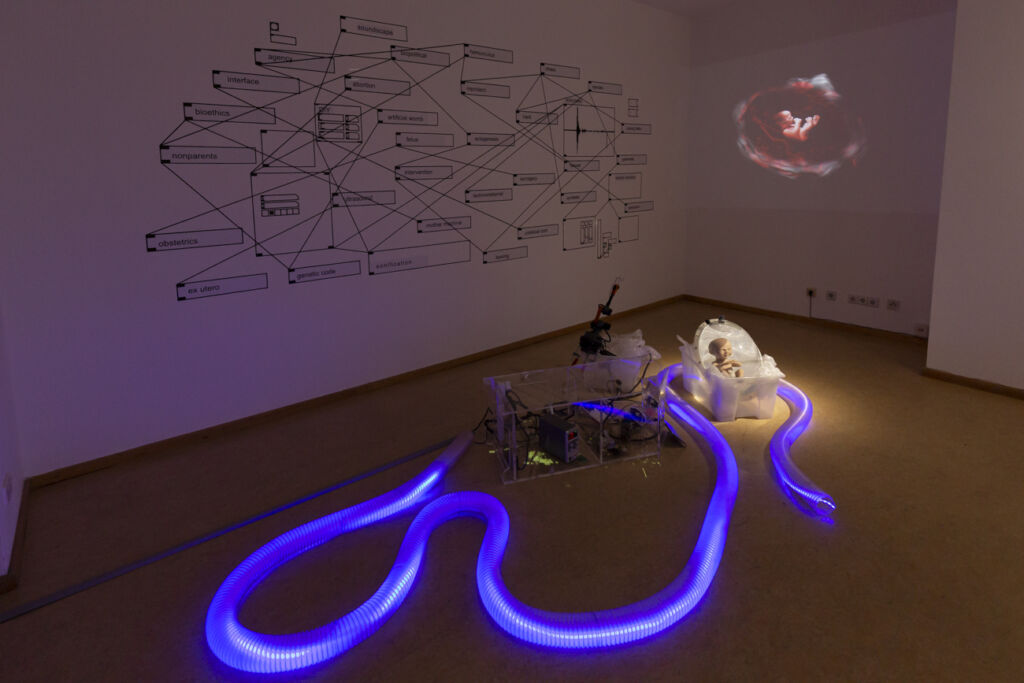

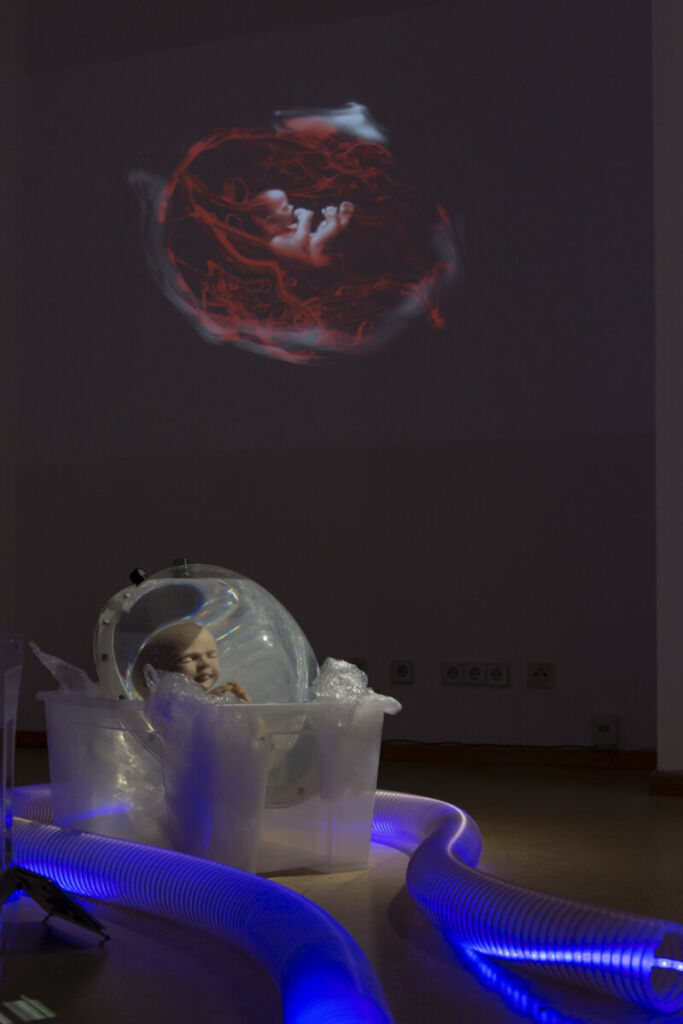

You can see the foetus curled up in its perspex womb from the street outside Art Laboratory Berlin. It rests amongst wires and robot parts. From the middle of this science fiction nest, you can hear a warped noise that sounds too organic to be fully machine, too synthetic to be natural. In a quiet moment, artist Shu Lea Cheang seems to listen to the techno-drone for a moment, before smiling at me.

Sounds just like a woman’s labour.

Art Laboratory Berlin’s newest exhibition, Matter of Flux, brings together three projects that delve into the relationship between medical research as an apparently objective practice and the experiences of female and non-binary bodies within the healthcare technology paradigm. The exhibition includes installations from artists Lyndsey Walsh, WhiteFeather Hunter, Shu Lea Cheang and Ewen Chardronnet, culminating in a space that critically reflects on nature, gender, and health. Each project is also accompanied by artistic research, which has informed the development of the works.

Shu Lea Cheang and Ewen Chardronnet collaborate in the project UNBORN0x9, a mixed media installation that imagines a future where a foetus can develop outside the female body (ectogenesis). The project explores the role of obstetric science in the increasingly technical experience of human reproduction and extends this experience to a futuristic conclusion of ectogenesis.

Medical advancements surrounding maternity care, such as the development of ultrasound, raise questions about the penetrative gaze on (and into) the pregnant body. The robotic parts of the installation is a low-cost echo-stethoscope that is being developed by echOpen Fablab, who invited Cheang to hack the product as part of a collaboration piece. The result is the audio component, the “woman’s labour”, which is the sound of an ultrasound that has been converted into sonic output instead of visual.

The window view of UNBORN0x9 leans into the feeling of “looking in” that the ultrasound provides. Pregnancy almost always results in some loss of autonomy for the person carrying the child. In this case, the cultural expectations for pregnant people to display images of intimate organs (their womb) is unlike almost any other medical scan.

The artist harnesses xenofeminist criticism of naturalism to disrupt this falsely sanitised gaze into the female body. In the work feeling so surreal, it becomes apparent how unfamiliar that disconnect is currently, and therefore invites the viewer to recognise their own wilful disregard of mother as an autonomous being during the pregnancy process. The cultural disconnect births ideas around how social concepts of gender, motherhood, and justice might exist in our current medical paradigm and how the limits of what is “natural” are arbitrary in a system driven by technological advances.

Experimenting with menstrual liquid for tissue culture, WhiteFeather Hunter continues exploring dissonance between scientist and subject in the context of gendered medical research in her PhD project The Witch in the Lab Coat. The function of menstrual fluid for stem cell research is a promising field, with cells isolated from menstrual blood providing some of the best samples for tissue growth. However, the field continues to be stunted by cultural taboos around period blood.

The custom-made bioreactor at the centre of the installation contains a live tissue culture isolated from WhiteFeather’s own body, growing in organ-like vials. This experiment is a sort of performance art: the growth of the cells themselves, but also the ethics and hygiene procedures required to work with human tissue that alienate them from the subject. As a PhD candidate, WhiteFeather has to sign over ownership of the cells to her supervisor, and they must be treated as biohazardous materials. She explores the dissonance of working in laboratory sterility whilst the subject of her research is a taboo product of herself.

The project also contrasts modern science and witchcraft, highlighting the taboos that are still embedded in the supposedly “objective” medical research field. The aesthetics of the lab are borrowed through glassware, Petri-dishes, and her lab coat but exist as subversions of their laboratory equivalents. The glass bioreactor chamber that contains the growing cells is custom blown and pumps the nutrient liquid needed for cell growth through organic-looking endometrial chambers. Petri-dishes containing abstracted models of human tissue and made from the bases of glass jars.

These recycled elements connect the historical use of menstrual blood in witchcraft practices, supported further by sigils painted in red ochre. A lab coat hangs on the far side of the room, embroidered with the machine used to remove menstrual samples hygienically. It’s stained with the artist’s blood, the “unclean” menstrual fluid that has not gone through clinical processes that render it acceptable for use.

In the room next door, a different kind of cell line is incubating. Lyndsey Walsh’s project Self Care responds to the artist’s own experience with an inherited gene mutation. Lyndsey was 18 when they were diagnosed with the same BRCA1 genetic mutation that caused their mother’s breast cancer. Self Care reconciles the weight of predetermined and the identities of caretakers and inhabitants of a body they’ve been promised will betray them. The result is an intimate multimedia exploration of breast cancer, gender, motherhood, and the weight of knowledge.

Two screens play audio in tandem, accompanied by visuals from historical breast cancer PSA’s, seeped in an uncanny anachronism. The first is an interview with the artist’s mother by the artist themselves, walking through the shared experience of mother and child as their status as patient intersect. Together they explore similarities in their circumstances and unpick the tense differences that set them apart. The dialogue between generation grounds Walsh’s work in the intimate experiences that connect them and the medical horrors that isolate them.

The second audio is a letter Walsh wrote to their mother about the diagnosis, reflecting on their relationship and how cancer has altered it. By contrasting the back-and-forth of the interview and this one-sided letter, the artist manages to capture the feeling of a private confession. The subject develops past cancer itself and into lessons passed on about identity and the construction of the self in the eyes of others. This ties into surgery and reconstruction topics, either after cancer or as a preventative measure.

All of this supports the main subject of research: a device that imagines taking on the caring responsibility of one’s own cancer, even after it has been removed from the body. Hanging in what the artist affectionately calls their closet, Walsh has constructed a binder that allows its wearer to grow and feed living breast cancer tissue. When worn, it nests the tissue close to the chest from which it has been removed. In doing so, Walsh challenges the externalisation of cancer as a bodily enemy and incorporates the cancer into a transformed identity that is an extension of the self. The symbol of the binder as a mechanism of gender disruption introduces questions of transgender health experiences in a highly gendered diagnosis.

The works in Matter of Flux delve into questions surrounding ethics and medical research, particularly in the context of gender and the experience of female-assigned bodies. The exhibition is curated by Regine Rapp, Christian de Lutz, and Tuçe Erel and is accompanied by a four-day festival of the same name, commencing on June 15. The festival includes workshops, performances, panel discussions, and reading groups, with over 40 international Berlin-based artists and scholars collaborating to further extend the exhibition’s themes.