Text by Caterina Avataneo

Scorpio season has knocked once again, boosting Halloweenish taste for velvet, candlelight, and gloom. As per tradition, bookshops go goth, stacking their windows with special editions of Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley, while pâtisseries stage their own miniature danse macabre with pumpkin desserts and spun-sugar cobwebs. Despite its obsession with death, among others, the Gothic has never fully died out. Its recurrences in history are well known, and have invested contemporary art as well. Yet under advanced capitalism, the rhythm of its returns has exponentially accelerated, stripped into a hollow simulacrum of plastic bats. Can the Gothic still be relevant today?

The Gothic has retained both popularity and critics’ scepticism throughout its multiple historical iterations. Its flirtation with the mainstream in its current form arguably began in the 80s, when the same deregulation policies that expanded global capitalism also created a market for commodified gloom. As Lauren Goodlad and Michael Bibby note in Goth: Undead Subculture (2007), “goth” became a recognisable niche, and an exportable mood of profitable melancholy. From Siouxsie and the Banshees to New Order, eyeliner turned manifesto and sadness into social capital. The industry learned how to package outsider aesthetics into consumable trends that trickled into the following decade.

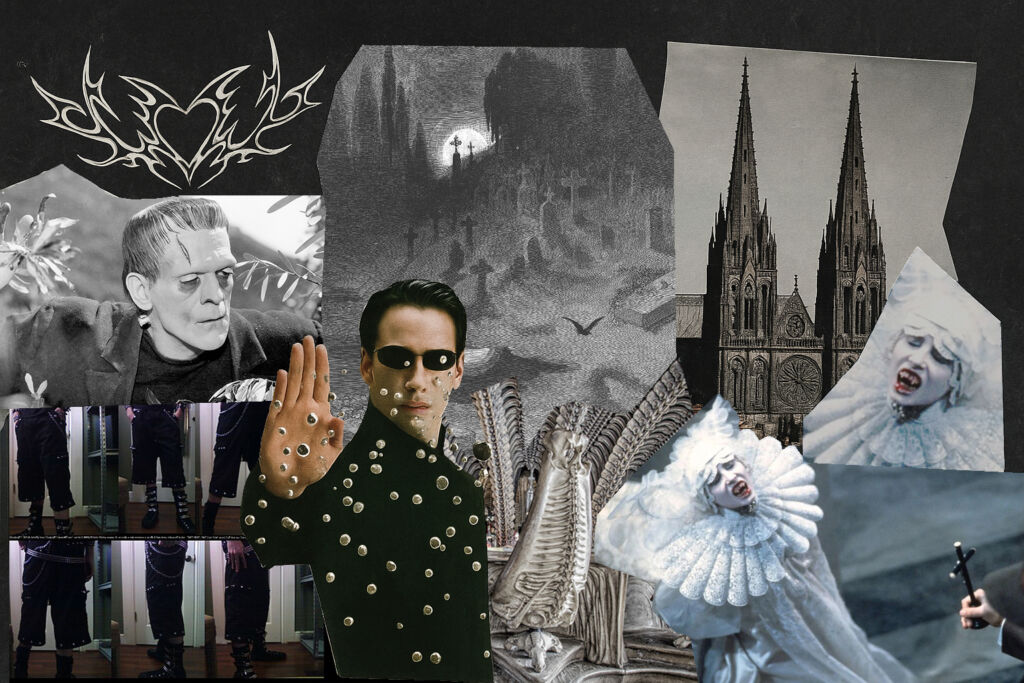

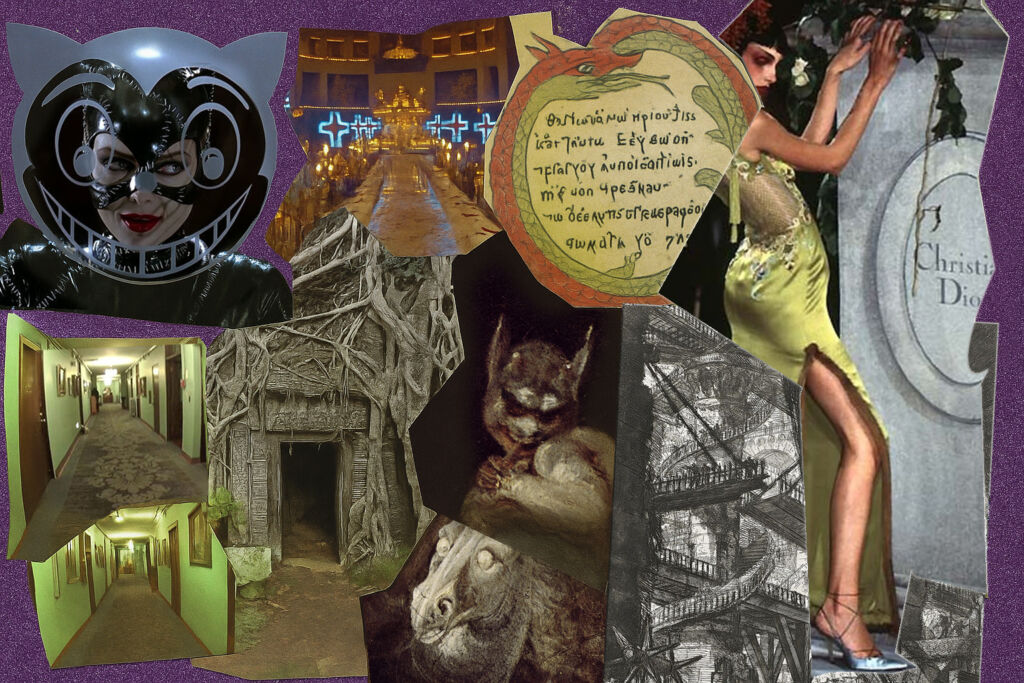

By then, catwalks got crowded with corseted lace and blood-red silk with crucifixes and chokers spanning Victorian fantasy and funereal minimalism. Think Alexander McQueen, John Galliano or Rick Owens at the time! Progressively, the goth scene’s repertoire was made easy to trade. Gender play and androgynous styling lost their subcultural expression, yet remained marginal. The goth’s way of making the everyday seem unsafe turned into Buffy’s era, forgetting on the way the cultural experimentation born out of Thatcherian conservatism, and relegating goth atmospheres to a teen drama that promoted normalcy more than one would guess.

But to stop at the aesthetic traits of gloom would miss the point entirely. John Ruskin was among the first to make this explicit in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), describing “Gothicness” not as a style or a set of visible features, but as the expression of a particular mental condition. Each Gothic cathedral, he writes, is a combination of inner tendencies: imagination, love of variety, delight in imperfection, and material and formal experimentation. In this sense, I believe the Gothic is less about darkness than about vitality, yet undeniably bound with the depth of any psychological terrain—thus carrying darkness within. It’s not because of their settings that Gothic novels such as Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) are today’s classics, but for the way they confront the human psyche.

As Linda Bayer-Berenbaum observes in The Gothic Imagination (1982), the Gothic novel was an expression of some of the most exciting and disturbing aspects of modern existence. Beneath haunted castles, misty forests and romantic nostalgia for times gone by, lies the essence of the Gothic orientation: a persistent need to confront what society tends to deny. Far from being restricted to a single time or culture, Gothicism is an enduring sensibility, capable of mutating across centuries. From medieval cathedrals to sickly-skin fashion, Victorian ghost stories or The Matrix, the Gothic returns whenever the human imagination is compelled to face its own shadows.

It’s undeniable that the Gothic is bound to collective psychological undercurrents. Its recurring fascination with fear, taboo, and the unspeakable mirrors the anxieties of the societies that produce it. This is probably also why it’s often dismissed as unsophisticated—because it explores what is meant to be repressed, precisely embracing its grotesqueness. Death, decay, desire, excess: the Gothic gives form to what reason cannot easily metabolise. It makes perfect sense that many theorists have registered a Gothic sensibility resurfacing when the rational order begins to crack, haunting whatever form of socially accepted norm begins to falter, thriving in moments of cultural instability and social change. Every recurrence of the Gothic marks a point of confrontation with evil and a curiosity towards transformation, which brings fear within. Its themes are thus both universal and historically specific.

In the Middle Ages, for instance, Gothic cathedrals coincided with a transformation in the notion of faith. Their soaring height and improbable lightness, seemingly defying gravity, made the sacred tangible. God was no longer only mediated by enlightened men of faith, but refracted through coloured glass and available to anyone who dared to look up. The Church’s monopoly over the divine was decentralised, opening space for more personal forms of belief and superstition, at a time when the Great Plague had deepened humanity’s confrontation with fear.

Centuries later, the Gothic novel would originate out of a different kind of upheaval. Industrialisation brought social change that unsettled the structure of the family, among other institutions. As different theories of creation, medicine and psychiatry entered the cultural imagination, the great Gothic characters of the century —Frankenstein (1818), Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886)— arose from faith giving way to technological experimentation with consciousness. In the 80s, instead, Gothic sensibility found fertile ground amid socioeconomic decline and the AIDS crisis, in a climate where urban decay was met with a rise in moral conservatism. The goth scene responded to the anxieties of a culture policing gender, sexuality, and the lower class.

In contemporary art, the Gothic gained particular traction in the 90s. Gilda Williams noted on multiple occasions —her MIT anthology The Gothic (2007); Gothic v. Gothick: On the Uncanny’s Campy Cousin (2009)— how visual artists progressively started use Gothic tropes such as haunted locations (Gregor Schneider, Jane & Louise Wilson), labyrinths and prisons (Mike Nelson), ruins (Robert Smithson, Tacita Dean), monsters (Paul McCarthy), family secrets (Louise Bourgeois) and so on. She employed Fred Botting’s term “candygothic” to distinguish between genuinely unsettling depictions of the modern human condition and medieval-flavoured, marketable outputs.

On that note, I love how Catherine Spooner reminds us in Undead Fashion (2007) that if you are a real vampire, you don’t need to dress like one. Interestingly, she also argues in Contemporary Gothic (2006) that the contemporary artworks permeated by a Gothic character have been more obsessed with bodies than in any of its previous phases; likely a counter-reaction to the disembodiment of a digital society under late capitalism. Think of Jake & Dinos Chapman and their grotesque anatomies.

The reason why I started looking into Gothic’s recurrence is that, since the mid-2010s, I too, began noting a revival within more recent contemporary art. After publishing his book This Young Monster (2017) on the nature of freakishness, Charlie Fox curated a two-chapter group show, one of which was at Sadie Coles, London, in 2019 under the title My Head is a Haunted House. The show took the mist off the haunted house as a metaphor for interiority, literally proposing a curatorial inner self-portrait, and an homage to the history of horror through the works of artists such as Alex Da Corte, Marianna Simnett, Mike Kelley and Robert Gober, just to name a few. I appreciated the honesty of this show, and above all, its vitality—even if at times it resulted more camp than spooky.

Meanwhile, Digital Gothic at CAC La Synagogue de Delme (2019) traced a historical continuity of sombre imagination and dark romanticism, exploring the effect of digital technologies and the internet’s increasing pervasiveness in the life of the global population. The unease of this show came from a temporal displacement of the Gothic, no longer looking back at the ruins of history and unfolding instead within the constant now of digital circulation. A haunted archive turned live stream, thriving on overproduction of images. A year later, Ghosthouse at Den Frie, Copenhagen (2020), only run at night, transforming the art centre into a haunted house of spectacle.

The 59th Venice Biennale, The Milk of Dreams (2022), was also quite Gothic, although not overtly defined as such. By asking what constitutes life, the biennial positioned metamorphosis, hybridity, and otherness at the core of global art discourse, showcasing artists such as Andra Ursuta, Marguerite Humeau, Marianne Vitale, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, or Mire Lee, just to name a few pertinent examples. That exhibition, I believe, was Gothic precisely because it explored contradictory relations between past and present, human and non-human, conscious and machinic. And if its inspiration lay in Leonora Carrington’s surrealist reveries, what surfaced in many of the exhibited contemporary artworks was a curiosity towards ambiguity, and the unease of horror. After all, as Anne Williams argues in Art of Darkness (1995), Freud is the Gothic writer of the 20th century. The list could go on—you only need to scroll through TZVETNIK’s Instagram archive, which, between 2016 and 2023, documented a horde of Gothic-driven/abusing shows.

The more I delve into the Gothic, the more firmly I believe that while trashy campiness and romantic gloom are indeed fully embedded in how we view “Gothicness,” the real challenge lies in avoiding memetic outcomes that simply re-enact a Gothic of the past. If the hauntological condition that Mark Fisher describes in Ghosts of My Life (2014) speaks of a culture paralysed by decaying yet undead late capitalism, it would be wrong to locate the Gothic into the doomed immobilisation of eternal returns, though this may well be one of our contemporary anxieties. I find the essence of the Gothic rather moving in the opposite direction, or at least embracing a temporal ambiguity of past and future that keeps the vital potential of transformation alive even if fearful. Anne Williams writes that Science Fiction is Gothic’s daughter because of its structural concern with transgressing boundaries, the monstrous, and the unknown.

I realised it’s impossible to try to discern the Gothic in its infinite declinations, especially as in contemporary art, which is my field of analysis, nobody would self-define as “Gothic”. Already, Ruskin wrote that while many have some notion of the meaning of the term Gothic, to truly define it is an improbable task. I am thus invested in witnessing how it can manifest today, as its dark imagery shifts settings, while continuing to explore universal inner contradictions and societal anxieties. In the face of extractive economies and mine-farming, climate change and the irreversible processes of the Anthropocene, algorithmic networks and identity politics, monsters too are destined to be re-imagined.

If AI is already having an impact on a certain kind of garbage Gothic, its excess is probably hiding a revolution of the weird yet to be fully comprehended. Ruskin’s six characters of the Gothic remain an essential guide when attempting to make sense of this sensibility: savageness and rudeness, love of change, love of nature, grotesqueness and disturbed imagination, experimentation, redundancy and excess. The Gothic is an ontological condition, an expression of the darkness within. An encounter with what terrifies us, so that we might see through it. Yup, you guessed it: I have Scorpio placements, and I am awfully excited about this all.