Text by Daniela Silva

There is a quiet clarity in the way Eric-Paul Riege, a Diné/Navajo artist, approaches material. Before anything becomes art, before it hangs, drapes, accumulates, or moves, he listens. The artist, whose practice expands through weaving, sculpture, sound, video, and performance, often says that materials have their own agency. They reveal themselves slowly, if you let them. This idea of objects as living beings carries through ojo| |ólǫ́, his expansive institutional exhibition presented jointly by The Bell Gallery at Brown University and the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington. At its heart, the exhibition becomes an encounter not only with Riege’s multilayered practice but also with the long arcs of Diné knowledge, cultural dispossession, and the systems of display that influence what we are allowed or encouraged to see.

Born in Na’nízhoozhí (Gallup, New Mexico) and coming from a family of weavers, Riege is deeply aware of the worlds that textiles carry with them. For him, weaving is not only a technical skill but a form of memory, a way of existing with others, both human and non-human. His work for ojo| |ólǫ́, developed through close study of Navajo collections at Brown’s Haffenreffer Museum and UW’s Burke Museum, becomes an active dialogue with ancestral objects and the environments in which they now rest.

Today’s renewed institutional attention to textile and fibre practices provides a useful frame for understanding the distinctiveness of Riege’s approach. While the Fibre Art Movement of the 1960s–80s brought weaving into sculptural and architectural territories, and contemporary artists such as Cecilia Vicuña or Tanya Aguiñiga explore fibre through ritual or political memory, Riege’s work moves differently. Rather than extending the formal breakthroughs of fibre art, he returns to a Navajo weaving tradition grounded in hózhó, balance, beauty, and relationality, engaging weaving not as an aesthetic revival but as a living system of kinship. In this context, the broader resurgence of textile art becomes a backdrop against which his practice asserts its own cultural, spiritual, and structural specificity.

The exhibition’s title is essential to understanding his approach. ojo| |ólǫ́ divides into two conceptual “beads”: a Diné verb that speaks to existence, shifting from meanings like “eyes exist” or “sight exists” toward the possibility of declaring “I exist.” Replacing the H with the placeholder | | opens a space of questioning. It asks who or what is being seen, and who claims the act of seeing. Riege often thinks about Indigenous objects that once lived in worlds of use, kinship, and ceremony but now sit behind glass, in drawers, or at a careful distance in museums. What does it mean to face objects that may still be alive, resting or waiting? How do we witness them without assuming their stories?

The artist’s practice sits inside these tensions, not to oppose but to converse. He sees authenticity as something dynamic, shaped both by what is shared and what is kept close. The long-standing colonial urge to define “real” Indigeneity, often cemented by museum displays, becomes a space of exploration for him. He finds energy in the gestures of adorning, masking, and concealing, the subtle rhythms of what is offered to a viewer and what remains within the community. In this sense, his work does not invent new scripts of cultural identity but listens to those already present, whispered through fibres, inherited tools, and the movements of the body.

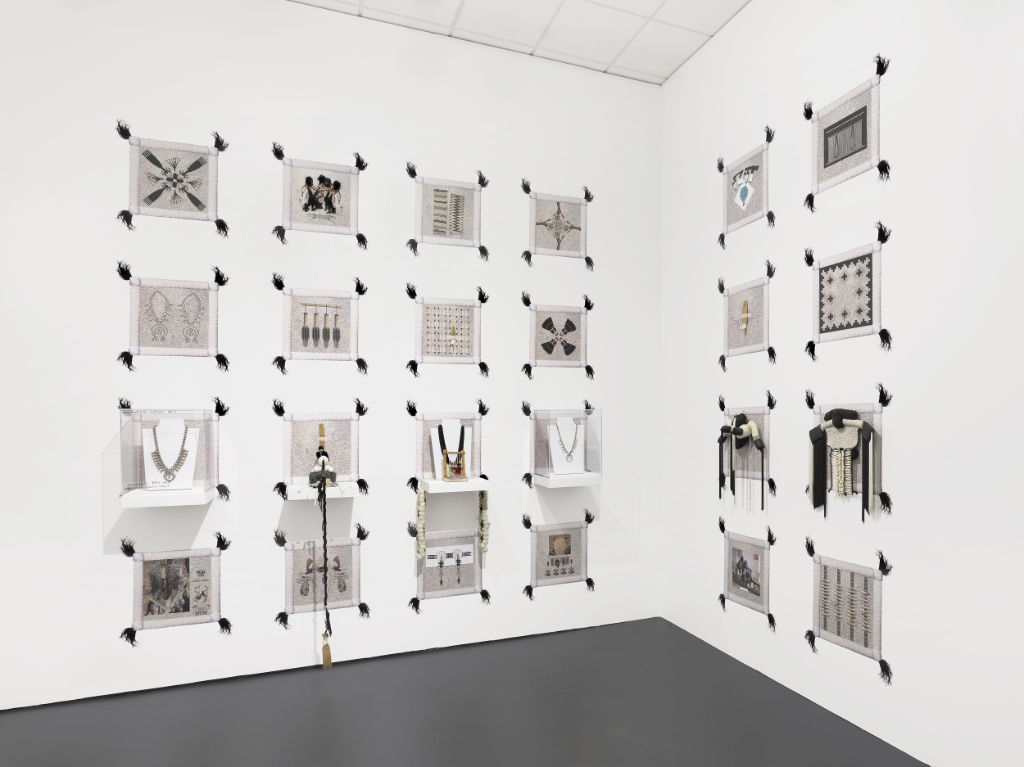

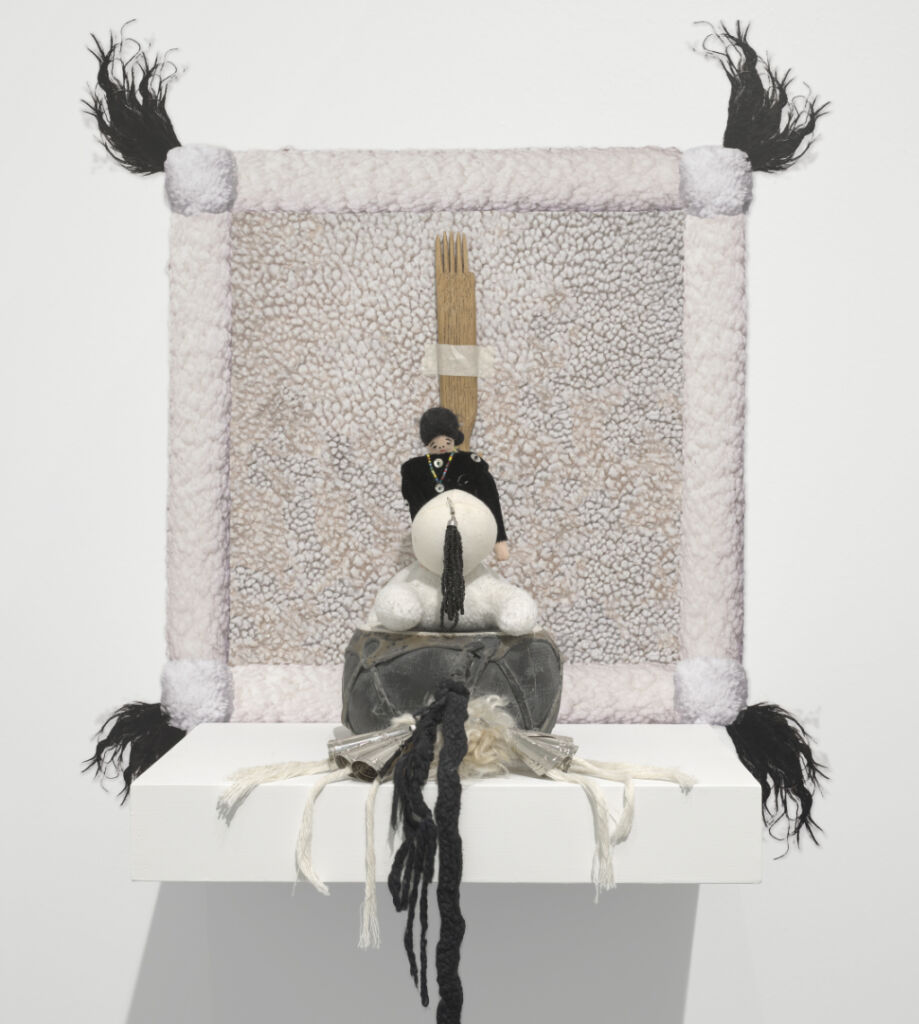

This listening becomes visible in the exhibition’s sculptural works. Riege’s research into historic weavings, combs, jewellery, and tourist market dolls does not lead him toward replication but toward expansion. He takes patterns, construction methods, and hybrid symbols, objects that mix Christian and Native imagery or bear traces of economic history, and transforms them into large-scale, modular sculptures. These pieces resist conclusiveness. They are intentionally imperfect, slightly unruly forms that respect the archive while gently pushing against its authority. Through their scale and softness, they challenge the colonial desire for stability and certainty, insisting instead on cultural continuity as a living, shifting process.

For the artist, materials themselves travel. He often describes the long history held inside something as simple as yarn: a material shaped by many hands before it ever touches his own. His works carry the marks of these accumulated histories, and he welcomes the ways audience presence might continue that journey. In the art world, preciousness often comes from distance and restriction. Riege sees preciousness in signs of life, in change, in wear. Like human bodies, his sculptures show folds, softness, scars, and memories. They are not fixed but temporary, holding the past, present, and future at once.

Performance is equally central to Riege’s practice, though he does not treat it as separate from his objects. He calls his performances “weaving dances,” extensions of his sculptural process and ways of understanding how bodies, his own and those around him, move together. The performances reveal how each object behaves differently, how some pieces demand closeness while others wait in stillness. He does not feel alone when he performs. The sculptures, the setting, and unseen partners around him become part of the movement. This understanding stretches beyond the stage, suggesting that moving through the world or through an institution is itself a weaving practice.

At The Bell and later at the Henry, these weaving dances take on a deeper resonance. The university’s anthropological collections create a charged space, full of questions about cultural visibility, objecthood, and agency. Riege engages these questions with a gentle but direct presence. His performances highlight the risks and responsibilities of exhibiting Native art within institutions shaped by histories of removal. He reflects on what it means to choose visibility when visibility can also be dangerous, especially for Indigenous artists navigating dominant narratives. Refusal, concealment, and play appear as strategies for protecting one’s cultural autonomy.

This care extends to how he thinks about display. Riege sees both authenticity and inauthenticity as important. He wonders what lies between different forms of exhibition. Who decides how objects should be cared for? What counts as proper preservation? A glass bonnet? A brush and hairspray? Planned imperfections? His questions invite us to rethink how we relate to objects, how we hold them, and how holding can be one of the kindest actions. He often compares the loom to a cradleboard, a form of carrying that guides the weaving toward itself. In this sense, care is not distant or sterile but close, physical, and shared.

A printed volume designed by Luminosity Labs will be released alongside the exhibition, featuring essays, images, and contributions from Riege’s collaborators. It reflects his belief that artworks exist within networks of relations. No single voice, object, or institution carries the whole story. Meaning emerges across people, materials, and the many histories they share.

The exhibition arrives at a time when museums are rethinking their own pasts. Yet his work does not settle neatly into narratives of critique or restitution. Instead, it offers a more subtle path: one that recognises harm, celebrates resilience, and centres the ongoing presence of Indigenous knowledge without turning it into spectacle. His textiles, performances, and sculptures do not copy archival objects; they listen to them, respond to them, and move beyond them. In this way, ojo| |ólǫ́ is a meeting place where existence, human, material, and ancestral, takes shape through connection. To stand before Riege’s work is to remember that art, like weaving, is a process of tending, carrying, and allowing things to grow into what they already know how to be. In ojo| |ólǫ́, existence is not declared. It is shared.