Interview by Allan Gardner

Dan Holdsworth is an artist of many accolades, one of the youngest ever to be acquired by Tate’s permanent collection and someone who is dedicated to mapping and representing the changing relationship between humanity and the natural environment. Working in the lineage of naturalist painters like John Ruskin, Holdsworth allows the isolated spaces with natural landscapes to become pictographic communications through his use of traditional observation and modern technological techniques, amalgamating the two to produce visually arresting works mapping our impact on rapidly changing landscapes.

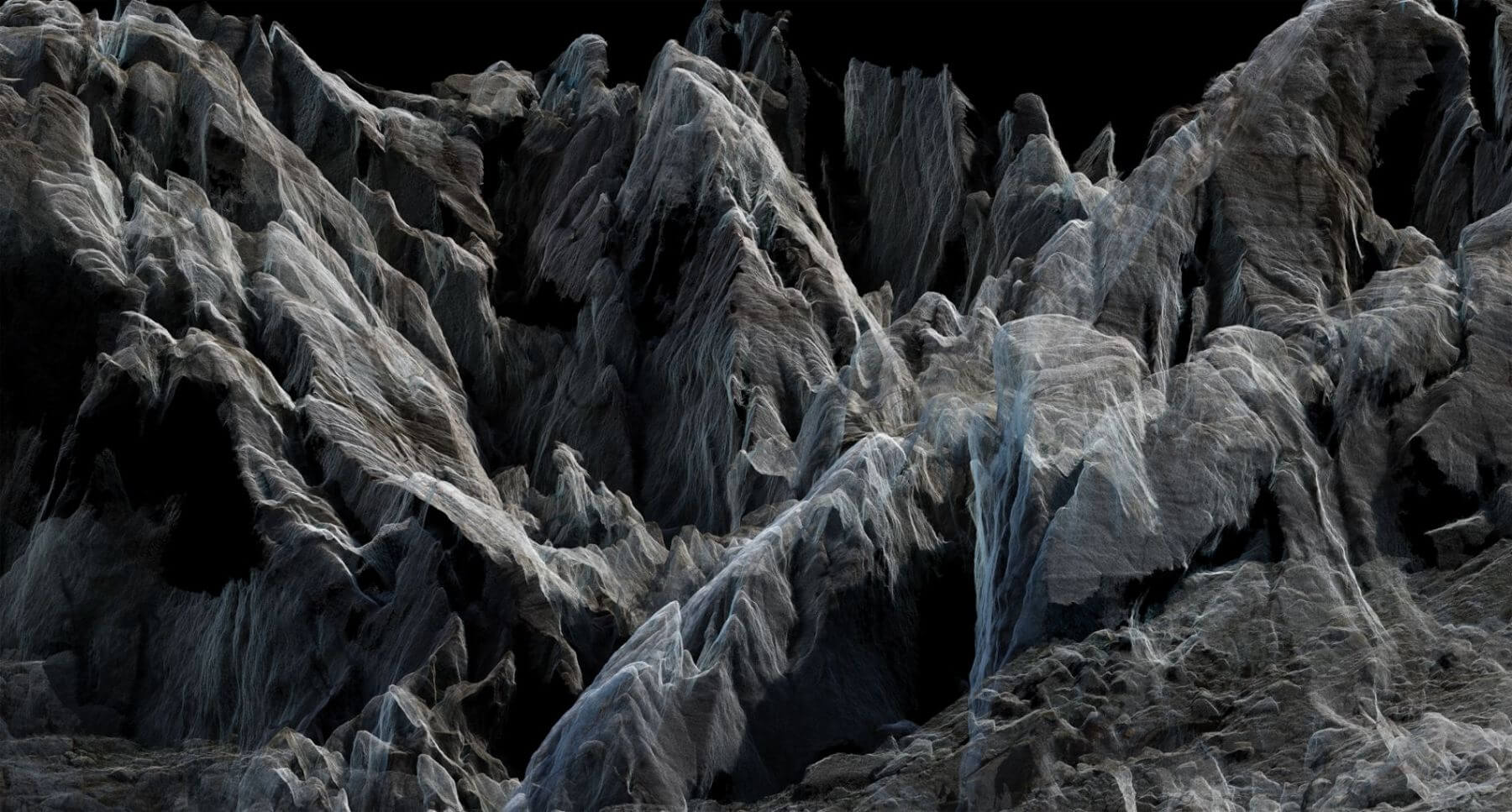

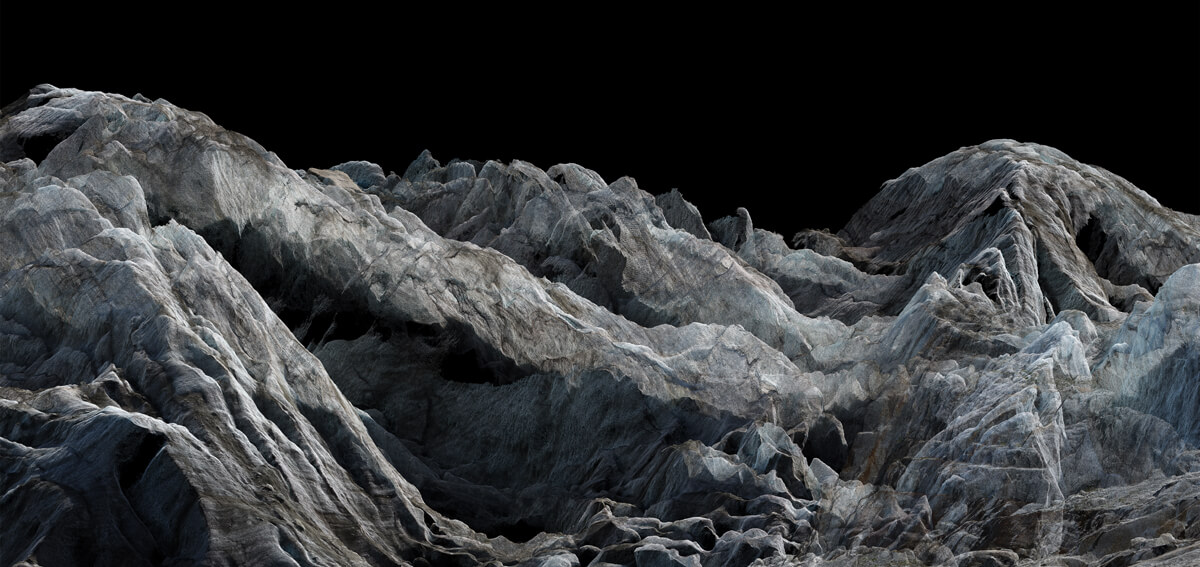

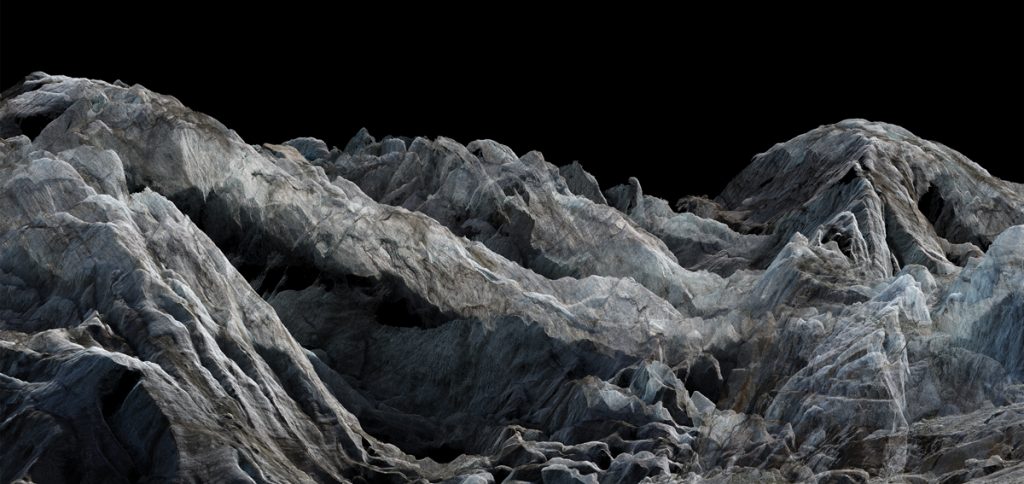

In Continuous Topography (the first in a series of two solo shows being held in series at the Northern Gallery of Contemporary Art in Sunderland), Holdsworth utilises technology ranging from specialist camera equipment and drones to lasers and software produced for use by the military and climate scientists. Through pushing the technological limits of representation, Continuous Topography provides a representation of the cost of our own existence on the environment, as the series of images expose the rapidly changing alpine landscape.

By working with frontier technologies, Dan Holdsworth pre-empts the ubiquity of scientific tools within an art context. Using these methods, he is able to create works which provide new insights into the human relationship with the natural environment as well as our perception of our environments as we interact with them.

In Holdsworth’s 2012 photography project entitled Mirrors, this sort of environmental interaction was explored through the layering of different means of perception. When interacting directly in an environment, taking a topographical reading of an environment and also photographing that environment, disagreements occur. As these environments change, our re-perceiving them becomes impossible.

To my mind, Holdsworth’s work provides a sort of diaristic representation of human interaction with the natural environment from several perspectives. His presence within this environment, both as a space to make artwork or conduct research and as a sort of social space, interacting on a personal level by walking the hills, being physically there in relation to them. It provides the work with a sort of personality that can be lacking in environmentally focused research works, but this is not the case with Dan Holdsworth.

Drawing comparison once more to old masters, like Turner depicting the waves, Holdsworth looks out upon the landscape and draws inspiration. The split in intention comes at the point in which, historically, artists took inspiration from the natural world without giving anything back, and this is not the case with Holdsworth. His works also read as a warning, creating arresting visual motifs to represent our environmental impact. Without being completely explicit, the works force us to consider our personal impact, carelessness, and what we can do to prevent this rapid deterioration.

For those that are not familiar with your work, could you tell us a little bit about your background and the aims behind your practice exploring the nature of the landscape and the nature of photography?

I can best describe the overall trajectory of my work overall in terms of how my working processes have changed and, in particular, how the subjects in my work have become the very processes by which it is made. The origins of my approach to photography lie in the fact that I grew up living alongside an industrial landscape in the north of England – one which was right next to a national park.

From an early age, I saw enormous, powerful chemical and steel works on one side and a nature reservation or ‘wilderness’ right next to us on the other. We lived there because my father was a scientist in one of the chemical works, one of Europe’s largest chemical plants. So I saw science and nature as being adjacent, as it were, rather than as opposed to one another or separable. In my teenage years, long before seeing the Bechers’ work, I became very aware of the magnificence and strangeness of industrial architecture.

The industrial landscape in and around Teesside in North-East England is unique. It inspired Ridley Scott’s scenography in Blade Runner as much as Tokyo did: Scott grew up there as well. So my very earliest work, when I began to use a camera, started with documenting that architecture. My earliest starting points were the ideas of ‘the technological’ and ‘the industrial’. The tension or relationship between the technological and ‘the natural’ still preoccupy me. The related problem of how we, as non-specialists, know ‘science’ and how it is publically depicted became my second source of fascination.

What activities does ‘science’ consist of? How can we imagine and visualize them? Those issues run right through my work. What we call ‘the sciences’ became ‘materials’ to me in the way sculptors use materials. In particular, the kinds of architecture they need or develop became an obsession for me, in the way that the Bechers had looked at ‘heavy industry’. Architecture mediates how we imagine a discipline or a discourse: it provides us with symbols, and images of, in the case of science, how the world is changing and what the future will bring.

Continuous Topography was made over many years in a unique collaboration with a geological research scientist. Could you tell us the intellectual process behind it?

Since 2011 I have been working with Geomorphologists and Geologists at the University of Northumbria to explore the 3D mapping of glacial landscapes and observe the effects of climate change over short timescales. Since then, I have been working to develop the processes they use, which led to me directly supporting PhD student Mark Allan and their research project between 2013 and 2017.

As part of this collaboration, I have been directly involved in developing cutting-edge photogrammetric (photographic) survey techniques and applying these to document glacial change in Europe. Photogrammetric surveys can record what a place is, or was, at a particular point in history, when the climate might be tipping. I was initially interested in this technology for its power of observation. It provided a means of examining the ‘architecture’ of a site in unprecedented detail, with unparalleled ‘objectivity’. I saw that by working with these new techniques, it could be possible to create a new aesthetic language and develop an intimate and dynamic realisation of the Earth’s rapidly retreating glaciers.

What was the biggest challenge you faced for its development, either technical or conceptual?

Working on and around glaciers can be dangerous. The dynamic nature of the glaciers themselves and the fast-changing weather in the mountains means there are always risks to manage. The work evolved over several years, and there were technical challenges along the way, but as with any research, these were very much a part of the natural development of the work.

What has been your experience of this artist-scientist collaboration?

The intersection of art and science is something that I have explored in my work now for nearly two decades. The recent work has been more direct. Collaborating with scientists has enabled me to work with new mapping and imaging tools, but just as important has been the conversations with the scientists I’ve worked with.

In 2011 I didn’t start out on this research with an explicit objective regarding the art I would make. I had some strong ideas and an intense curiosity to explore. I was excited by the possibilities of working with these new materials. I committed to the journey of collaboration, and the work naturally evolved through this process.

In Traverse, a new two-channel work accompanying Continuous Topography, you have digitally composited 600 images taken by a drone. What is your experience of working with this technology?

Working with the latest geo-cartographic innovations, it is possible for hundreds of photographs taken from a helicopter or by a drone to be meticulously compiled and plotted using GPS coordinates. The result is a large-scale ‘mosaic’ image of the landscape, or in this case, Glacier, in unprecedented detail. Traverse realises this level of detail through a series of moving images, which intimately explore these unique and ephemeral forms.

Would you consider your work akin to a contemporary version of Naturalists as John Ruskin and his protégés the Pre-Raphaelites?

Yes, Continuous Topography is directly related to the tradition of artists like John Ruskin and William Turner, who documented Mont Blanc and its glaciers, or Timothy O’Sullivan and Carlton Watkins, who were the first photographers to document glaciers in the American West. The historic trajectory and chain of associations might be thought of as being that Watkins’ and O’Sullivan’s photographic surveys were re-used by the ecology movement to lobby the US Government.

They were instrumental in enacting the first laws to preserve ‘wilderness’. The 19th Century American Geologist Clarence King, who led these surveys and commissioned Watkins and O’Sullivan, was highly influenced by the writing and ideas of Ruskin. Their images were highly emotive and subjective interpretations of a place, which gained political traction by being appropriated for other reasons. I’m interested in how those photographs had their own independent existence in the world as objects, independent of their original purpose. Continuous Topography is a visual representation of what I call “a future archaeology”: we see the world as if from a distant point in time rather than space.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I think I can speak for most UK-based artists when I say that the biggest enemy of creativity is current government policy. With the current regime of cuts to the arts, there is less money in schools for art, less money for public art institutions, and so less funding for artists. Government policy is actively breaking down the ecology that existed in the arts and making the UK a much more challenging environment for artists to live and work in.

You couldn’t live without…

This could be a long list, but if I chose just one thing, maybe I couldn’t live without my walking boots!